A Poem, Broken & Whole

Reading the great poet Zelda in mourning and celebration--and watching the trailer.

In this year like no other, there are so many names.

There are the names of the dead, the names of the hostages. Each year on Yom Hazikaron, the day of remembrance in Israel, for soldiers and those lost to terror, there are names upon names, and memorial services upon memorial services. How can anyone not notice how many more names we have this year?

Then there is today, Yom Ha’atzmaut. It’s usually a celebration, the very next day after all the remembering. I’m writing this in the very last minutes, at least in my time zone, because I don’t know what to say about something.

For me the day began with chants of Yallah, yallah, ya Hamas—or “Let’s go, let’s go Hamas”—steps from where my youngest relatives take piano lessons in Chicago. The men yelling near DePaul University, cheering Hamas on, were masked; I do not know their names.

All day I have been thinking about the closeness of mourning and celebration, how remembering precedes celebrating in the calendar, and how some celebrate what others mourn, and vice versa. All day I wanted to read a poet who would quietly drown out those chants.

I turned to Zelda, the great Chassidic poet. The one and only Zelda. To my ear, she is also a great poet of quiet.

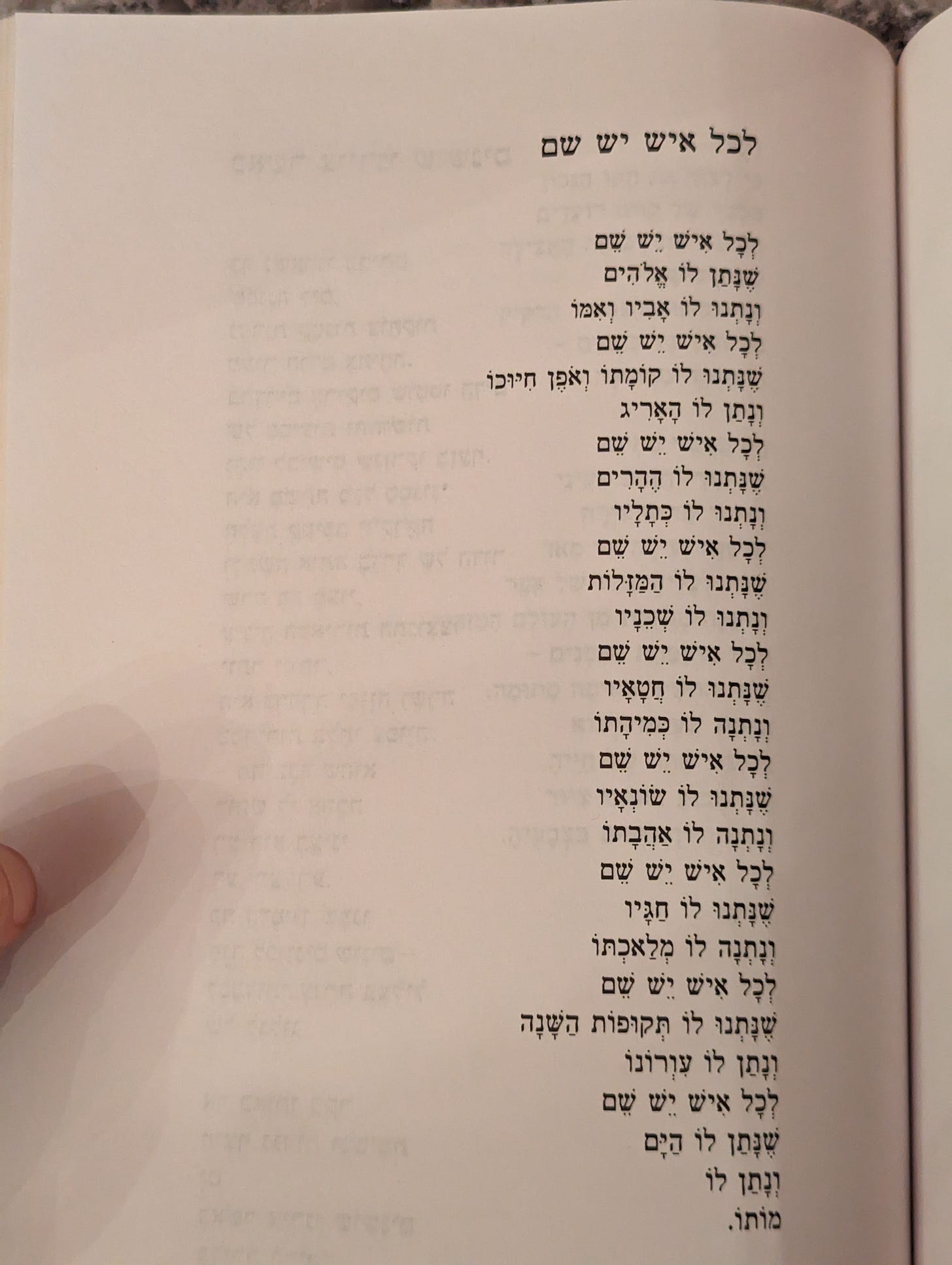

My copy of The Poems of Zelda, in Hebrew. Each of her six books was a national bestseller in Israel.

I think it’s worth learning Hebrew just to read Zelda. She was born in 1914 in Ukraine; had she lived, she would be 100 right now. And she was part of a famous Chassidic family.

“Her father was a brother of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, father of the Lubavtcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, making Zelda first cousins with the Rebbe,” Chabad’s website proudly relates. Zelda: Remembering an Israeli Poet - Chabad Lubavitch World Headquarters

She lived through the establishment of the State of Israel, and at one point, she was Amos Oz’s second-grade teacher. She was single then; he had a crush on her.

In the photo, Zelda is wearing the tichele, or head scarf, of a married woman. But when Oz encountered her, when he was in the second grade, that was not what was on her head. Decades later, he still remembered her eyes, and wrote about them.

Zelda published her first collection of poetry at age 53. Each of her six books became bestsellers in Israel. Zelda’s poetry is subtle in the most beautiful way.

There is a hidden quality to it, always. I think this must be a challenge for any translator.

Zelda in Hebrew and English

Today, trying to find a Zelda poem available in English, I discovered something very unexpected about Zelda’s famous poem “Each of Us Has a Name,” which is often read at Holocaust memorial events in Israel.

The Hebrew is a whole, but the translations aren’t, necessarily.

Look below—you will see that the original Hebrew is all one stanza. You can also see that one letter, shin, appears over and over in the poem. (It’s hard to recreate that kind of sound in English. This is one reason I love Everett Fox and his introduction to his translation of the Torah; it’s all about recreating sound.)

Even if you don’t read Hebrew, you can see the making of this poem: dainty and powerful. It’s a single column, until the last line, which is only one word — moto, or “his death”.

Here is T. Carmi’s translation, from 1996, which preserves the lone stanza:

EACH OF US HAS A NAME

Each of us has a name,

given to us by God,

and given to us by our father

and mother.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by our stature

and our way of smiling,

and given to us by our clothes.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by the mountains,

and given to us by our walls.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by the planets,

and given to us by our neighbors.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by our sins,

and given to us by our longing.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by our enemies,

and given to us by our love.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by our fast days,

and given to us by our craft.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by the seasons of the year,

and given to us by our blindness.

Each of us has a name,

given to us by the sea,

and given to us by our death.

Yet another English translation, by Marcia Falk, is in parts.

I feel that it is in some ways broken. But I still think that—in both the original and in translation—this iconic poem by Zelda is deeply relevant for this moment. I do not know why Falk chose to add stanza breaks, but I do think both versions—the Hebrew and English, whole and broken, are both beautiful, and needed.

Just like these two consecutive days, in this year of all years.

EACH OF US HAS A NAME

Each of us has a name

given by God

and given by our parents

Each of us has a name

given by our stature and our smile

and given by what we wear

Each of us has a name

given by the mountains

and given by our walls

Each of us has a name

given by the stars

and given by our neighbors

Each of us has a name

given by our sins

and given by our longing

Each of us has a name

given by our enemies

and given by our love

Each of us has a name

given by our celebrations

and given by our work

Each of us has a name

given by the seasons

and given by our blindness

Each of us has a name

given by the sea

and given by

our death.

© Translation: 2004, Marcia Lee Falk

From: The Spectacular Difference

Publisher: Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati, 2004

Zelda died in 1984, but she is very much alive in the minds of many Israeli writers.

A Film Recommendation

A few years ago, I saw the incredible and intimate Zelda documentary when it premiered in Jerusalem, and I cried. You can watch the trailer for Zelda: A Simple Woman for free online—there are subtitles. (Link below.) You can see glimpses of Zelda’s famously modest tiny apartment and watch Amos Oz reading a passage he wrote about Zelda’s eyes.

I feel her quote at the beginning fits the complicated feelings many of us have this week. And yet Zelda, the great poet of widowhood, always offers hope. I can listen to her discuss the “sense of the secrecy of life, the sense of the light that comes from beyond the material world” for days.

Watch Zelda – A Simple Woman Online | Vimeo On Demand on Vimeo

*********************************************************************************************************

Hope this newsletter brought meaning. Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

What a gorgeous thing this is, even in English, as a long column insisting given to us given to us. It reads like a prayer, which we need. I love the quiet too. Thank you Aviya.

Thank you for bringing Zelda to my attention. I had not read or heard of her before! And I grew up Chassidic. Reading both the Hebrew and English side by side makes a huge difference because in Hebrew the language (words too!) contains references to texts not familiar to English readers. I'm thinking for example of the poem "al tashlichenu" (trans: "Cast Me Not Away") which takes off from phrases of high holiday liturgy.