***Hi wonderful readers! A reminder that this Sunday 1/14 at 2 CST is the first Winter Salon—on “Writing & Hope”. Details at the end of the newsletter.***

One of my most prized possessions is a slim black-and-burgundy chapbook by Louise Glück titled October. I bought it when I attended a friend’s wedding in Colorado, at a store that I think was called Poor Richard’s. When I found it on the shelves, I happened to be speaking to our classmate Joshua, a wonderful writer and person who later passed away from lung cancer at age 32. This might be why I associate chapbooks with the most intense moments in life, the ones that matter.

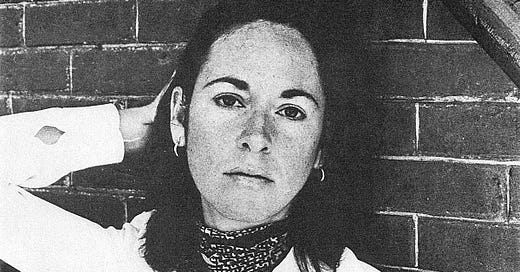

Louise Glück around 1977, from a poster advertising a reading at the Poetry Center at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago

My prized copy of October—purchased years before Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize. It was published by Sarabande in 2004.

A Brief Introduction to Louise Glück

Louise Glück can be described as a poet of the intense moments in life—the thoughts and realizations that matter. She was the author of 14 books of poetry, as well as a wonderful collection of essays that I return to often titled Proofs & Theories.

“Louise Elizabeth Glück was born on April 22, 1943, in New York City and grew up in Woodmere, on the South Shore of Long Island. Her father, Daniel, was a businessman and a frustrated poet who, among other things, helped invent the X-Acto knife,” The New York Times wrote in its obituary.https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/13/books/louise-gluck-dead.html

Louise, as she was known to so many poets, died recently at age 80. I often think her father’s career as one of the inventors of the X-Acto knife can be felt in the searing spareness of her work. It’s there in her devastating line breaks. Throughout her life, she returned with an increasing exactness to subjects like Greek mythology, the natural world, love, and loss.

During her lifetime, she won many awards—the Pulitzer, National Book Award, and then the Nobel Prize. But I think some of her lesser-known and harder-to-find work, like this chapbook, is the most beautiful.

What is a chapbook?

What exactly is a chapbook, anyway?

“It's an ancient form of publishing that is enjoying a renaissance 500 years on with a surge of interest in modern chapbooks,” Helen Carter of The Guardian explained in 2011. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/the-northerner/2011/mar/04/chapbooks-publishing

I don’t know about ancient, but the chapbook as a form is at least several hundred years old.

“The 16th century merriments that became the chapman's stock in trade were historically cheap, crudely made and illustrated using recycled woodcuts,” Carter writes. “Today's chapbooks, which are enjoying a revival along with independent regional publishing, bear little resemblance to the roughly produced books of the past. They are objects of beauty in their own right, with emphasis on original design as well as being a showcase for original writing.”

October has a relatively simple design. I wanted it because of who wrote it. I purchased this chapbook years before Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize. To paraphrase my grandfather, who gave Shai Agnon all the prizes before almost anyone else was reading him, Louise Glück had many prizes with me. Whether or not the poet is world-famous, I keep seeing more and more gorgeous chapbooks. The Guardian agrees that chapbooks can be beautiful, and that people really want them.

“Pamphlet-sized but glossy, and more book than leaflet, they are highly covetable, which partly explains their appeal.” I agree with the word “covetable” very much.

You Can’t Get This Chapbook Easily

October is out of print. A quick look at Amazon shows that I can sell my copy for $92. (I will confess—I paid five dollars.) But it’s also possible to search Google Books and read the first few pages. All in all, October is an 11-page poem. It’s a self-contained world, which is exactly what chapbooks are.

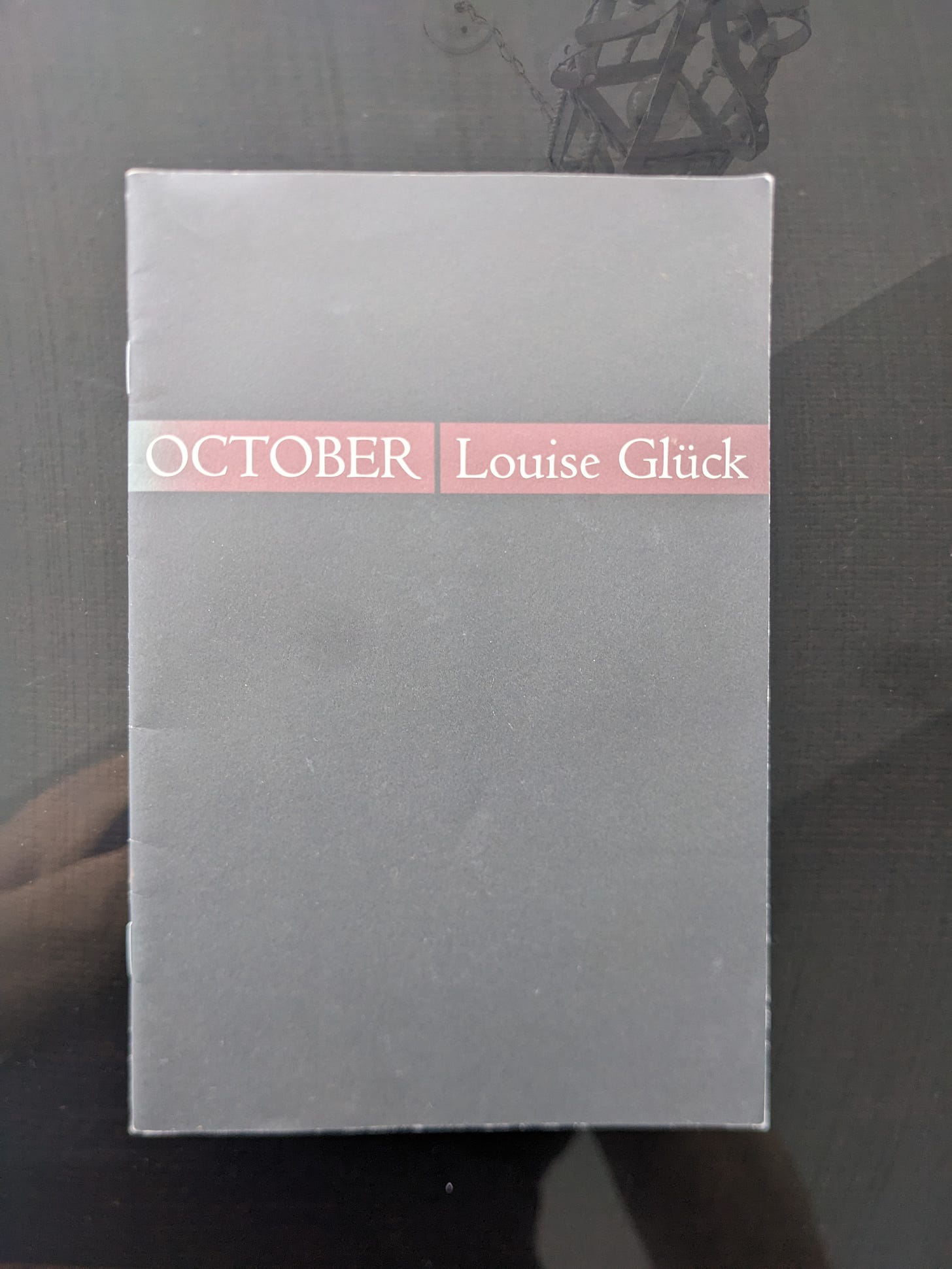

The poem comes in several parts. Here is Part I—what I love about it is how it immediately includes the reader in the conversation of the poem. Though it is titled “October,” in Louise Glück’s hands, it is already winter. And from the first line, I get the feeling that this is a poem that is meant to be reread, throughout the years of a life.

The “Frank” mentioned here is the wonderful poet Frank Bidart—a close friend of hers. I encourage you to read the poem aloud to hear it, and discover the third stanza that way:

I love that second-to-last line—”weren’t we necessary to the earth”. What a question.

Something beautiful about this poem and much of Louise’s work is how it functions in multiple tenses at once. There is the strong present tense, but also a look backward, and then a move into what I think of as the questioning tense at the end.

“What it sounds like can’t change what it is” questions everything, including the role of poetry.

Louise Glück on Snow

With snow falling this week in many parts of the world, here is part III, which begins with snow and then speaks to the world itself.

How can anyone resist that second stanza—"Come to me, said the world”?

The Jewish History of Chapbooks

I certainly did not realize that there was a Jewish connection to chapbooks when I first started reading them.

“Chapbooks are popular literature in pamphlet form formerly hawked by chapmen or peddlers,” Cecil Roth writes in the Encyclopedia Judaica. “Little attention has been paid to these in connection with Hebrew bibliography. Given the fragile nature of things, such flimsy, unbound publications tended to be thumbed out of existence, in many cases leaving no trace.”

I shudder to think of chapbooks that just evaporated. But here comes the Jewish connection hypothesis.

“It is probable, nevertheless, that from the 16th century chapbooks were produced by Jewish printers in Italy and the Balkans and hawked around the local fairs: few, however, have survived. In the 19th and 20th centuries very large numbers of such publications, crudely produced on the cheapest paper, were published in Eastern Europe for hawking by itinerant peddlers.”

Interestingly, some of these were Jewish books. “These would consist in part of seasonal liturgical works (the *Haggadah before Passover , sometimes crudely illustrated; Penitential Prayers (Seliḥot) before New Year; the Book of Lamentations and kinot before the Ninth of *Av ), sometimes accompanied by Yiddish translations for the benefit of the women and the ignorant.”

I must confess that I never thought of the Haggadah as a “chapbook,” but I have certainly seen Haggadot that were flimsy and soft-covered.

The Encylclopedia Judaica, from a post on EBay, where it can often be found.

“Other works produced in this fashion were accounts of the "wonders" of Isaac *Luria or *Israel b. Eliezer Ba'al Shem Tov, books of wondrous stories ("Mayse Bikhlekh"; see *Ma'aseh Book), mainly Yiddish dicta of *hasidic rabbis, model letter books, simple ethical works, and divination handbooks (Sefer Goralot). With the development of Yiddish literature, cheap novels, whether original or in translation, were distributed in the same fashion. Similar works were produced in Ladino in Salonika up to the 20th century, and in Judeo-Arabic both in North Africa and Iraq until the 1940s.”

Interestingly, the Encyclopedia Judaica doesn’t mention chapbooks of Jewish poetry, but the chapbooks I own are almost all poetry chapbooks.

Chapbooks Lead to Events About Them

I think of October as a sort of gateway drug. I didn’t know it when I bought it, but I would soon get very into chapbooks.

On February 9th, I will be moderating a panel at the AWP conference in Kansas City on Friday at 10:35-11:50 a.m. on “Breaking the Rules on Chapbooks: New Approaches to an Old Form.” In preparation, I have been rereading and rereading many chapbooks, and I’ll write about them in the weeks ahead.

If you’ll be at AWP, I’ll also be signing copies of WOLF LAMB BOMB as well as my poetry chapbook Eve and All the Wrong Men at the Yetzirah Poets table on Thursday, February 8th from 3-4 p.m. I’ll have a few copies with me for sale, and a bit of swag—Isaiah-poem magnets designed by the wonderful Lindsay Lusby, featuring poems from WOLF LAMB BOMB.

My Essays on Louise Glück

For more on Louise Gluck, here is a piece I wrote for The Forward when Gluck won the Nobel Prize. Though I did not write the headlines, I like the idea of “a poet of survival”: https://forward.com/culture/456085/a-jewish-poet-of-survival-louise-gluck-is-an-incredibly-timely-nobel/

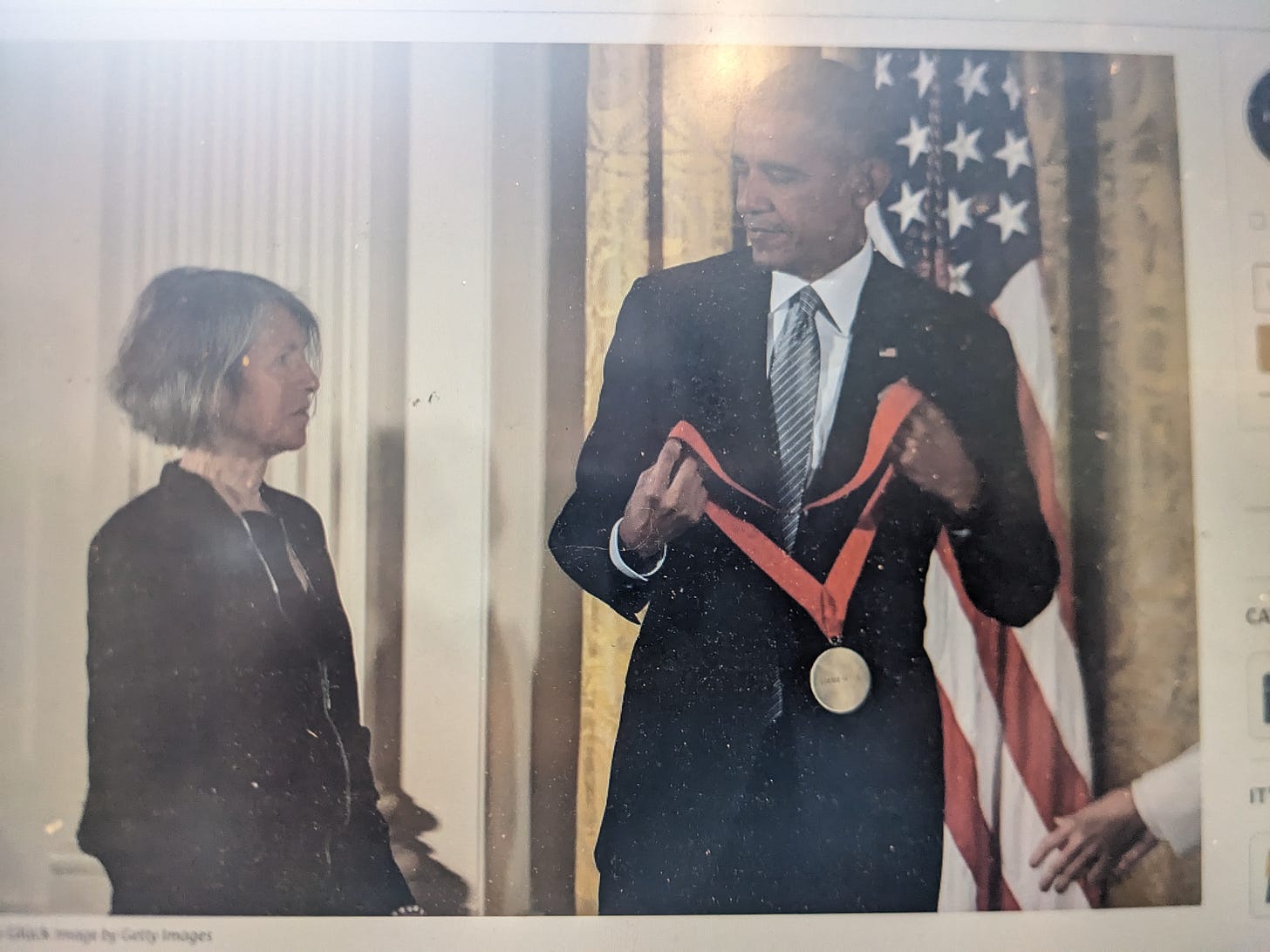

The poet with the president.

Interestingly, I have been writing about Louise Gluck for a long time. One of the first review essays I ever wrote was about her collection Vita Nova. It appeared in the now-defunct The Boston Phoenix, which was a great alternative weekly that had a vibrant book-review section called The Phoenix Literary Supplement.

Here is a screenshot. Incredibly, it’s possible to read it in the online archives. If you want to think about Virgil, Dante, and Louise, leading the way, it’s still there. Page 114.

https://archive.org/details/sim_boston-phoenix_march-26-april-1-1999_28_13

This was one of the first book reviews I ever wrote. I initially said “no”—because I didn’t think someone just starting out should be reviewing Louise Glück. About a month later, the editor came back because everyone else she contacted was afraid to review a book by Glück.

“No one wants to touch this,” she said.

When I discussed the situation with an established and deeply talented poet who knew Greek and Latin well—and was fluent in Italian—she offered to help me with any references to Virgil and Dante in Vita Nova. “It’s awful that people are afraid to review,” she said. That is still true now.

I was grateful for her help so that I would not embarrass myself.

Remembering Joan Acocella

I have to mention that this week, the great essayist and critic Joan Acocella passed away. I love her book Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints. If you have not read that book, read it in her memory. Among other gems, the book includes a beautiful essay on Baryshnikov. “The Soloist,” first appeared in The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/01/19/the-soloist

“Ms. Acocella was often trying to determine what made artists like Mr. Baryshnikov so successful,” Richard Sandomir of The New York Times wrote in Acocella’s obituary. “It was a search that began when she moved to New York City with her husband, Nicholas Acocella, in 1968 and became friendly with a group of young artists who awed her.”

“What will they become?” she recalled thinking about their futures, as she wrote in the introduction to her book “Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints” (2007), a collection of essays and reviews,” Sandomir continued.

This was a question that I was obsessed with around the time I wrote the review of Vita Nova for The Boston Phoenix.

“There are many brilliant artists — they are born every day — but those who end up having sustained artistic careers are not necessarily the most gifted,” she wrote. Rather, she added they were “the ones who combined brilliance with more homely virtues: patience, resilience, courage.”

Courage & Hope—and The First Winter Salon

I think Louise Gluck displayed those three “homely virtues”—patience, resilience, and courage—in her work. Many of the artists Acocella wrote about also had those virtues. And maybe the chapbook, with its “homely” history, has also made it to us with patience, resilience, and courage.

I would add that while those virtues are important, all artists also need hope to go on. This Sunday, the wonderful fiction writer Christine Sneed and I will co-host a winter salon on “Hope and Writing” at 2 p.m. CST for paid subscribers of Christine’s newsletter Bookish or On Being and Timelessness. It will be the first in a series of winter salons for paid subscribers, as I add features to this newsletter and try to build a community of readers.

This salon is a special thank-you to paid subscribers who have made it possible to continue this newsletter and expand it.

I am so moved to share that this newsletter is now read in 31 countries. (Wow!) And so I would welcome your feedback on ideal timing for salons—I will try to vary them to include folks in different parts of the world.

If you have been on the fence about a monthly or annual subscription, or getting a gift subscription for someone you love, consider this an incentive and an invitation. Do join us with a cup of tea or hot chocolate. Paid subscribers can email me or contact Christine for Zoom info—we would love to see you on Sunday, and we can’t wait to discuss hope and writing!

We look forward to your questions & comments on all aspects of writing and hope.

*****************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Louise Gluck’s exploration of trauma touched me deeply at a young age. Her words continuously reverberate through the halls of my own childhood in a profound manner.

I so enjoyed this. I love the poetry of Louise Gluck, although I was not familiar with her chapbook. I have had two chapbooks published and find that the shorter form works so well to really hone in on an idea/theme. I also love your writing and have ordered your newest book.