A Poet's Journals of Refuge & Light

The French poet and translator Mireille Gansel's private world.

It is almost impossible to find homes for essays on Jewish poetry, and especially Jewish poetry in translation. What about an essay on a Jewish poet’s journals in translation? Even more impossible.

I thought of all kinds of impossibilities as I read Soul House by Mireille Gansel, translated from the French by Joan Seliger Sidney, and recently published by World Poetry. Soul House is the poet’s journal, but more accurately, it is an attempt to find a home for a soul.

One impossibility is that this is a book that is nearly impossible to categorize. Pierre Joris, who translated Paul Celan for decades, calls Soul House “truly nomadic writing.” Poet Ilya Kaminsky describes it as “ghost-breath in scraps of tales almost told.” The ghost-breath can be felt in section titles, like “house of words” and “words as shelter”.

Nearly all the sections in Soul House begin with a sentence that begins in lowercase. The lack of capitalization adds to the feeling that it is all one piece, one search for home.

I want to highlight four snippets from this unusual book, which begins in childhood and then explores the themes of refuge and meaning. The 159-page book is a bilingual French-English edition, so this is really a spare book of just under 80 pages. But the voices it invokes are anything but spare; the book mentions poets Nelly Sachs, Paul Celan, and Mahmoud Darwish; essayist and thinker Walter Benjamin; the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, in an extended sequence; and Elie Wiesel, and his memoir, Night.

About Mireille Gansel

Mireille Gansel is the author of seven collections of poetry in French, and she is a celebrated translator of German and Vietnamese. Gansel was born in France in 1947; her parents had arrived as refugees. Her father was a Hungarian Jew, but the family spoke German at home; her parents also spoke Yiddish. Gansel’s lyrical memoir, Translation as Transhumance, translated into English by Ros Schwartz, is considered an important book in the field of translation studies. Sidney, the translator, is the author several collections of poetry including Body of Diminishing Motion.

Poet and translator Mireille Gansel.

This book is graced by a foreword by the poet Fanny Howe and an intriguing afterword by Michèle Ganem Gumpel, a scholar of contemporary expressions of memory and questions of time. In her preface, Howe describes all the languages and all the displacement that shaped Gansel’s childhood. “Other nearby cities filled up with displaced people from all around Europe where their homes had been shelled to dust. Multiple languages filled the schools and stores.”

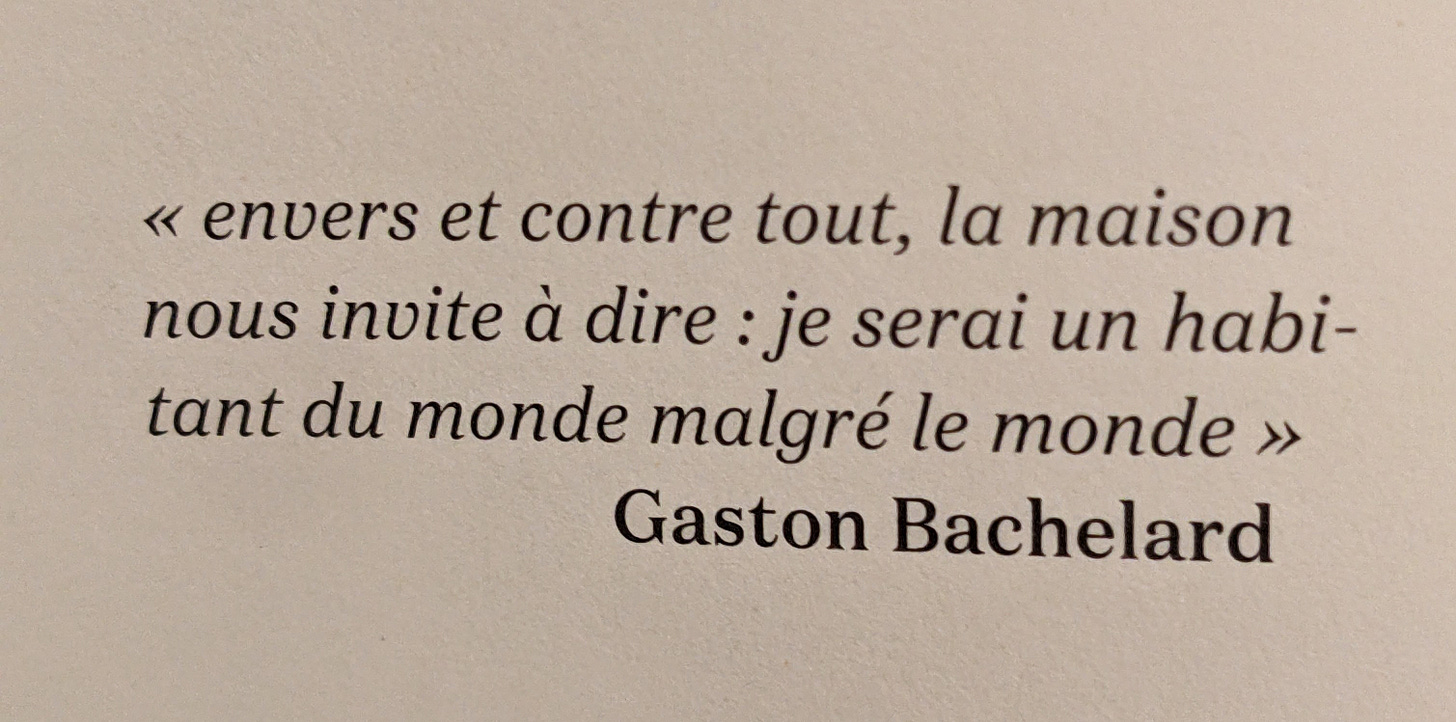

That preface gives a sense of how Gansel became who she became. So, too, does the epigraph, from the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, which I am including here because I loved it and because it fits this book perfectly.

Where to Live Leaving No Trace?

Yes—”I will be a citizen of the world despite the world.”

It’s a line that feels especially apt right now. The first section I want to highlight is about Gansel’s childhood home, which is clearly one of the main forces that shapes the book and her work as a whole. It is the place where the desire to be a citizen of the world despite the world must have been initially sparked.

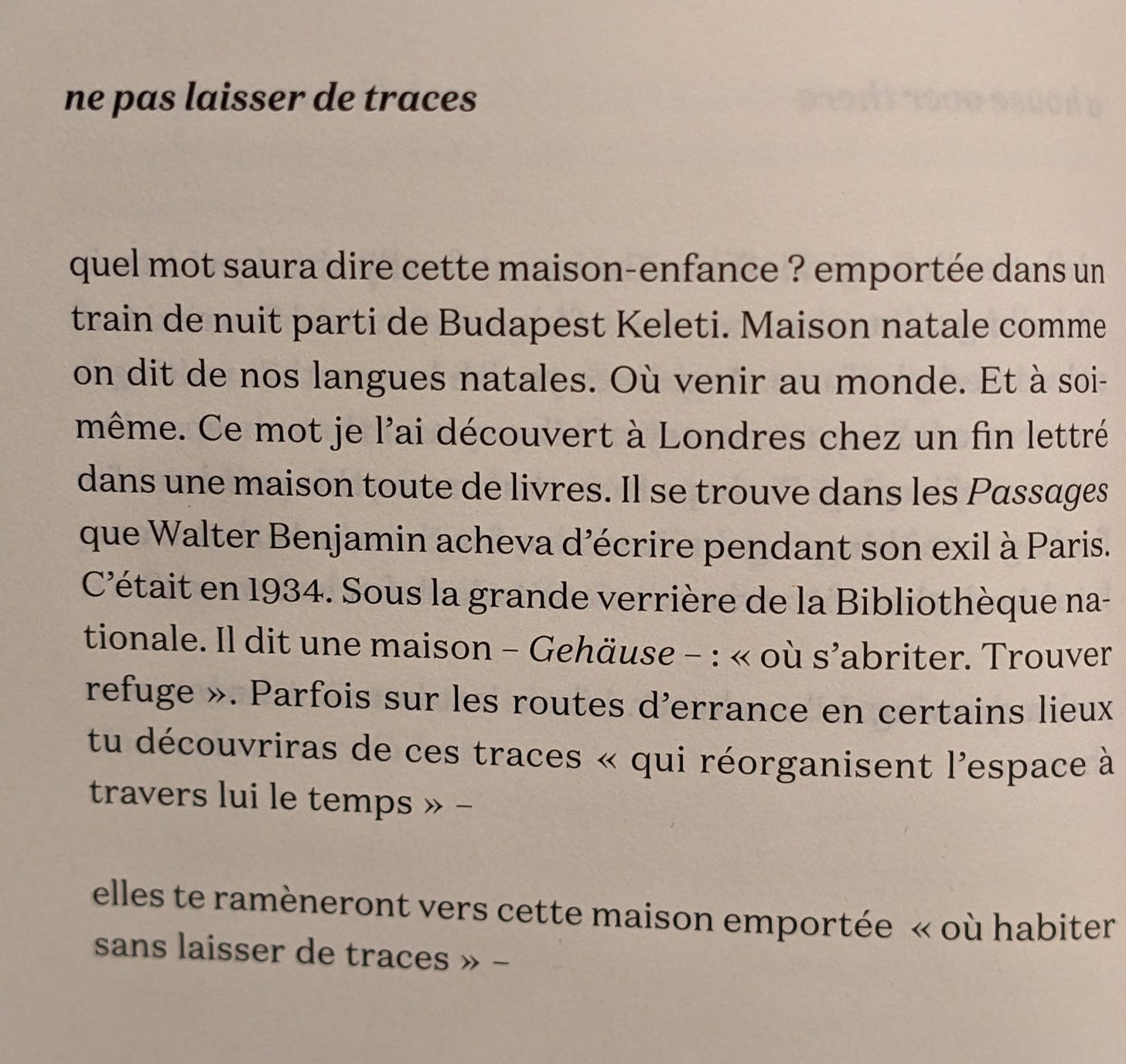

Gansel quotes Walter Benjamin’s take on a house; just as Benjamin struggled to express the role of a house and time, so does Gansel. And something about seeing Benjamin’s German in the French adds to the feeling of nomad-ness that Joris mentions. Gansel’s translator, Joan Seliger Sidney, was wise to preserve Benjamin’s German in her English version, as you can see near the end of the first paragraph (or should I say stanza?):

The Light of Words

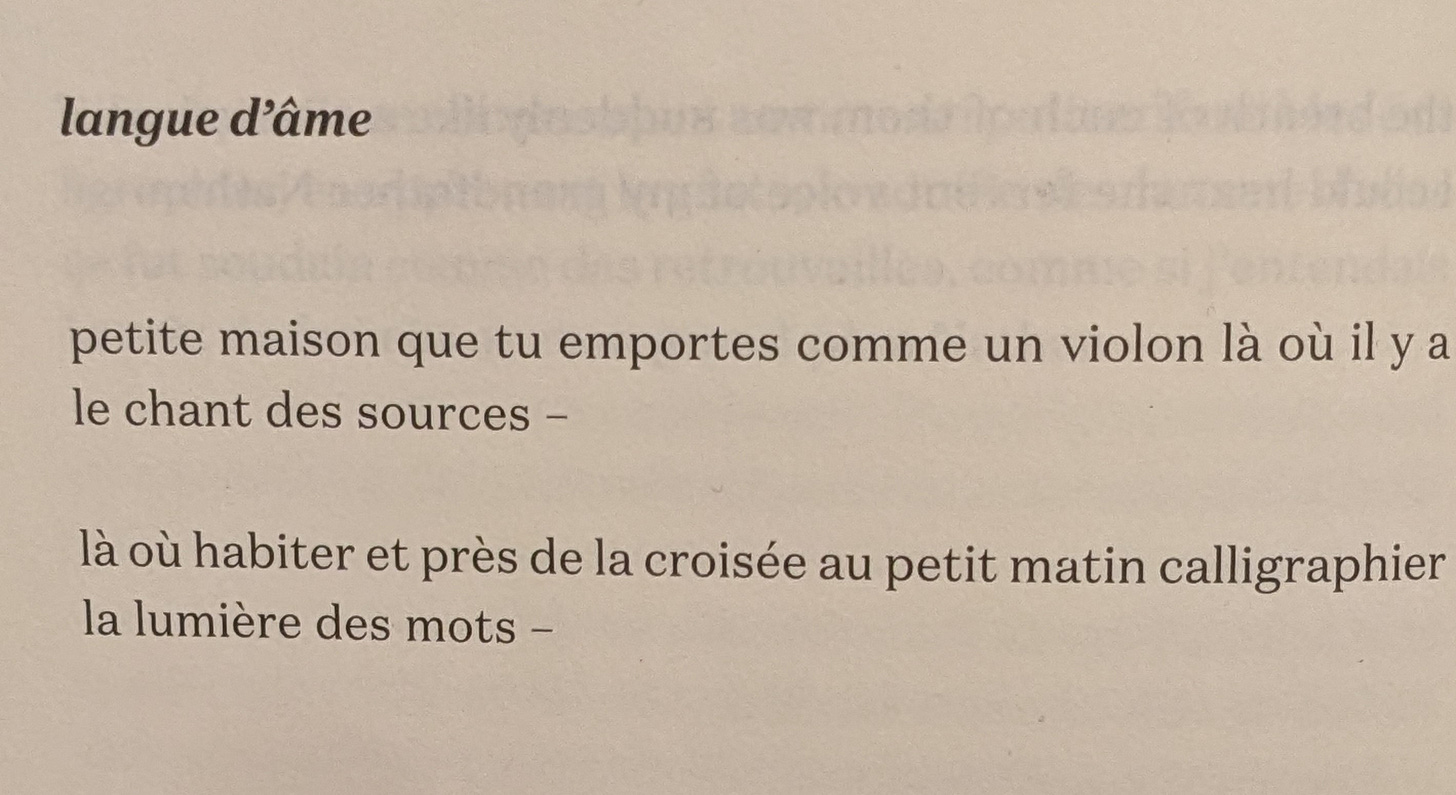

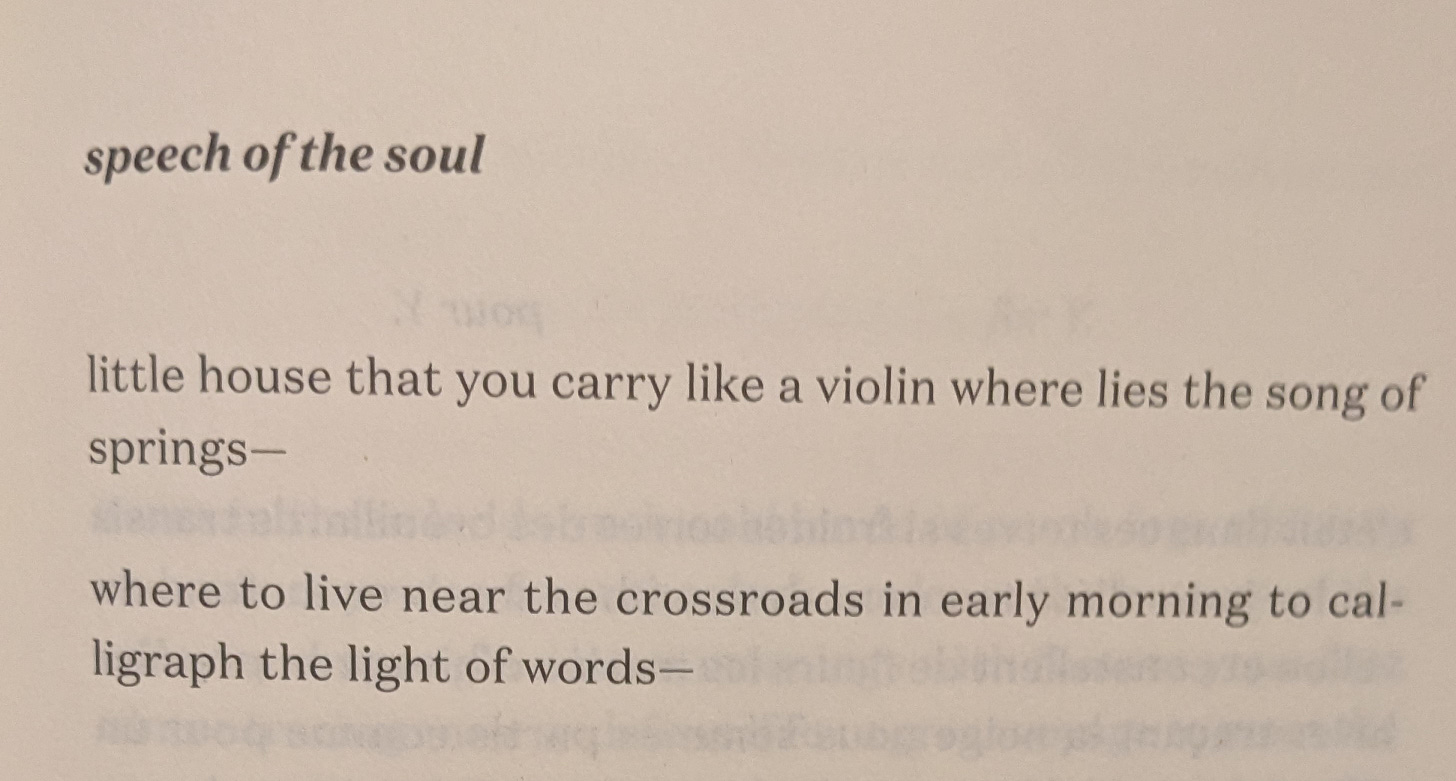

Next are two sections that both work with light. First, in “speech of the soul,” an early-morning glimpse of the need to “calligraph the light of words”:

Notice how the last few words—“la lumière des mots” or “the light of words” — become a section title later in the book. It’s an example of how the entire book is woven together, and how different sections speak to each other.

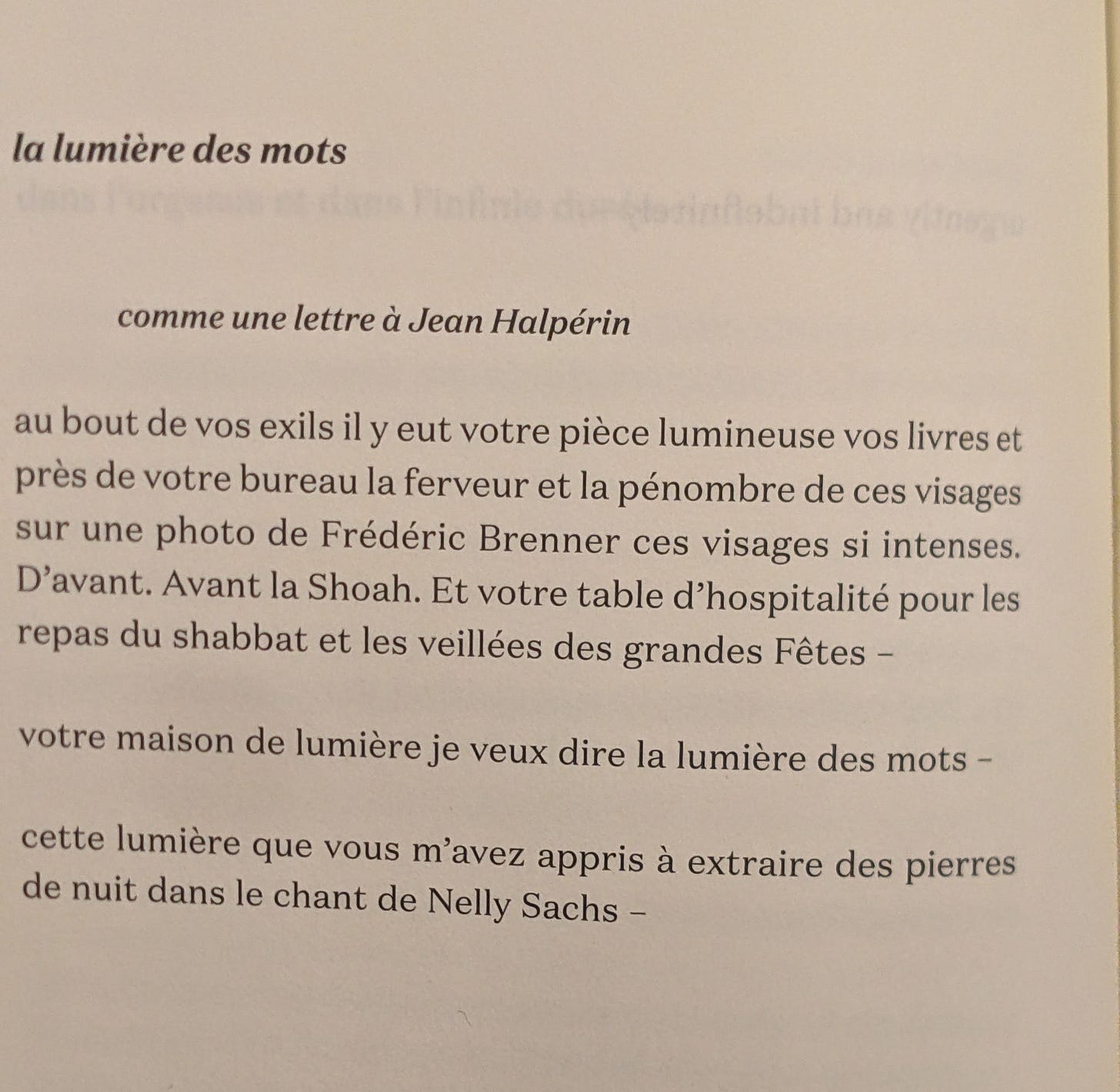

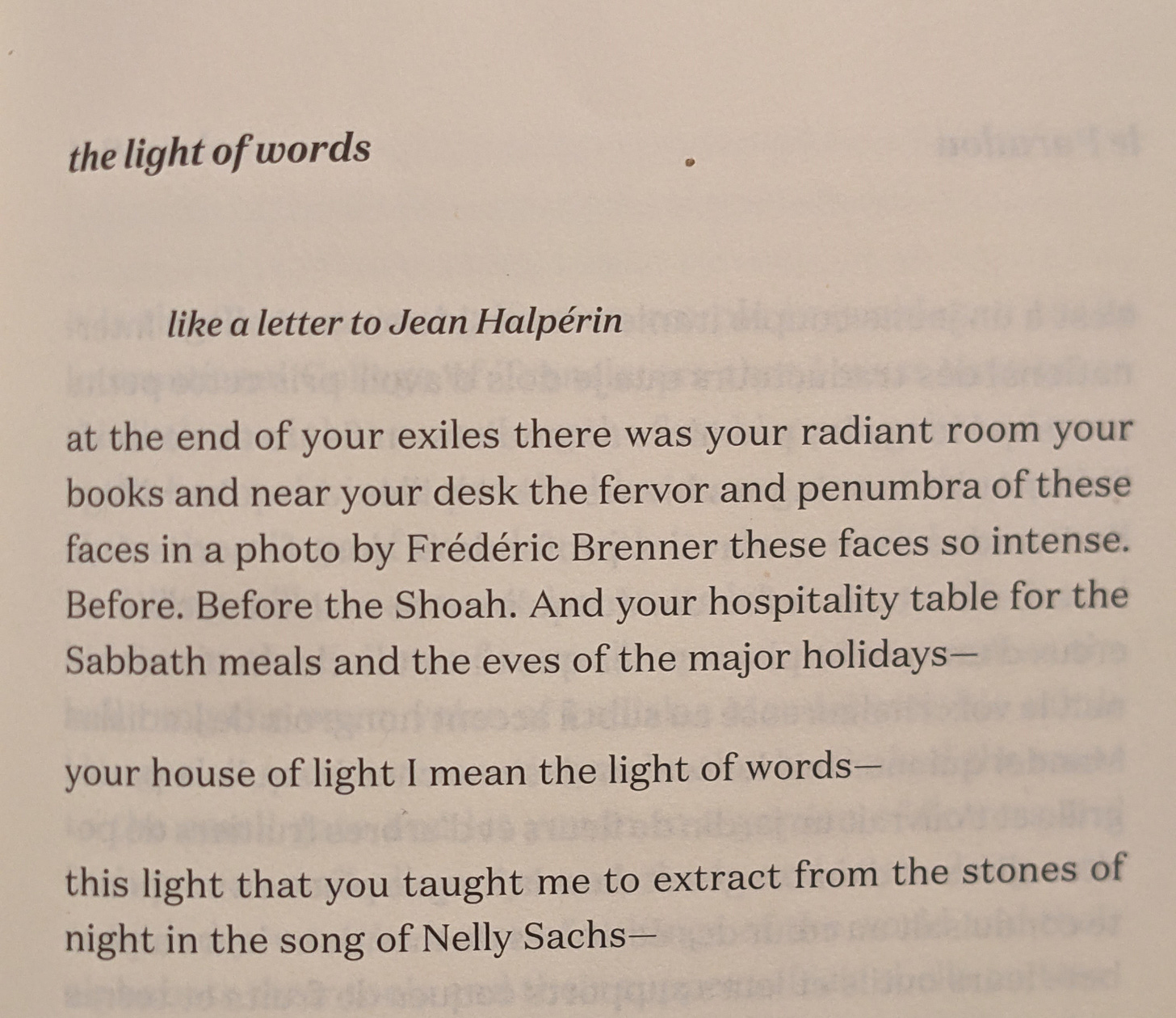

In the section “the light of words,” I especially love the line “your house of light I mean the light of words”—probably my favorite line in the entire book. In the French, the line has the added beauty of the repeating “v” in votre followed a bit later in the line by veux:

The Jewish-ness of this book is especially evident here, with the phrase “the end of your exiles,” the invocation of the before-times—in this case, before the Shoah—and the Shabbat table. (The word “Before.” felt especially haunting now.) There is also a mention of the Jewish poet Nelly Sachs, soul-friend of Celan’s, who shared the Nobel Prize with the great Hebrew fiction writer Shmuel Yosef Agnon, generally referred to as Shai Agnon.

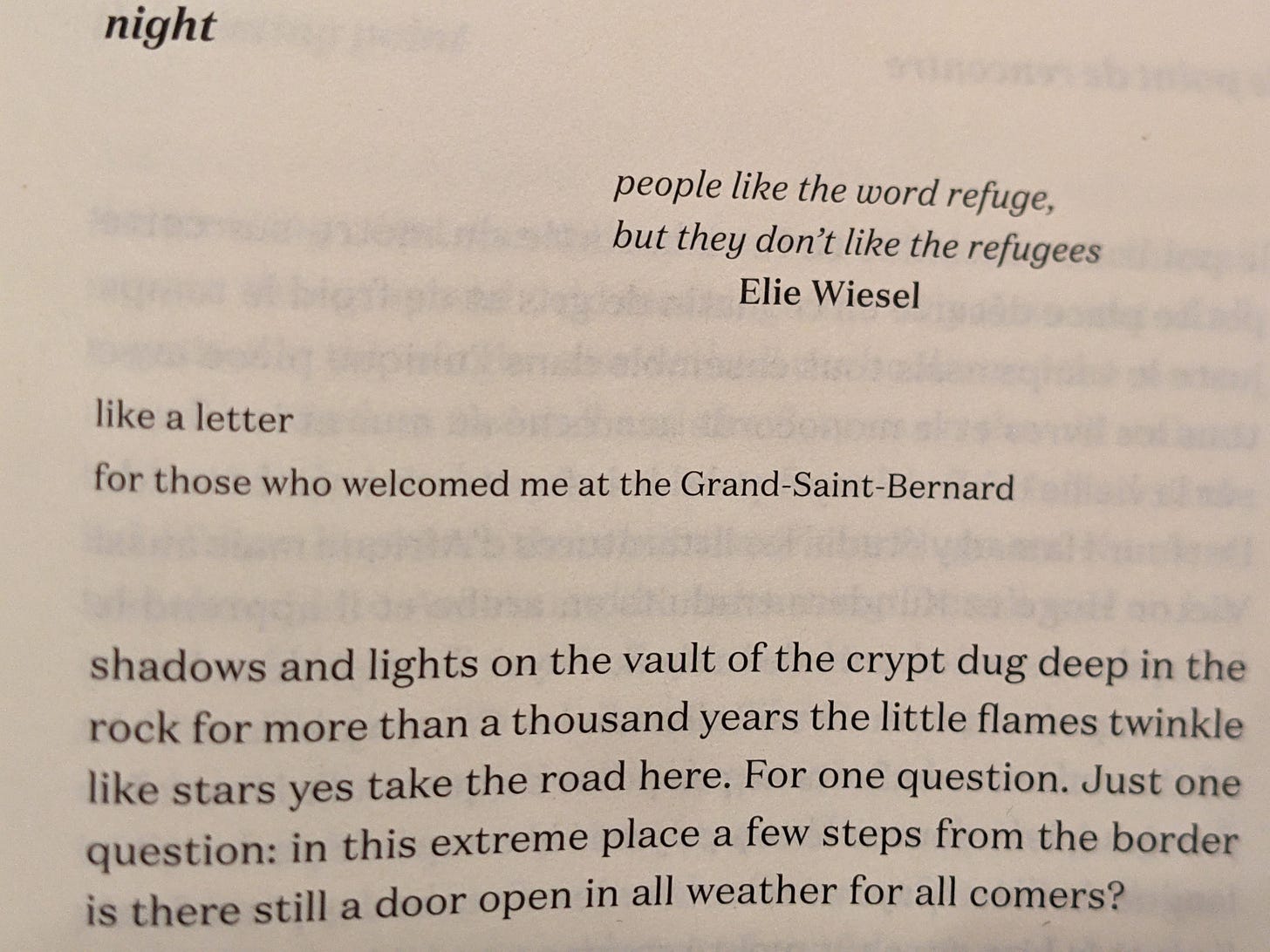

Finally, I am intrigued by this wrestling with the thought of Elie Wiesel, author of Night. Gansel’s section is also called “Night” and it has an epigraph from Wiesel at the top: “People like the word refuge, but they don’t like the refugees.”

New Essay on Chava Rosenfarb Is Up

Speaking of refugees, and “a door open in all weather for all comers,” I have a new essay up in The Forward about the great Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb and her collected stories, recently published in English translation. I spent months with Rosenfarb’s stories about the afterlives of Holocaust survivors, who remade their lives to freezing Canada after fleeing Europe.

I have been in Rosenfarb mode for months. In a previous newsletter, in the “Before.” times, I wrote about reading James Baldwin and Chava Rosenfarb and their shared interest in a surprising question—do you love me? In case you missed it:

https://aviyakushner.substack.com/p/love-and-destruction-reading-james

Photo of a street mural depicting the great Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb in Lodz, Poland. (photo: Kathryn Hellerstein)

Here is my review essay on Rosenfarb’s collected stories in The Forward:

Gratitude and What’s Ahead

As I pass the four-month mark with this newsletter, I am so grateful to all who subscribed, shared, commented, and emailed, and especially to the paid subscribers making it possible to continue and expand. I will be adding new features—and I welcome your support to make them a beautiful reality.

On January 17th at 2 CST/ 3 EST, I will be co-hosting “Writers and Hope,” the first of several winter salons for paid subscribers. My co-host will be the fantastic fiction writer Christine Sneed, who writes Bookish on Substack. We will talk about writers from the past who have had crises of hope, and our personal strategies for remaining hopeful as writers—especially as we both work on books that take a long time.

I often reread Christine’s sublime first book of stories, Portraits of a Few of the People I Have Made Cry. And in a little-known fact, Christine, also the author of the novels Little Known Facts and Paris, He Said, was a French major in college.

For resolution season in January, we look forward to replenishing our own reserves of hopefulness—because writing requires a belief in the future in order to happen. And of course, we will both be happy to answer questions. In this difficult moment, I wish you the light of words, and a soul house, wherever you may be. Shabbat shalom!

********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing wtih depth.