On Rereading & Renewal

The experience of reading something again often leads to something new.

For many years, I re-read the great Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva’s poems, translated by Elaine Feinstein. At the time, it was the only translation I could find. One day—somewhere in London—I came across a used copy of Feinstein’s poetry, a collection titled Daylight. I was not aware that the translator wrote her own poetry until that minute.

I also had no idea what the translator looked like. As for Tsvetaeva, I had only seen one mysterious photograph, on the book cover.

Marina Tsvetaeva in 1914.

My copy of Daylight by Elaine Feinstein. (Carcanet, 1997).

I picked up Daylight, turned it over, and read the back cover. It quoted The Poetry Book Society selectors:

“Elaine Feinstein, one of the few Jewish poets of her generation working in England, continues to enrich British lyric in her own way….The poems in Daylight distil the store of a working life spent making Eastern Europe, its physical sediments and knowledge of the cold, at home in England….They are quiet, exact, stripped: toughly thoughtful meditations on loved people living and dead.”

As I looked, curious, at Feinstein’s poems, my mind immediately flipped back to a short Tsvetaeva poem from 1916, a window into a world Feinstein introduced me to when I was a student, and Derek Walcott told me I had to read Tsvetaeva and come back to his office and tell him what I thought.

That Tsvetaeva poem wasn’t about toughness—but instead, it was about tenderness. To see the Russian original, click here.

When I returned to Walcott’s office, we discussed the repetition, and the punctuation. We talked about questions and passion. We commiserated—the translator, Feinstein, had not translated all the parts of Tsvetaeva’s magnificent long poem “Poem of the End”. Now, there is far more available in English on Tsvetaeva, such as Ilya Kaminsky and Jean Valentine’s beautiful homage Dark Elderberry Branch: Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva. I’ll probably write about it in this newsletter sometime.

But in any case, I still re-read Tsvetaeva, but now, I also re-read Feinstein. One poet led to another. Or more accurately, translation led me to Feinstein.

Eventually, in those pre-smartphone days, I came across a photo of her.

Elaine Feinstein, poet, translator, novelist, biographer (1930-2019)

There is a lot of Feinstein to read and re-read; she published fifteen books of poetry, including some Selected and Collected, along with fifteen novels, plus radio plays and television dramas. Her five biographies include A Captive Lion: The Life of Marina Tsvetaeva (1987) and Anna of all the Russias (2005), which, as you might guess, is her biography of Anna Akhmatova.

Despite all this, she is rarely (if ever) mentioned in America. I have been thinking about how she is also an example of a poet who openly credits Jewish tradition for her writing, and as Passover approaches, in a time of great trouble and great uncertainty, I have been thinking about that openness.

“My Jewish upbringing was a source of strength,” Feinstein told The Guardian in 1988. “Being Jewish has been so terrible for so many people, but it hasn’t been terrible for me.”

Elaine Feinstein, from her web page.

All four of Feinstein’s grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. “Ever present with her was the knowledge that had her ancestors settled in Germany rather than England, her life might have been very different,” Neil Genzlinger of The New York Times observed in her obituary in The New York Times, which is worth reading as an introduction to her work.

Feinstein was active in British literary life for decades. I was charmed by this paragraph in her website biography, which mentions her contact with other poets, gives a sense of her personal life—and puts her in the context of her time.

And yes, look at those dates:

“She was born in Liverpool , educated in Leicester, and won an Exhibition to read English at Newnham College, Cambridge. She went up in 1949, only a year after the first women were admitted to full membership of the University. After graduating, she read for the Bar in London. She returned to Cambridge with her husband, the molecular biologist Arnold Feinstein, in 1956, and they and their three sons lived in the centre of that city for more than a quarter of century. Writers from across the world including Yevtushenko, Miroslav Holub, Allen Ginsberg and Yehuda Amichai visited them there.”

For some reason, I find myself turning to Feinstein whenever I am about to take a few days off, because her quiet poems often capture everyday moments that we do not always remember to be grateful for. I recently re-read Feinstein as spring break from teaching began, and I thought you might want to participate in that feeling of pausing, just before the rush—or just after—with two Feinstein poems.

And a brief heads-up—the subject of the first is very different from the second. It’s just one example of Feinstein’s different registers.

Behold the Bathroom

There is a beautiful prayer in Hebrew, asher yatzar, that is said after going to the bathroom,expressing gratitude to God for creating the body with wisdom, and giving thanks for all the parts and cracks and hollows of the body that work, but I must say that while I am familiar with the prayer, I almost never come across a poem featuring bathroom time.

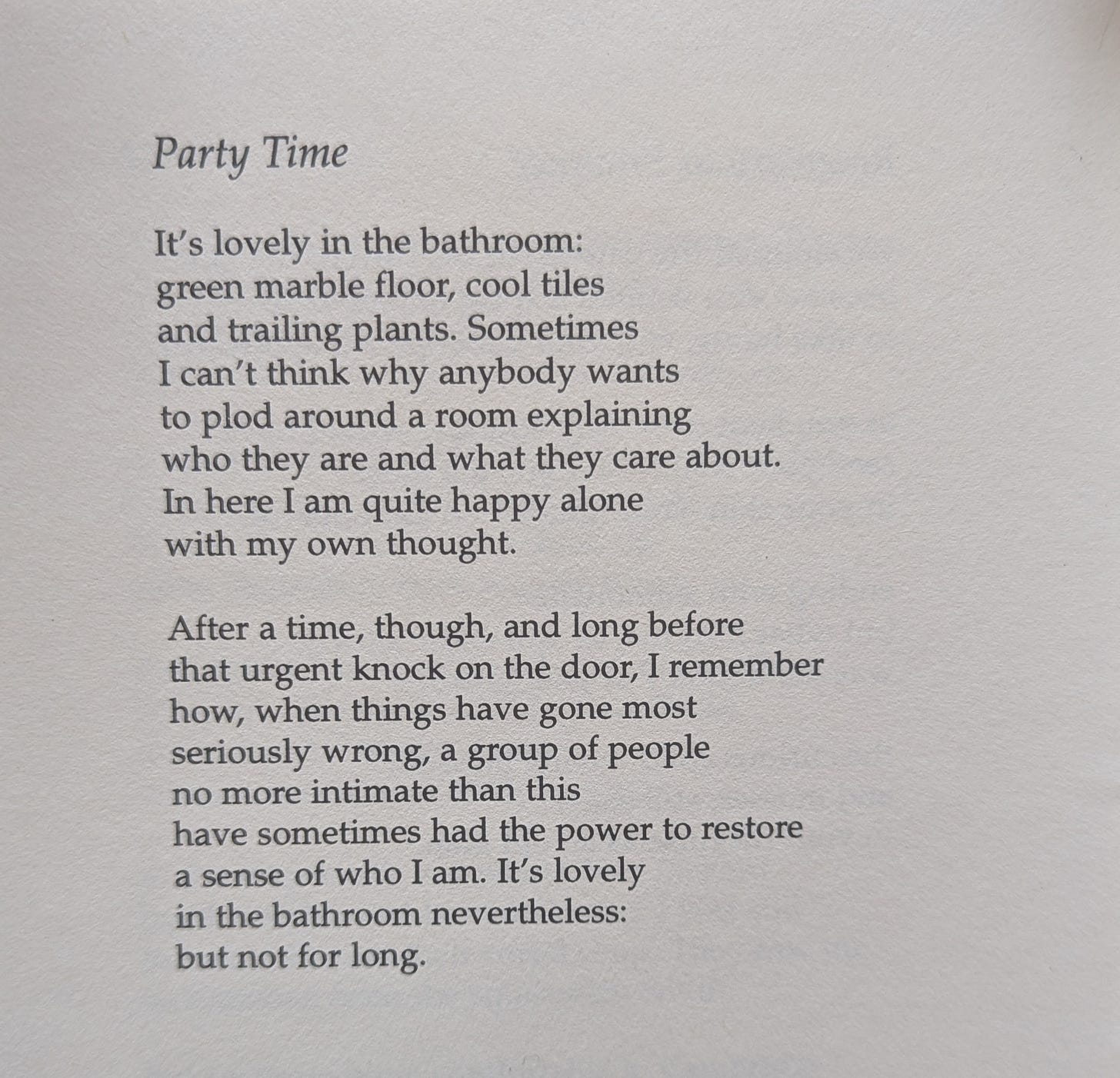

Here is Feinstein’s version, a surprise from the title onward:

That idea that some people “have sometimes had the power to restore/ a sense of who I am” is something I return to, and I also wonder if some people have the power to destroy a sense of who we are. But overall, I love the sense of gratitude in this poem, as well as its acknowledgement of fleeting-ness, all framed by the cheekiness of a bathroom poem in the first place.

And here is a more standard form, a poem of prayer. It’s the last poem in Daylight:

I am always astonished and re-astonished by that simple sentence that starts the last stanza: “God is the wish to live.”

Rereading Isaiah

Speaking of rereading, many readers know that I spent years of my life rereading The Book of Isaiah. I’m delighted to share that I have an essay in the new anthology Smashing the Tablets titled “Isaiah and Power.”

I love the variety of approaches in this book, and I’m thrilled to see this book in the world. It’s in bookstores now.

A Reading Recommendation

I thought of the Poetry Society’s comment—”toughly thoughtful meditations on loved people living and dead” as I read Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s beautiful and unforgettable essay in The New York Times Magazine on her friend’s father, a Holocaust survivor, and on the questions many of us—if we are honest—are feeling now, about the Holocaust, history, contemporary antisemitism, and where, exactly, we are.

I read it and re-read it, because it says so much of what I am feeling, and I think everyone should read it, so here is a gift link. This Is the Holocaust Story I Said I Wouldn't Write

I am very interested in what you think of it—please feel free to comment. And of course, please feel free to let me know what you think of the late Elaine Feinstein’s work, too.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner.

Many of us are preparing for Passover, and the Seder, and of course, the reading of the Haggadah is the ultimate re-reading experience. So much of the Haggadah is beautiful, and so much of it is painful. I wish all of us—whether we celebrate Pesach or not—the pleasures of rereading and renewal, and I hope you discover something unexpected as you read.

********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

What an excellent post! So interesting. I loved it.

Thank you for introducing me to these beautiful poems by a poet I was not familiar with!