A Cure For Writer’s Block in Celan’s Letters

A remarkable correspondence is also incredibly inspirational.

All summer, I have been immersed in reading the great poet Paul Celan’s letters. I wonder if there will ever be another correspondence like this extraordinary exchange. For sixteen years, Celan corresponded with the poet Nelly Sachs, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1966—when she shared it with Shai Agnon, the towering Hebrew fiction writer, who to be totally fair, completely deserved his own unshared prize and turn in the limelight.

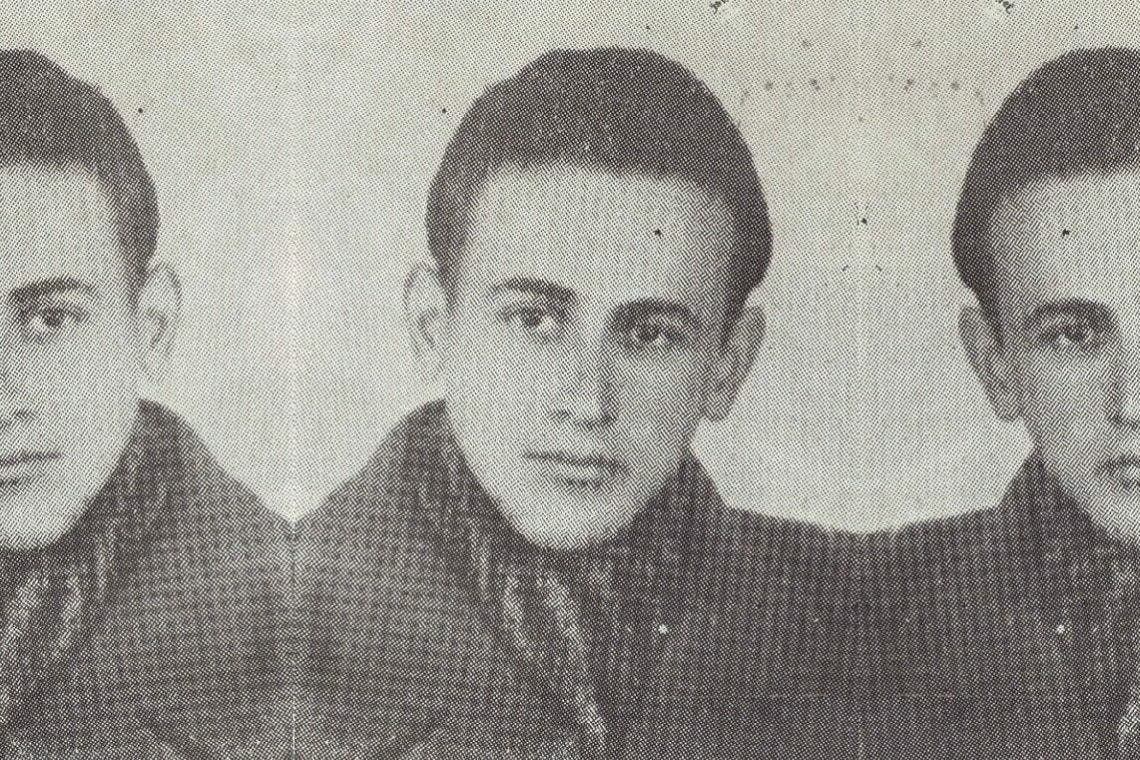

Paul Celan, left, and Nelly Sachs, right.

Both Celan and Sachs were Jewish poets who survived the Holocaust and wrote poetry in German. These letters were how Celan and Sachs kept each other’s faith in poetry, and humanity, going. They have that mesmerizing effect on readers, too.

I want to highlight three individual letters. The first is the first letter in the correspondence—a beautiful note from Nelly Sachs that to my eye captures who Celan is as a poet. The second is Celan reaching out to a struggling Sachs with a way to continue in poetry. And the third is Celan documenting his anger at the continuing hatred he experiences, years after the war.

Who These Letters Are For

I believe the letters are not just for poetry readers, or for writers looking for a cure for writer’s block—though Celan’s solution is the most creative cure I have ever encountered—but for everyone interested in the history of the 20th century and its deep effects.

Paul Celan Nelly Sachs: Correspondence, with an introduction by John Felstiner, translated by Christopher Clark and edited by Barbara Wiedemann. (Sheep Meadow Press, 1995) brings all the letters together—both sides of the correspondence—for the first time. The originals are now at the Literaturarchiv in Marbach (Sachs) and in the Royal Library, Stockholm (Celan).

The letters capture the loneliness and bravery of the decision to continue to write in German. “Only one thing remained reachable, close and secure amid all losses: language,” Celan once said. Both poets kept writing German poems while living outside Germany—Sachs in Stockholm, and Celan in Paris. They were each forever exiled from their childhood homes and countries, but not from their mother tongue.

Both Celan and Sachs saved the other’s letters; Celan even saved the envelopes.

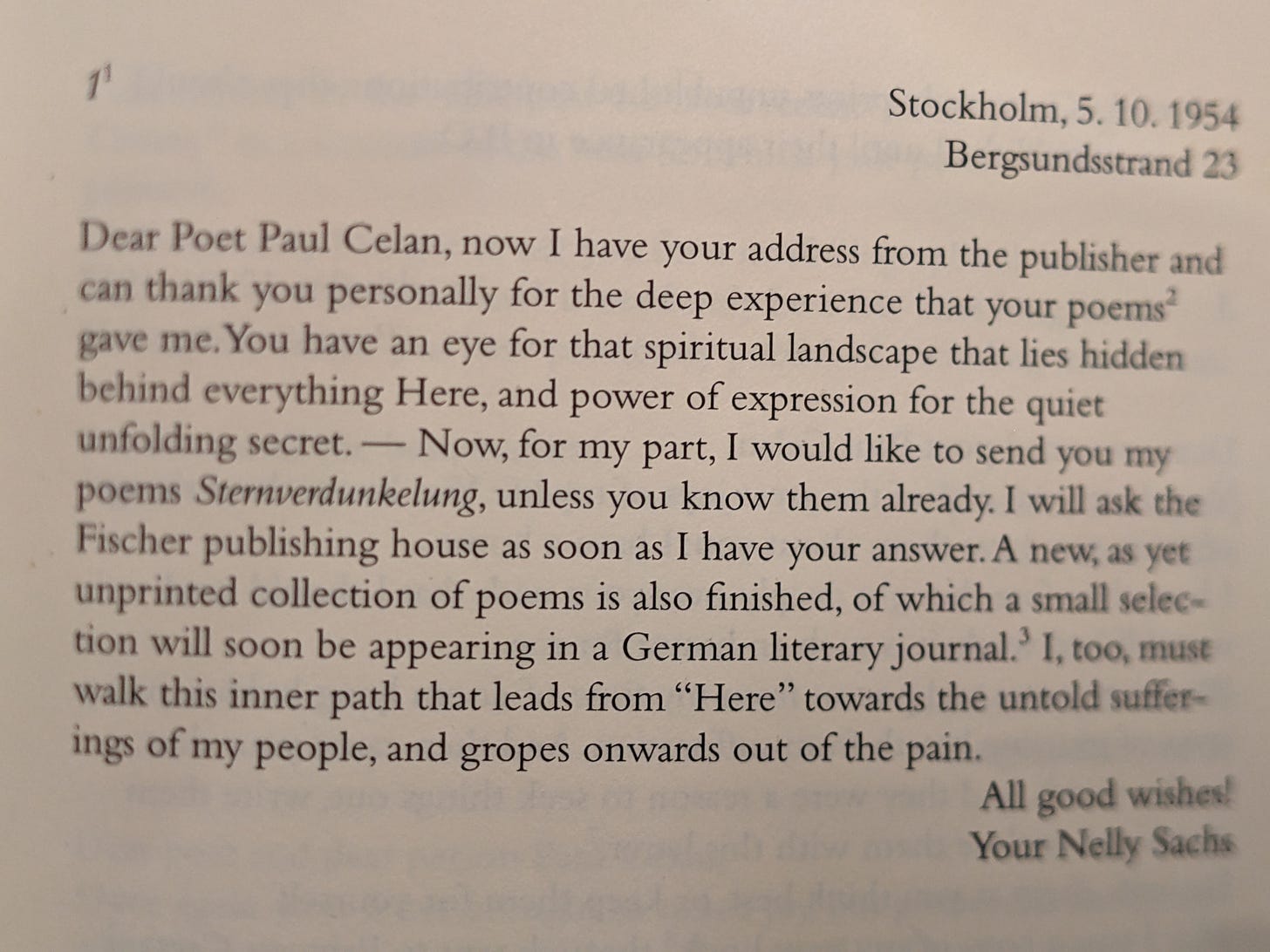

The First Letter: That Spiritual Landscape That Lies Hidden

At the start of their correspondence, Sachs does something I have always wanted to do; she thanks Celan for his poems and tells him how much they matter to her. She also dares to send him some of her own poems, which I cannot imagine doing.

At the time these letters were written, Sachs was the better-known poet. She always seems to be winning a prize in these letters, culminating in the Nobel. She’s older than Celan by 29 years and is from a different generation. Meanwhile, Celan is barely getting by. In one letter, explaining why Sachs might want to stay elsewhere when she visits, he writes that his little family “lives on top of five, unfortunately very steep, flights of stairs.”

But from the first letter onward, it is so clear that Nelly Sachs recognizes Celan as the great poet he is. She knows. “You have an eye for the spiritual landscape that lies behind everything,” she writes in her first letter, reproduced below.

For further reading on Nelly Sachs:

Six Nelly Sachs poems in translation in The New Yorker, October 1970 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1970/10/31/six-poems-4

New Translations in Notre Dame Review by Teresa Iverson https://ndreview.nd.edu/assets/188008/five_translations.pdf

The Lives of Two Survivors

Each poet had a before-life and an after-life. Nelly Sachs was born in 1891 and grew up comfortably upper-middle-class in Berlin. Early on, she wrote poems about animals, landscapes, and Mozart. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, she started writing poems with Biblical themes and she played with Chassidic mysticism in her poetry, too. In 1938, she was threatened by the Gestapo, and “the man she still loved was killed before her eyes,” the scholar and translator John Felstiner writes in his helpful introduction to these letters.

On May 16, 1940, she fled to Stockholm with her mother, helped by the novelist Lagerlöf and the Swedish royal family. Sachs and her mother moved into a one-room apartment, and Sachs began translating Swedish poetry into German.

Nelly Sachs as a young woman in 1910, at nineteen.

Celan as a young man.

Paul Celan was born Paul Antschel in Czernovitz, Romania, in 1920, in a family which spoke German. Celan, unlike Sachs, had a strong Jewish education, and he was taught Hebrew and Jewish texts. Felstiner, who wrote an amazing biography of Celan titled Poet, Survivor, Jew, described coming across the words of Isaiah—kumi ori—"arise, shine” from Isaiah 60:1 in Celan’s personal papers—in Celan’s own handwriting, in Hebrew, seen here in the draft of a poem. Look closely at the bottom two lines, where he swaps German for Isaiah’s Hebrew.

But Celan’s power as a poet comes from what he saw and lived through, not just what he read.

“Celan underwent a drastic education: Iron Guard antisemitism, Soviet occupation, Nazi invasion, ghetto, forced labor and loss of both parents,” Felstiner writes in his introduction. Celan’s poem “Deathfugue,” with its iconic opening line—“Black milk of daybreak we drink you and we drink you”—is one of the most famous poems of the Holocaust. (More links at the end of this post, including audio of Celan reading.)

For further reading:

“Deathfugue” by Paul Celan, translated from German into English by John Felstiner http://mason.gmu.edu/~lsmithg/deathfugue.html

“Deathfugue” by Paul Celan, translated by Pierre Joris https://poets.org/poem/death-fugue

Getting Closer, Letter By Letter

One joy of rereading these is watching the salutations change. In the first letter, Sachs addresses Celan as “Dear Poet Paul Celan.” By 1958 it’s “dear friend Paul Celan.” By 1959 a letter opens this way:

“Dear wondrously deep, poet Paul Celan,

I inhale your work when I go to rest in the evening. It lies beside me on the table and when the night is too hard to bear, the lamp is lit and I read again….”

Sachs and Celan get closer, and the reader feels closer to both as the letters continue.

By November 1959 Sachs addresses Celan as “Dear Brother.” He also took to calling her sister.

Kindness shines through these letters. In one letter, Sachs describes receiving reparations—20,000 Deutschmarks—for the seizure of her mother’s home under the Nazis. She wants to leave that money in her will for Celan’s son, Eric, and she does. In October 1967, Nelly writes—“Paul, dear Paul, your poems breathe with me day and night, and so they share my life.”

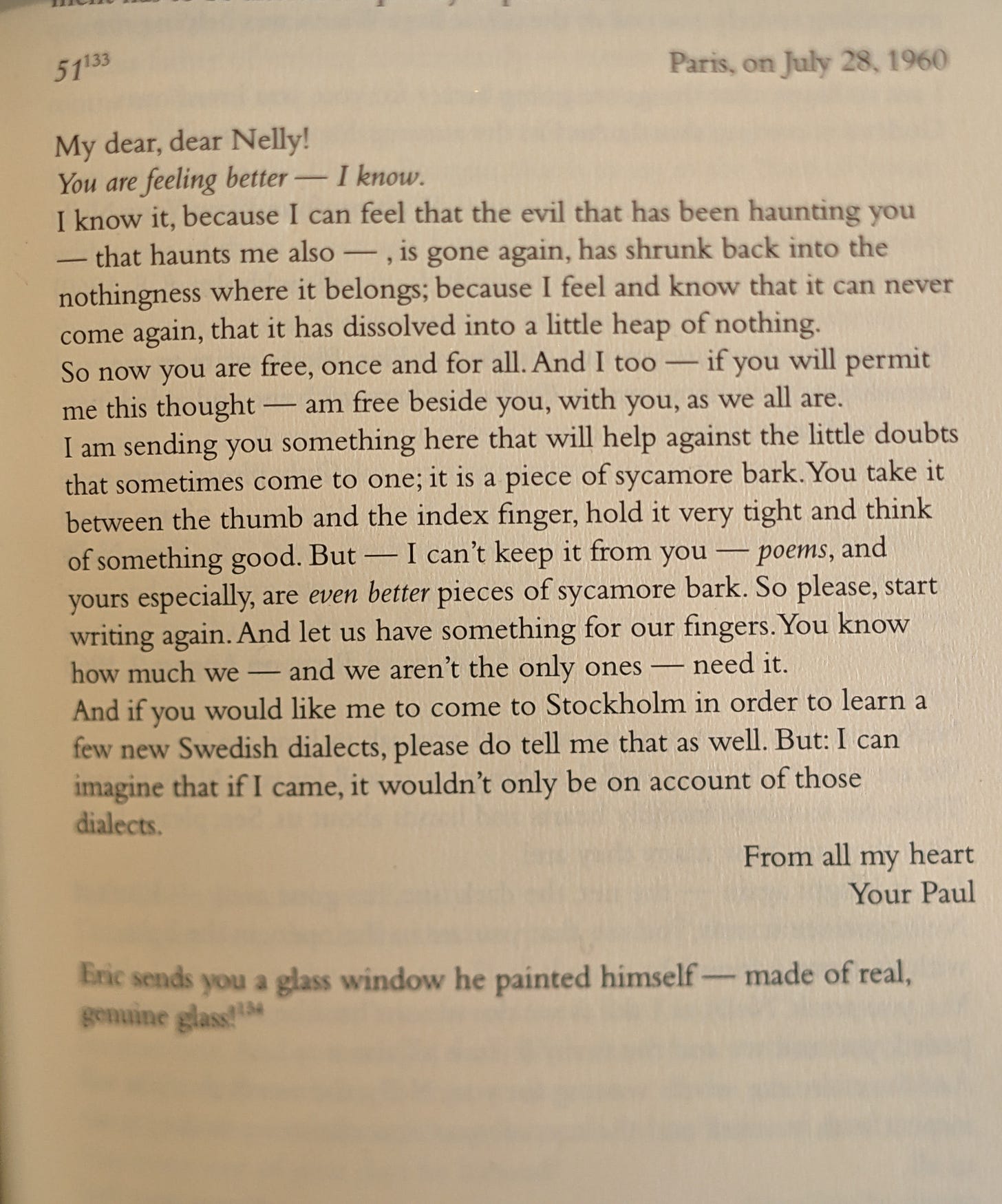

Celan as Friend--And Cure to Writers’ Block

My favorite of the letters, which I can’t stop rereading, and the second I highlight here, is when Celan sends Sachs a piece of sycamore bark. Really. Yes--he is using the piece of tree bark to encourage Nelly to believe in poetry again, and to keep writing.

The dashes that often populate Celan’s poems are here in his letter beseeching her to keep writing. So too are the italics, and the sense of music and intonation. His belief in poetry, despite everything, and his turn to the natural world for strength is here too. (Eric, mentioned at the very end, is the poet’s young son.)

A Deep Connection Through Darkness

Celan and Sachs battled with great grief and depression over what they had seen. They had seen extreme hatred, up close. In these letters, they show the private effect to someone else who understands.

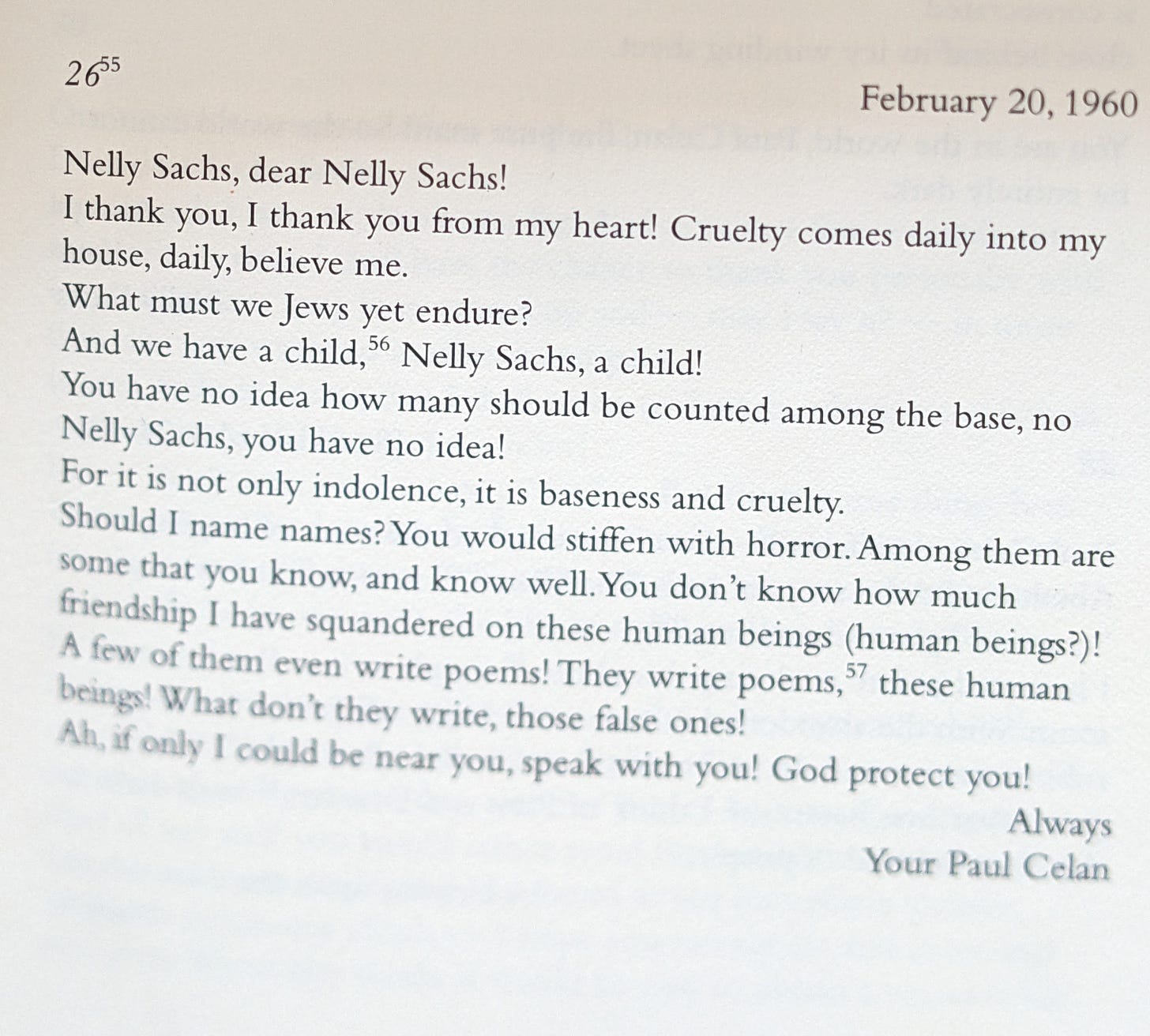

Some of the most harrowing letters here describe feeling hounded by Nazis fifteen years after the war’s end, with footnotes backing up the fact that there really were some nearby. I was shocked to read of how Celan was accused of plagiarism. In this letter, Celan expresses shock that the people who are trying to destroy him are poets.

He casts doubt on whether they are really human beings. Watch the parentheses. In Celan, punctuation, and touches like italics, really matter. “You don’t know how much friendship I have squandered on these human beings (human beings?)!

And Celan’s suffering shows no sign of ending. “Cruelty comes daily into my house, daily, believe me,” he writes Nelly.

Bits of Hebrew and Yiddish in the Letters

One of Celan’s letters has a line written in Hebrew, from the Psalms—if I forget you oh Jerusalem let my right hand…In another letter, Celan turns to Yiddish, and translates it for Sachs. Sometimes, reading about Celan in poetry publications, it is as if he had zero connection to Jewish languages when in fact he had an Orthodox upbringing and knew and wrote Hebrew. I appreciate Felstiner for pointing out the Hebrew and Yiddish here.

A passage in Felstiner’s incredible biography, Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew, describes his experience in Celan’s library. “While examining Celan’s Hebrew Bible in 1984, for instance, I found that someone from a German research team, unable to identity the volume, had placed in it a slip saying Wichtig? (Important?)

Yes—it is important.

For further reading:

I wrote an appreciation of Felstiner for the Translationista blog: https://translationista.com/2017/07/remembering-john-felstiner.html

Three books on Celan with a Felstiner connection. He introduced Celan’s letters to Sachs (left); translated the poems and prose (center); and wrote a biography (right).

Journey Into Dustlessness

Nelly Sachs referred to her “journey into dustlessness, in which all my poetry is gathered” in a 1961 letter. Celan and Sachs seem to be keeping each other alive—both as poets and as people. Celan eventually drowned himself in the Seine. On the day Celan was buried, May 12, 1970, Sachs died. Each could not live without the other.

After weeks of rereading these letters, it’s hard to imagine the world without them.

*********************************************************************************************************

For further reading and listening on Paul Celan:

Paul Celan reading “Todesfugue,” probably the most famous poem in the Holocaust. He wrote it in 1944. Note how his voice changes at the end of the poem:

Paul Celan Translating Others in World Literature Today by John Felstiner

https://www.worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/translation/paul-celan-translating-others

For further reading on Nelly Sachs:

Ed Hirsch on Nelly Sachs in The Washington Post

Daisy Fried on Nelly Sachs in The New York Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/15/books/nelly-sachs-flight-and-metamorphosis.html

********************************************************

I hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Super interesting!

Reading all that you wrote was the perfect way to start my day. I’m still moved by your description of Celan and Sachs’ correspondence and by the letters and poems you shared. Thank you!