Are We Here to Be God’s Body or God’s Language?

Reading Richard Michelson's poetry in a time of trouble.

One of the pleasures of this busy, complicated, emotional and war-tinged summer was reading Richard Michelson’s poetry. The title of this newsletter is a borrowed line from one of his poems—poems which made me think, pause, and recognize that many of us are facing complex questions that we may be too scared to name.

In a time when many writers—and everyday citizens of all backgrounds and fears—are afraid to comment on the historic Black-Jewish alliance, and whether it is fraying, or still strong beneath it all, Michelson goes there again and again as he explores the ramifications of the rise in hatred and violence we have all observed in recent years.

I think this willingness to comment is rooted in the story of his own father, the last Jewish shopkeeper on the block, who was shot and killed by a young Black man who was addicted to drugs.

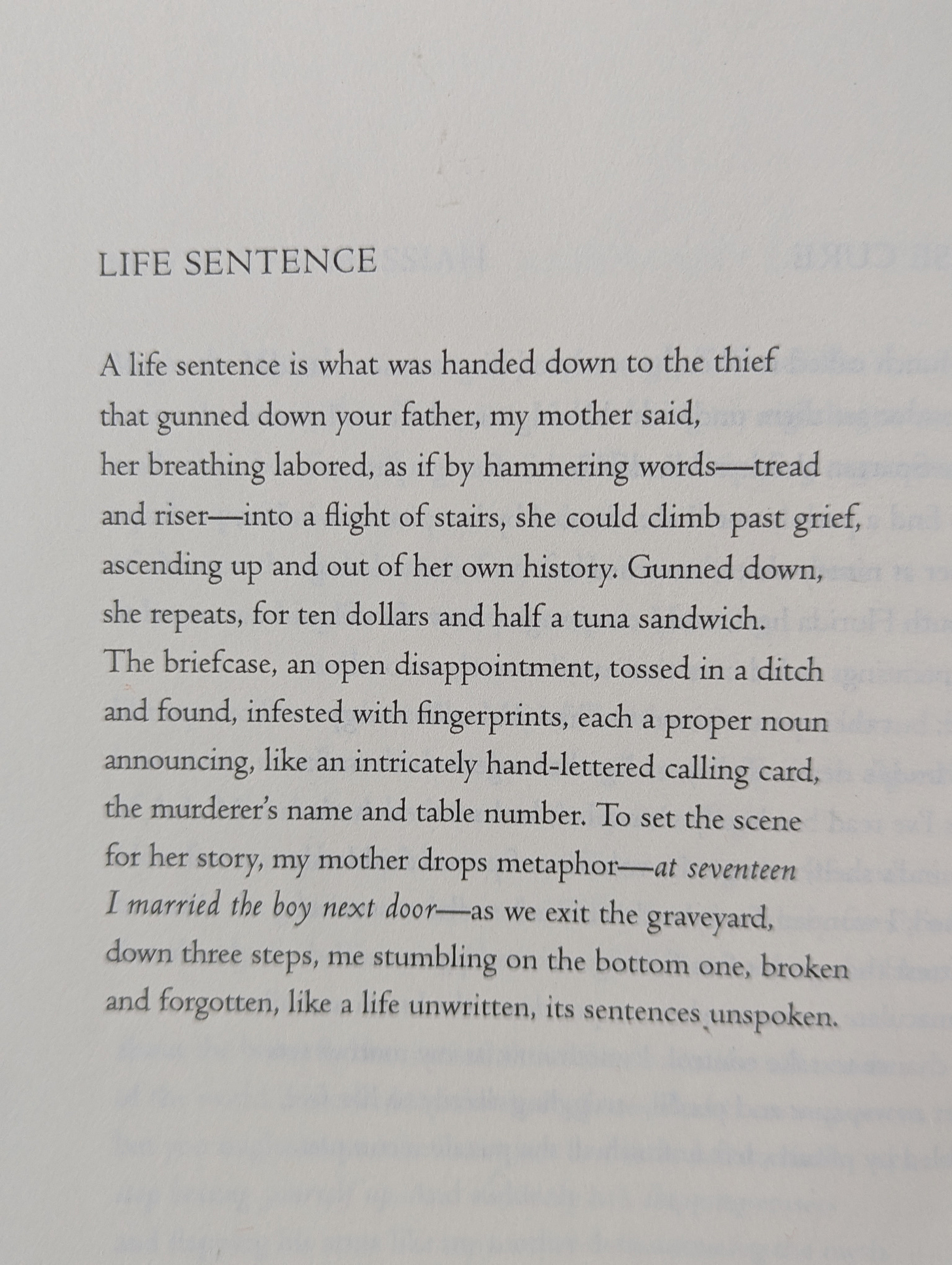

One of the most haunting moments in this collection is a double take on that murder—two poems titled “Life Sentence,” which face each other in his latest collection, Sleeping as Fast as I Can, published by Slant Books in 2023. Michelson is an award-winning poet and children’s book author who won the 2017 National Jewish Book Award for his children’s book, The Language of Angels: A Story About the Reinvention of Hebrew. He hosts Northampton Poetry Radio, and served two terms as Poet Laureate of Northampton, Massachusetts.

These two “Life Sentence” poems reminded me of a long-ago comment by the poet, literature scholar, and acclaimed painter Peter Sacks about writers and their subjects. He was my teacher when I was an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins—and is now at Harvard; as he introduced the poems of Louise Glück and Jorie Graham, Professor Sacks liked to say that “every writer has wells he or she cannot stay away from.”

To my ear, Michelson’s father is one of his great wells.

The concept of a “life sentence” is one the poet always returns to; it is his source of water. Something about the doubleness of two poems, facing each other, emphasizes that it changed everything for father and his mother; for father and son; and victim and perpetrator.

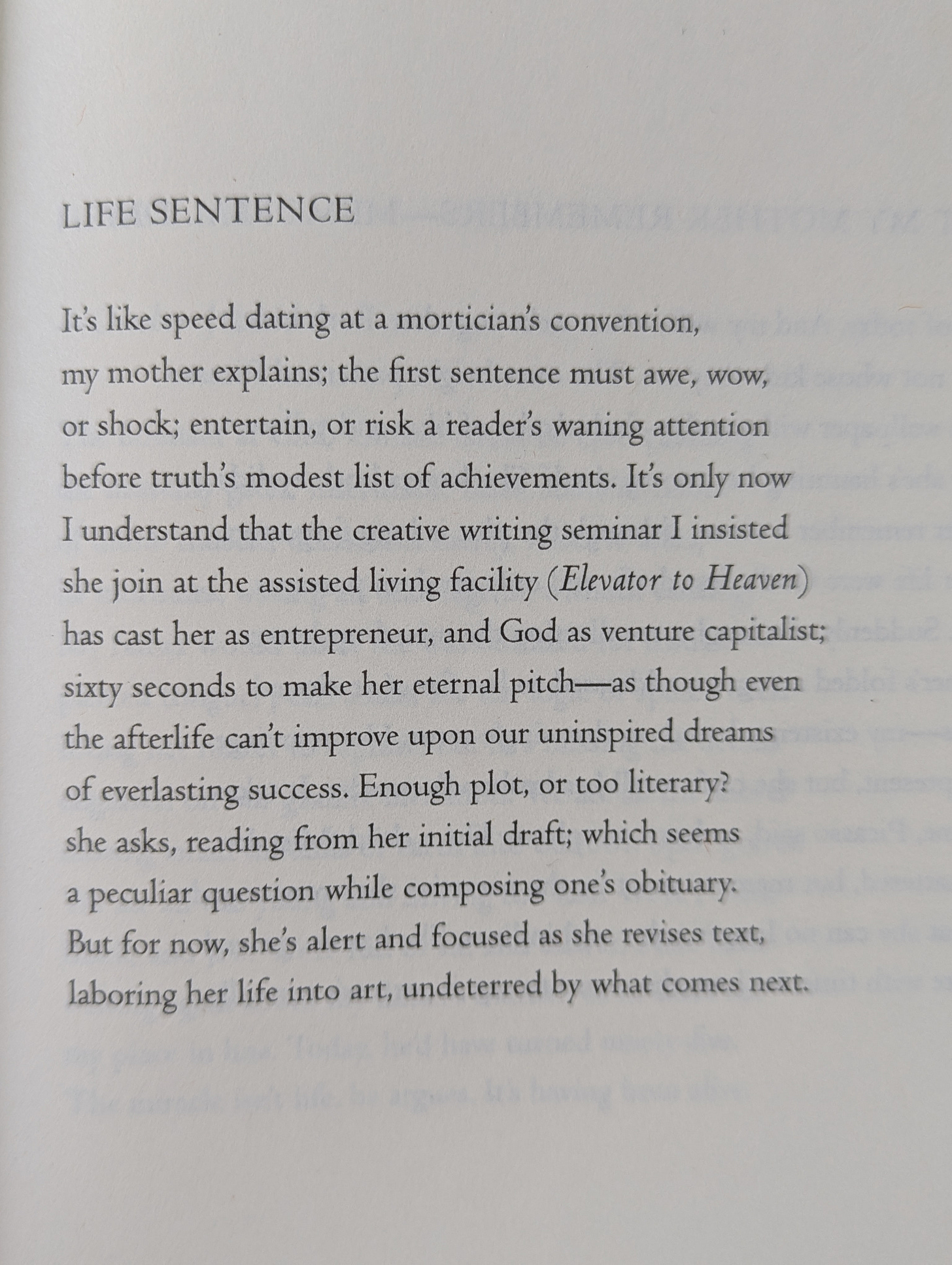

In the second “Life Sentence,” Michelson gives his mother center stage. And as he often does, he includes God. This time, it’s “God as venture capitalist.”

Both these “Life Sentence” poems are Shakespearean sonnets—14 lines long with a final couplet that rhymes. Interestingly, while its roots are in Europe, the sonnet is experiencing a revival in America. For example, Frank: Sonnets by Diane Seuss, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2022, included the memorable line—“The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without.”

Michelson has no shortage of memorable lines, and the sonnet form makes the most of them.

“It’s like speed dating at a mortician’s convention” spotlights his mother’s sense of humor, and his. Michelson grew up in East New York, a tough neighborhood in Brooklyn that was and is a far cry from the gentrified neighborhoods that people think of when they hear “Brooklyn” today. You can hear that hard-knuckled childhood in a challenging poem that I keep returning to, which from the title onward spares no one. It’s a bit long for a newsletter, but I can’t resist featuring it.

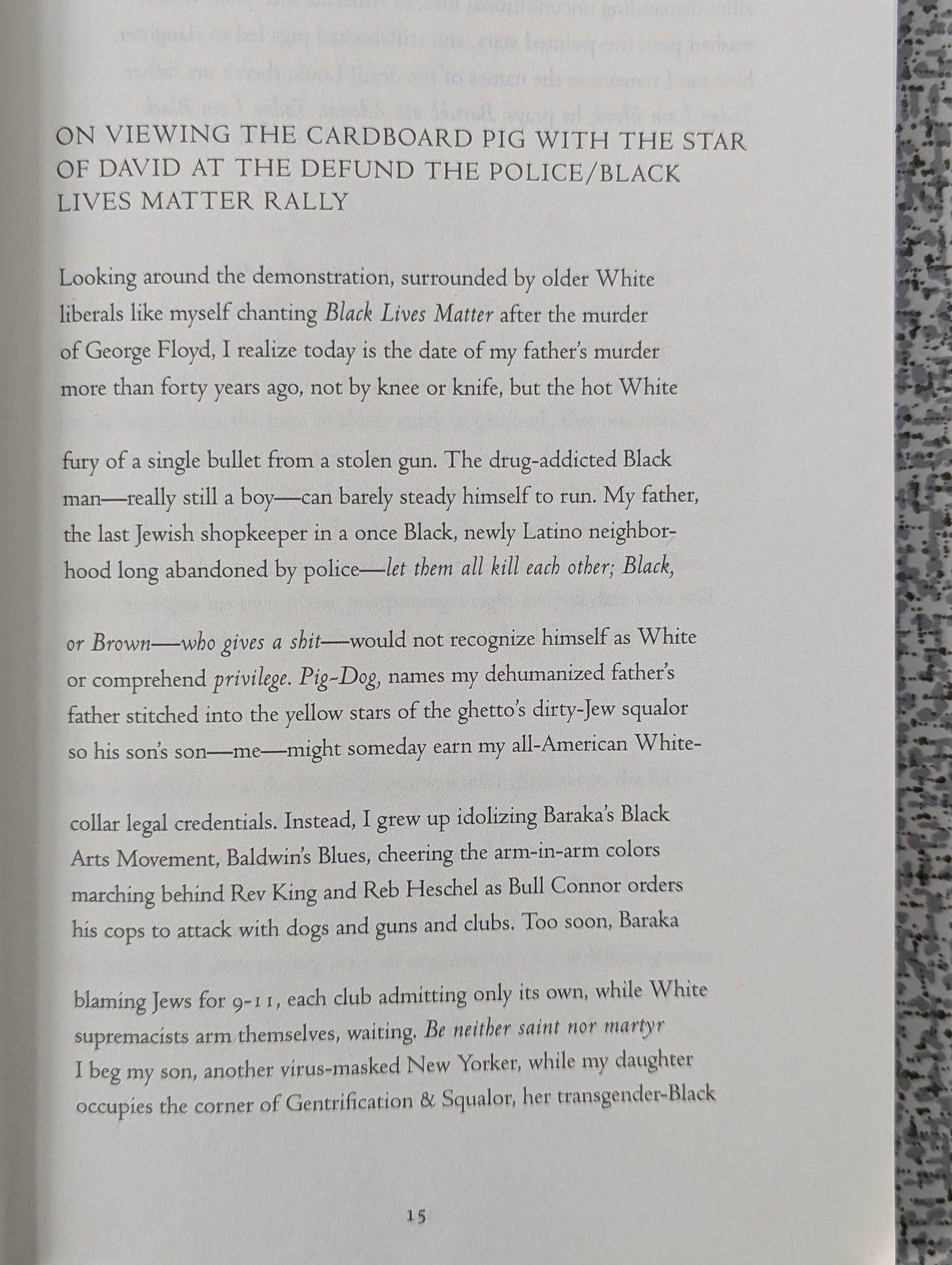

After all, how many poets would title a poem “On Viewing the Cardboard Pig with the Star of David at the Defund the Police/ Black Lives Matter Rally”?

A certain fearlessness is required for that kind of title. But Michelson is about more than just shock. His work is also about care and craft; in the poem below, notice how “Rev King” and “Reb Heschel” are separated by just one letter. How close “Reb” and “Rev” are in this poem, and in key moments in history. It’s a poem I thought about as I came across a photo of Michelson with Georgia’s U.S. Senator, Reverend Raphael Warnock, which he generously shared with me.

Poet Richard Michelson, at right, with U.S. Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock.

It’s a poem that I am thinking about as the Democratic National Convention ends, and the delegates return to their homes—and as people with all kinds of signs are adding hope and fear to our lives.

Wow that second-to-last line. “Look, there’s my father.” And of course, the last line, melding George Floyd, the beginning of a blessing—Barukh ata Adonai, blessed are You o God—and “Today I am Black.”

But look closely at how this poem was crafted.

The first stanza has “White” as the end-words of the first and last lines, then “Black” in the second stanza’s first and last lines, until the rhyme changes to “Black/ Baraka”—for Amiri Baraka—and finally, in the last stanza, with the father saying Today I am Black, the “rhyme” becomes “White” and “Black”. But wait—Michelson always has something deeper, often more disturbing, to contemplate; maybe it’s “White-/washed” and “Black”.

And then there are the pairs Michelson has for lines two and three in each stanza. That pairing starts with murder / murder, moves to father/ neighbor, then father’s/ squalor, then colors/ orders, martyr/daughter, and finally slaughter/father.

Those middle lines are a commentary, all on their own.

Is This a Book of Prayers?

This lifelong commentary on what happened to his father, and its effect on his family, sometimes becomes prayer. God and various rabbis are everywhere in these poems; Michelson imagines God’s bar-mitzvah and praises the rabbis blocking traffic to protest the Muslim ban.

Reading Michelson requires paying attention, because every word matters; it’s not just the end-rhymes, but also the titles and the epigraphs. The poem “Smoke” uses the title as part of the first line and begins “is pouring from God’s computer. Who here will help?” (So if you skimmed over the title, you wouldn’t get it.)

And the poem “Prayer,” which appears early in the book, features this fabulous line, also a question, which I have borrowed for this newsletter’s title—“Are we here to be God’s body,/ or God’s language?”

This is the kind of poetry that rewards re-reading.

It’s very Jewish to reread, and it’s also very Jewish to not read in order, and to insist, on reading the Torah, that ein mukdam u’meuchar ba’Torah—or there is no early and no late in the Torah, which is a way to read outside of normal chronological order.

So I hope it’s okay to mention, in closing, that this collection has two wonderful epigraphs which I am reproducing here, and which explain where the book’s title comes from. As you can see, Michelson invokes Hebrew—with Yehuda Amichai, the great Israeli poet, and Yiddish, with a folk saying, but he also sets the tone of how these major events in history are juxtaposed with ordinary lives. No matter what your political views, there is no doubt that what is happening right now is affecting individuals, just as history always has.

The Power of Names

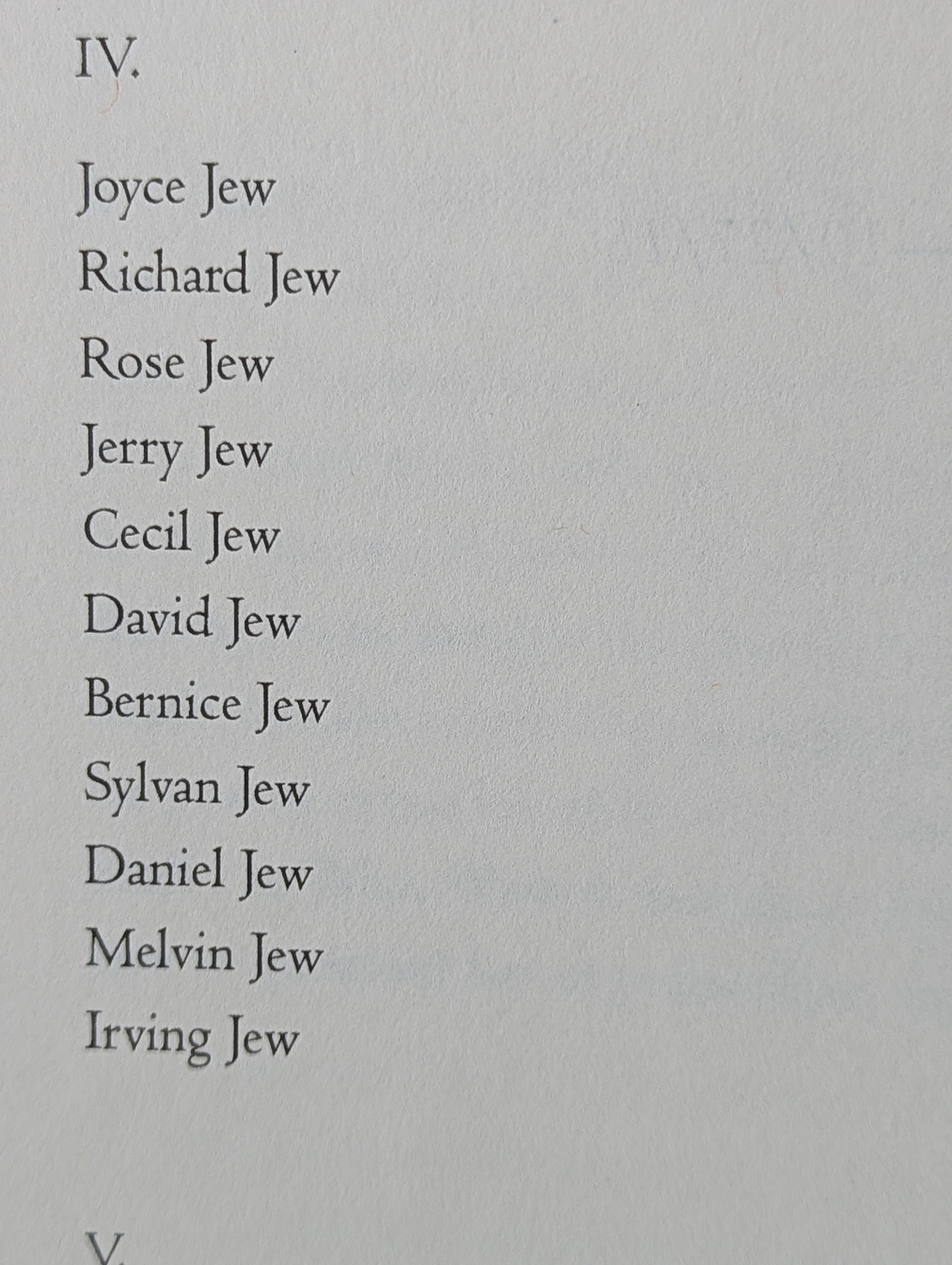

There is one more comment I would like to add. Though I read this book slowly, yet I was still unprepared for the effect of reading the lists of names—such as when Michelson writes the names of the dead from the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting like this, right in the middle of a poem:

I was also deeply moved by “Listening to the Names, Simchat Torah 2020,” in which Michelson memorializes Black men and woman killed by police and weaves them in with the words of the Torah, as recited by his grandfather. It’s another example of that doubling, that expansive vision that was on display in the two poems titled “Life Sentence”. Here is a brief excerpt, its beginning:

As America enters another contentious and—let’s tell the truth—terrifying election season, and as the turmoil around the world continues, I recommend spending time with Michelson’s soul-challenging work. It’s an exploration of the lines between poetry and prayer, and the concept of what a “life sentence” really means, for all of us.

A Review Essay on Kafka

I spent a lot of time over the past few months with an astonishing new translation of Franz Kafka’s stories, recently published by Harvard University Press; my father read a bit of it and insisted that I share the galley with him when I was finished. I wrote about the book for The Forward in a review essay. This new translation of Kafka's stories is a masterpiece – The Forward

September Salon: Richard Michelson & Yehoshua November

If you would like to hear more about the poems in this newsletter, you are in luck!

The next salon, on Sunday, September 29th at 12 EST on Zoom, will feature two terrific poets—Richard Michelson and Yehoshua November, whose much-anticipated third book comes out in September.

And later this fall, stay tuned for a salon with two incredible poet-musicians—Alicia Jo Rabins & Elana Bell. Salons are for paid subscribers of this newsletter, who make continuing it possible. Monthly, annual, and gift subscriptions are available, and your questions and comments at salons are always very welcome!

Book Sale Through August 31st!

I always encourage everyone to purchase books mentioned in this newsletter, or request them from a library, which is free & a great way to support writers.

In August there is a fabulous book sale from Orison Books! You can pre-order The Concealment of Endless Light by Yehoshua November, who will be featured here soon, through August 31st for 50% off if you use the code “justbecause” at checkout. And if you like, you can also order a copy of my debut collection, WOLF LAMB BOMB, also from Orison Books, for 50% off with the same code. I am also partial to the anthology Between Paradise & Earth: Eve Poems. Definitely worth $7.50! Bookstore (orisonbooks.com)

Thank you!!!

I can’t believe On Being and Timelessness is now one year old. Wow!

Thank you to everyone who has supported this newsletter, in all ways! To everyone who has loved this newsletter, shared it, reread it, commented, discovered writers and thinkers from it, made a new friend at a salon, and in some way helped make continuing this rebellion against the “timely” and focus on the “timeless” possible—thank you! You have helped bring this newsletter to readers in 37 countries and counting. I’m excited about continuing and expanding this endeavor in the year ahead.

Shabbat shalom!

************************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I bought this book at the conference! Looking forward to reading and re-reading it with this commentary in mind.

Thank you, Aviya for such a generous reading of my work.