It’s always a risk, to say what you mean. When I read a memorable book review, I think of W.H. Auden, a poet I love deeply, who didn’t believe there was a point to negative reviews, or slamming what we might politely call crap. “Bad art is always with us, but any given work of art is always bad in a period way; the particular kind of badness it exhibits will pass away to be succeeded by some other kind,” Auden wrote. “It is unnecessary, therefore, to attack it, because it will perish anyway.”

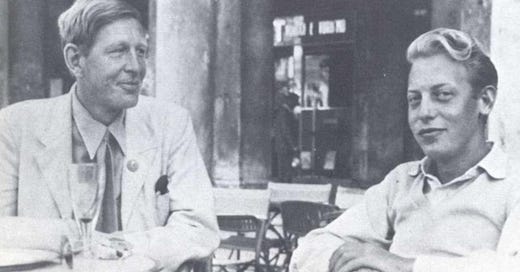

W.H. Auden and his partner Chester Kallman in Venice, 1951.

Auden believed that “the only sensible procedure for a critic is to keep silent about works which he believes to be bad, while at the same time vigorously campaigning for those which he believes to be good, especially if they are being neglected or underestimated by the public,” as he wrote in The Dyer’s Hand.

I believe in the second half of that, for sure—I often write about beautiful work I think would be otherwise neglected or underestimated. And I seem to recall reading that Auden once said that while he did not write negative reviews, he and his partner, Chester, enjoyed reading “catty” reviews. While I can’t remember where I read that, I think “catty” might be a generous description of Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, reviewed by Mary Gaitskill in Bookforum.

I enjoyed this review immensely, and I have reread it many times.

It begins like this. (Brace yourself):

“This is not a book I would normally read; I rarely read mysteries, and the title, Gone Girl, is irritating on its face. I bought it anyway because two friends recommended it with enormous enthusiasm, and because I was curious about its enormous popularity: the millions of copies sold, the impending movie by David Fincher and Reese Witherspoon, the glowing reviews. I found it as irritating as imagined, populated by snarky-cute, pop-culturally twisted voices coming out of characters who seem constructed entirely of “referents” and “signifiers,” and who say things like “Suck it, snobdouche!” The only reason I kept reading was that I’d taken it with me on a long train ride, and it was better than obsessively checking my messages (which is something). As I read, I began to find the thing genuinely frightening. By the time the train ride was over, I felt I was reading something truly sick and dark—and in case you don’t know, I’m supposedly sick and dark.” Mary Gaitskill reviews Gone Girl in Bookforum

Mary Gaitskill at the 2010 Brooklyn Book Festival, about three years before she reviewed Gone Girl. Photo by David Shankbone.

I also loved Stephen King’s review of a biography of Raymond Carver in The New York Times. I can’t believe that fifteen years after I first read it, I still remember King defending Carver’s first wife, Maryann, from her treatment by the biographer Carol Sklenicka, because that kind of thing happens so rarely.

These are my two favorite paragraphs:

“Although Sklenicka exhibits something like awe for Carver the writer, and clearly understands the warping influence alcohol had on his life, she is almost nonjudgmental when it comes to Carver the nasty drunk and ungrateful (not to mention sometimes dangerous) husband. She quotes the novelist Diane Smith (“Letters From Yellowstone”) as saying, “That was a bad generation of men,” and pretty much leaves it at that. When she quotes Maryann calling herself a “literary Cinderella, living in exile for the good of Carver’s career,” the first Mrs. Carver comes across as just another whining ex-wife rather than as the stalwart she undoubtedly was. Ray and Maryann were married for 25 years, and it was during those years that Carver wrote the bulk of his work. His time with the poet Tess Gallagher, the only other significant woman in his life, was less than half that.”

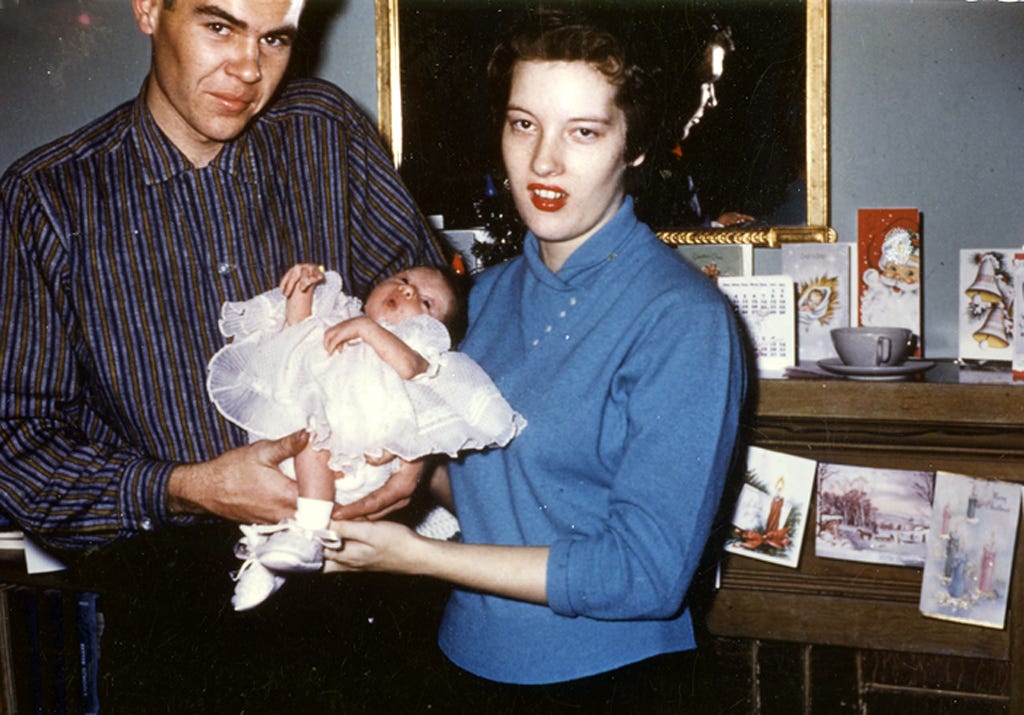

Raymond Carver, Maryann Carver, and their daughter Christine, in 1957.

“But when he died in 1988, the woman who had provided his financial foundation discovered that she had been cut out of sharing the continuing financial rewards of Carver’s popular short-story collections. Carver’s savings alone totaled almost $215,000 at the time of his death; Maryann got about $10,000. Carver’s mother got even less: at age 78, she was living in public housing in Sacramento and eking out a living as a “grandmother aide” in an elementary school. Sklenicka doesn’t call this shabby treatment, but I am happy to do it for her.”

It’s that last sentence that gets me every time. You can read King’s entire masterful review here. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/22/books/review/King-t.html

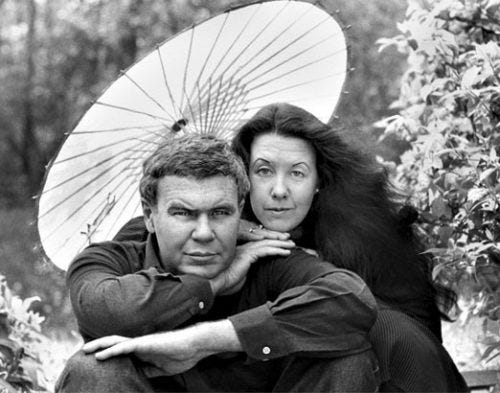

Raymond Carver and Tess Gallagher.

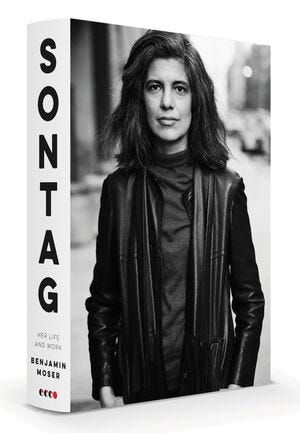

And be sure to treat yourself to reading Vivian Gornick on a biography of Susan Sontag by Benjamin Moser, also in The New York Times. Talk about high standards for a book. This was my favorite paragraph, though it’s hard to choose:

“Benjamin Moser’s biography is a skilled, lively, prodigiously researched book that, in the main, neither whitewashes nor rebukes its subject: It works hard to make the reader see Sontag as the severely complex person she was. But Moser doesn’t love her, and this absence of emotional connection poses a serious problem for his book. A strong, vibrant, even mysterious flow of sympathy must exist between the writer and the subject — however unlovable that subject might be — in order that a remarkable biography be written. And this, I’m afraid, “Sontag” is not.”

Whew. He “doesn’t love her.” Vivian Gornick on Benjamin Moser's biography of Susan Sontag

Vivian Gornick, photographed five years ago, at age 84. Photo: Pari Dukovic https://www.thecut.com/2020/01/vivian-gornicks-the-romance-of-american-communism.html

Interestingly, Moser’s Sontag biography later won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in “distinguished biography, autobiography or memoir”. For a different take on the book from the Pulitzer judges, read here: Pulitzer Citation

Susan Sontag in 1979, photographed by Lynn Gilbert. (Wikipedia)

And now for some personal commentary on reviewing. I have been reviewing books since I was 23 years old, when Derek Walcott made all the students in his graduate poetry workshop promise to review two poetry collections a year, as he did.

I have been doing at least that ever since.

Like everyone who reviews books, I am always drowning in review copies. I cannot possibly read all the books publicists, publishers, and authors send me. When I say “I can’t promise anything, but I will try”—I mean it. Still, I often wish more writers would review books; we need more reviewing, not less, especially by people who know what they are talking about.

But let’s get real.

Reviewing doesn’t pay well, if at all. I found out it doesn’t count toward tenure. It’s high-risk—you could hurt someone’s feelings, and hurt your own career. But it’s an art form, and an important one, and it helps art continue.

One day’s book mail—five books. I snapped this as I started this post.

I thought of this again this Shabbat while reading a review written by one of my favorite writers, Stuart Dybek. (Yes, I am behind on my newspaper reading and read reviews weeks later!) Dybek reviewed a first book, and I remembered how Derek Walcott told me he always reviewed one debut a year. You can imagine that I was thrilled to see that Dybek’s review begins like this:

“The Continental Divide,” Bob Johnson’s debut collection of 14 stories, begins with an epigraph from Jeremiah: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; who can know it?”

“Epigraphs can be forgotten, if read at all, but this one continued to resonate after the tour de force title story that opens the book. As one potent story segued into another, alternative epigraphs started occurring to me. From Blake: “Some are Born to sweet delight/Some are Born to Endless Night.” Johnson’s stories dwell in the latter. From Flannery O’Connor: “She would of been a good woman … if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” That iconic story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” ends with the kind of violence that is a go-to in several of Johnson’s stories. Think Flannery O’Connor meets Quentin Tarantino.” Stuart Dybek reviewing "Continental Divide" by Bob Johnson in The New York Times

This is why I wish great writers would review more often.

I have two other big wishes on the reviewing front. First, I wish readers could figure out a way to support serious reviewing, especially of poetry collections, literature in translation, serious Jewish literature, and other tough-to-place-a-review categories of books, and to make sure reviewers were paid decently for the significant amount of time it takes to do a decent job. Please feel free to post a comment to start a conversation about how we can all support substantive reviewing of books, or write to me if you prefer. I think Substack is one option—but I would love to see more thoughts.

And second, I really do wish that every writer who wrote me to ask about a review of their book would keep the promise I made to Derek Walcott all those years ago—"review two books a year to keep the conversation going. Then we’ll talk.”

Wishing you many happy hours of reading, along with the joy of coming across a truly memorable review!

Upcoming Salon March 16th

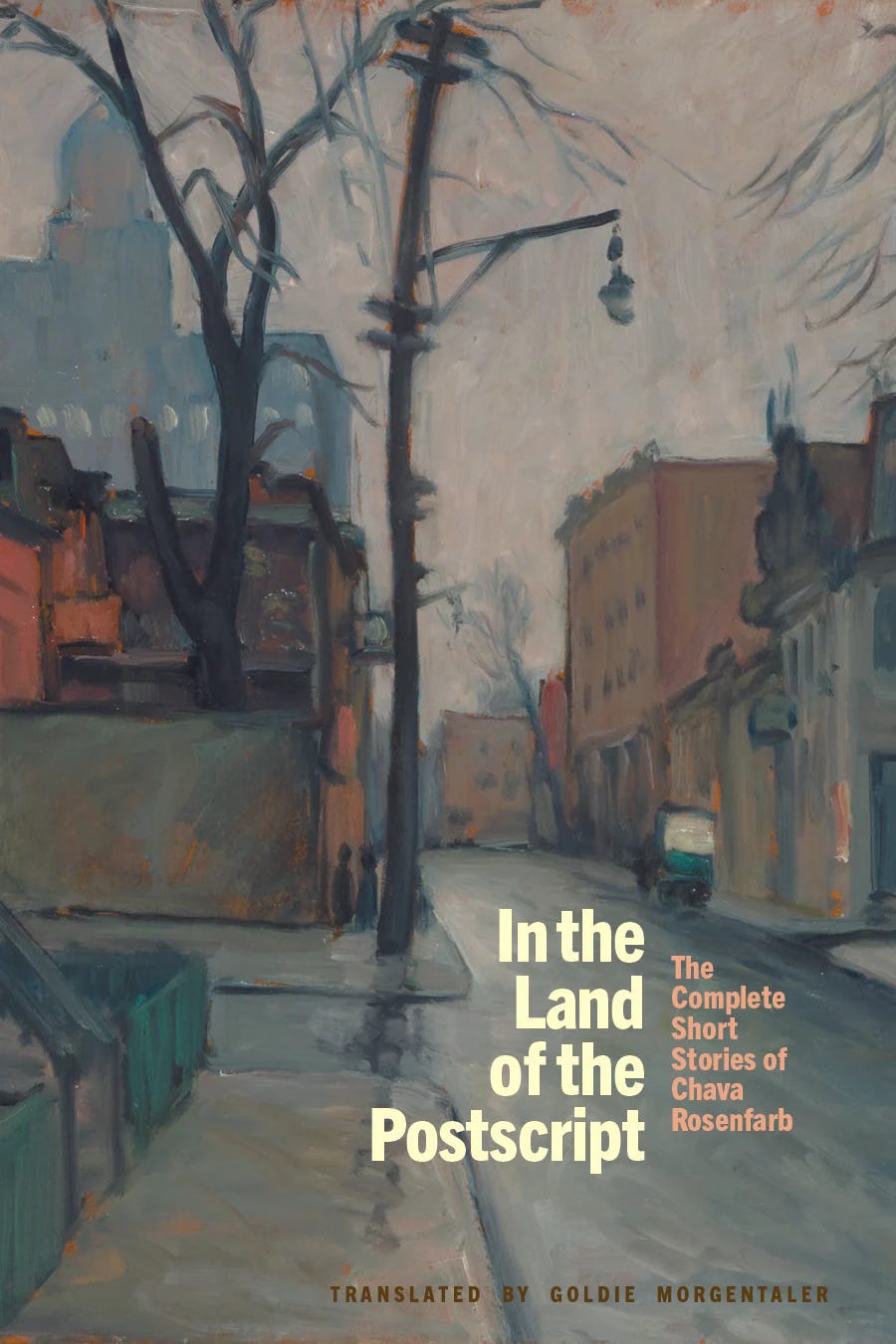

I’m really excited to spotlight the great Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb, who would be 102 if she were still alive, along with two incredible women who are bringing her work to life in English—Goldie Morgentaler and Kathryn Hellerstein. Rosenfarb is an example of a writer I wish would have been reviewed more in mainstream publications. (I’ll send out a newsletter with Rosenfarb tidbits to give you a sense.)

We’ll walk through one of Rosenfarb’s most haunting stories, about a kapo and the one woman whose life she saved—and as always, I will try to understand how this work of art was made. I thought about this story for months; I started reading it before October 7th, and it stayed in my head during the terrible period after that.

Paid subscribers have received a PDF of “Edgia’s Revenge,” and if you sign up at least 30 minutes before the salon starts, you’ll receive it too. You can also purchase Rosenfarb’s Collected Stories in English, or request it from a library. National Yiddish Book Center bookstore link for Rosenfarb's stories

A bit more abour the salon’s distinguished guests:

Goldie Morgentaler won another Canadian Jewish Literary Award in October 2024 for her translation of the stories in In the Land of the Postscript, including “Edgia’s Revenge”. She is Rosenfarb’s daughter and her translator, and a retired professor of English, based in Canada.

Kathryn Hellerstein is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and an authority on women’s writing in Yiddish. She is a translator and poet as well as a scholar.

Salons are for paid subscribers who help make this endeavor possible. My hope is to offer a chance to encounter writers, translators, and thinkers who deserve more attention, and to give readers a chance to ask questions.

Each salon is exactly one hour long. Monthly, annual, and gift subscriptions are available, and include access to recordings of past salons. Each Founding Member will receive a 30-minute Discuss Any Writing Issue session on Zoom--for yourself or a writer friend.

Hope to see you March 16th at 5 EST/ 4 CST!

*************************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writin with depth.

Aviya, I agree with you that more of us need to write reviews--I write about one a month, mostly for Rhino Poetry. And I also agree with Auden, though I didn't know what he'd said about reviews. Especially for poetry, so little read in our country though there are too many collections published each year for anyone to read them all, it makes no sense to publish a review that cuts a poet down. Lift up the books that are satisfying to read, even if (we are all human) flawed. In the case of Gone Girl, which I feel no temptation to read, I can see writing a catty review if it's deserved, since it has gotten so much positive attention. But that's a very different case!

Aviya -- this is such a terrific post; thank you. I loved the overall idiosyncratic humanity of these reviewers -- from Auden's excellent observation that bad work will die on its own accord; to the basic decency of Stephen King's zinger of a last sentence. Years before Claire Dederer's Monsters, he was making a similar point that the life *does* matter; and that that too is part of the record. Anyhow -- thank you for the powerful reminder that if we want a flourishing literary ecosphere we all have to pony up with out water buckets ;)