I reread the poem “Hashkivenu With Ritual Immersion” after speaking to my friend in Tel Aviv, who asked me to watch the Israeli news online and call her when I heard a missile alert—because she is so tired from running back and forth to the shelter that she nearly slept through a siren.

This poem by Leah Falk was originally published in print form in Gulf Coast, the literary magazine published at The University of Houston, but part of it is the ancient Hebrew prayer hashkivenu, which begins “lay us down to sleep in peace, God.”

To understand the poem, you need to recognize the prayer. Here is the Hebrew prayer, followed by an English translation:

הַשְׁכִּיבֵֽנוּ, יְיָ אֱלֹהֵֽנוּ, לְשָׁלוֹם, וְהַעֲמִידֵנוּ שׁוֹמְרֵֽנוּ לְחַיִּים, וּפְרֹשׂ עָלֵֽנוּ סֻכַּת שְׁלוֹמֶֽךָ, וְתַקְּנֵֽנוּ בְּעֵצָה טוֹבָה מִלְּפָנֶֽךָ, וְהוֹשִׁיעֵֽנוּ לְמַֽעַן שְׁמֶךָ. וְהָגֵן בַּעֲדֵֽנוּ, וְהָסֵר מֵעָלֵֽינוּ אוֹיֵב, דֶּֽבֶר, וְחֶֽרֶב, וְרָעָב, וְיָגוֹן, וְהָרְחֵק מִמֶּֽנּוּ עָוֹן וָפֶֽשַׁע. וּבְצֵל כְּנָפֶֽיךָ תַּסְתִּירֵֽנוּ, כִּי אֵל שׁוֹמְרֵֽנוּ וּמַצִּילֵֽנוּ אָֽתָּה, כִּי אֵל חַנּוּן וְרַחוּם אָֽתָּה. וּשְׁמֹר צֵאתֵֽנוּ וּבוֹאֵֽנוּ לְחַיִּים וּלְשָׁלֹם מֵעַתָּה וְעַד עוֹלָם.

.בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, שׁוֹמֵר עַמּוֹ יִשְׂרָאֵל לָעַד.

And here is an English translation of the prayer from Havurah Shalom, Portland’s Reconstructionist community website. It’s close to a version at Sefaria too. I’m used to the Hebrew, where the word hashkivenu shares a sound and a letter—shin—with the word shalom. (If you don’t read Hebrew, the “shin” is the second letter on the first line, reading from right to left. You can see how that letter repeates often in the first line, and throughout the prayer.)

The next phrase in the Hebrew has fros, or spread, with a sin letter and sound, followed by sukkat which has the same s sound but is written with a samech. (The letter sin looks exactly like shin, except the dot above is in a different place.) The translations don’t catch that sound-play, or that visual similarity, but this one does catch the general meaning of asking God to sleep in peace and to be protected:

Lay us down to sleep in peace, Adonai our God, and raise us up, our leader, to life; spread over us the shelter of your peace. Guide us with your good counsel, and save us for the sake of your name. Shield us from foe, plague, sword, famine and anguish. Remove wrongdoing from before us and behind us, and shelter us in the shadow of your wings. For it is you, O God, who protects and rescues us; it is you, O God, Who are our gracious and compassionate leader. Safeguard our coming and our going, to life and to peace from now to eternity. Blessed are you, Adonai, who spreads a shelter of peace over all of us.

Many people know this prayer by heart, because it is said daily.

“The Hashkiveinu prayer is part of a set of rabbinic readings that bracket the biblical text of the Shema during evening prayers on both Shabbat and weekdays,” Rabbi Hara Person, the publisher of CCAR Press, writes. “The prayer envisions God as a guide and shelter during the night ahead and praises God for watching over us, delivering us, and being merciful.”

Rabbi Hara Person.

I was moved by Rabbi Person’s observation about why the prayer is soothing. “There’s something profoundly comforting about the basic human terms in which this prayer speaks. Some prayers focus on lofty themes that can feel removed from our daily lives, but Hashkiveinu gives voice to our deepest fears. We ask for God to watch over us and guard us as we sleep, enabling us to rest peacefully and wake up again in the morning restored to life. It doesn’t get much more primal than that.” (You can read more here.)

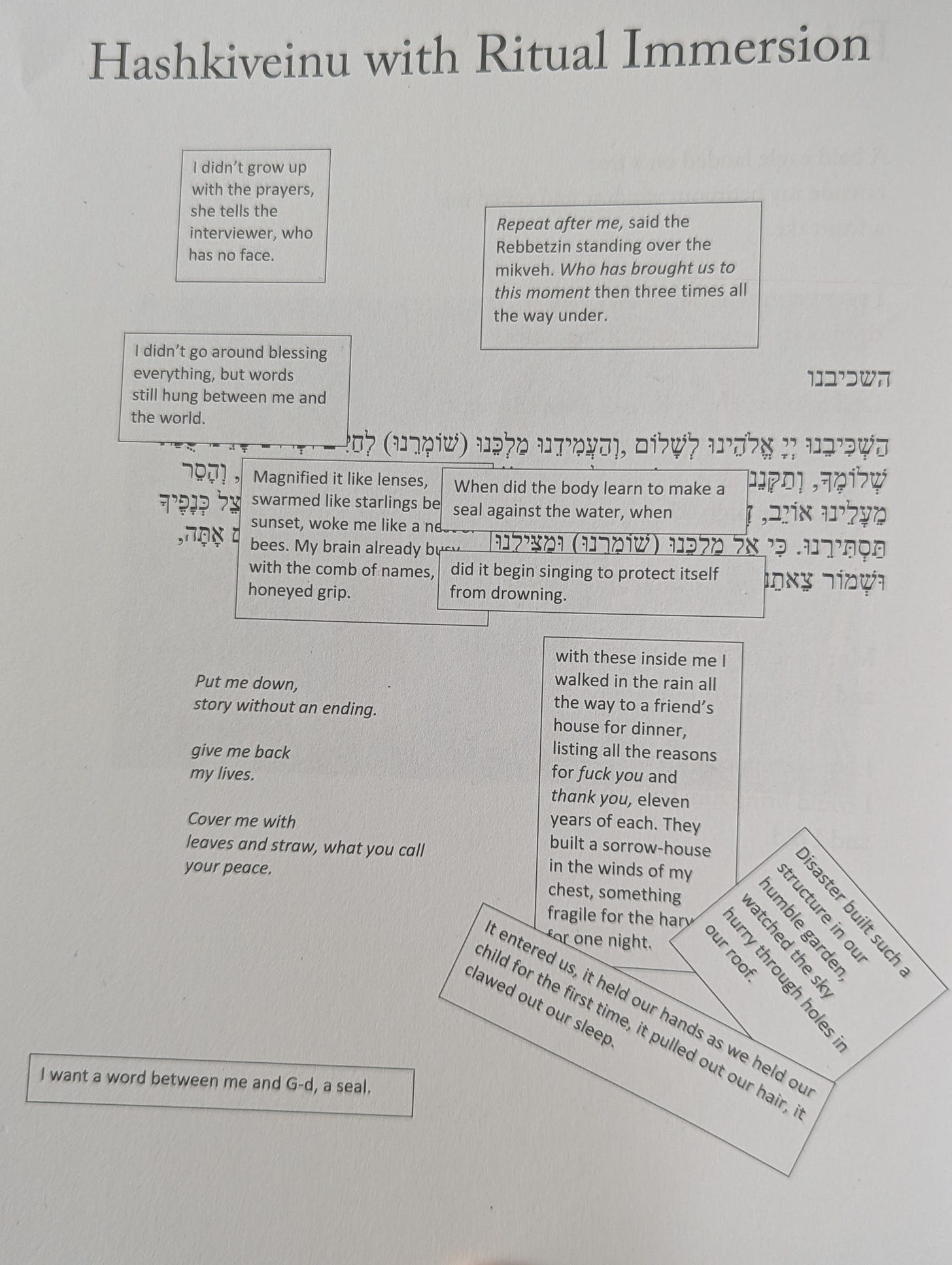

The poem title starts with a transliterated Hebrew word—"hashkiveinu,” or lay us down, or perhaps let us rest. It’s the beginning of one of my favorite prayers. And yet poet Leah Falk writes, in the box to the left, that she didn’t grow up with the prayers.

Poet Leah Falk. (Photo credit: Sam Reed)

“I didn’t grow up with the prayers, she tells the interviewer, who has no face,” is how the poem begins, reading from left to right. But of course, you could also read it Hebrew-style, and start on the right. Then you would begin with: “Repeat after me, said the Rebbetzin standing over the mikvah. Who has brought us to this moment then three times all the way under.”

This poem, like the hashkivenu prayer, engages both the eye and the ear. I find myself returning to the various boxed sections, just as I return to phrases in the hashikevenu prayer.

Take a look at the bottom left, for instance—”I want a word between me and G-d, a seal.”

And immerse yourself in the lines about immersion, and about disaster…which you can see on the right. I’m grateful to Gulf Coast for publishing this poem, with all its complexity.

Leah Falk is the author of Other Customs and Practices (Glass Lyre Press, 2023) and To Look After and Use (Finishing Line Press, 2019). She is the Director of Education and Engagement at Penn Live Arts and lives in Philadelphia. As always, I encourage readers to request books from the library, and buy books if you can—and I’m interested in your thoughts on the poem, and its intriguing engagement of both eye and ear. Wishing all of us, wherever we are in this difficult moment, a night of peace.

***********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Beautiful! Thank you!