One Poem for Yom HaShoah

The great Avrom Sutzkever on neighbors, philosophies, and the urge to survive.

What is there to say on Yom HaShoah? Already, so many, near and far, don’t want to hear about it. I have tried to teach books about the Shoah a few times in recent years; it hasn’t gone well. In the silence, in the solemnity, in the statistics on the rising percentage of people who don’t know basic facts about the Holocaust—or who think it was exaggerated—I find myself returning to the great Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, who survived the Shoah in Vilna’s ghetto and the surrounding forests, and who for a time was hidden by a Polish woman.

I want to share a single Sutzkever poem about neighbors.

“The theme of neighborliness appears frequently in the work of the Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, particularly in Poems from My Diary, the 1985 collection from which the following poem is taken,” Maia Evrona writes in her excellent translator’s note. I think Evrona’s work on Sutzkever deserves more attention.

In Vilna, Evrona reminds us, about 40,000 Jews were forced into two ghettos, yet Jewish cultural activities did not stop, despite the harsh conditions. Most of the ghetto’s residents were slaughtered in Ponar, a forest just outside Vilna. Only a few hundred Jews survived.

And of course, there were the neighbors.

“While the Ghetto’s walls cut Jews off from Vilna’s Lithuanian and Polish residents, Jews who lived on its borders could hear their Lithuanian neighbors singing the Horst Wessel Lied — the anthem of the Nazi party. The murders in Ponar were carried out largely by Lithuanian volunteers. Sutzkever, meanwhile, had been hidden at the beginning of the occupation by a Polish woman, and prior to the war, had been passionate about Jewish-Polish co-existence,” Evrona writes.

You can hear some of that in the poem below. But Evrona points out that the neighbor issue persisted after the Shoah ended, and after Sutzkever made his way to Israel; you can hear some of that here too.

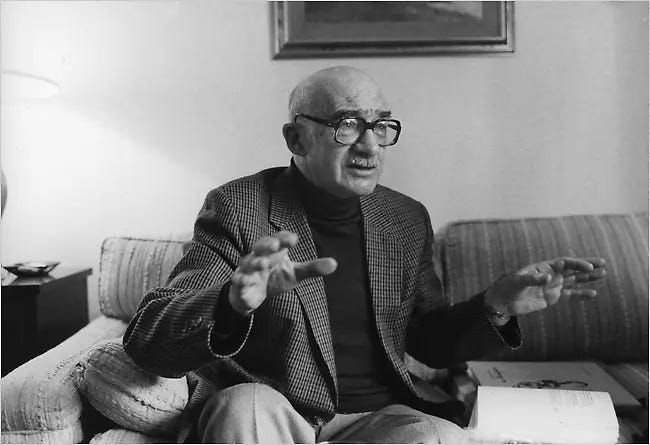

Sutzkever later in life. This photo appeared in his New York Times obituary, where he was described as a “poet and partisan.”

“Israelis who witnessed the influx of Holocaust survivors after 1945, along with Americans who witnessed a similar inflow into New York, have admitted to a repressed disgust for survivors and their experiences,” Evrona writes.

In the young Israel, Hebrew reigned, and Yiddish was being pushed down. Few cared that Sutzkever was probably the greatest Yiddish poet of the 20th century.

“For many Holocaust survivors, the most difficult period came after liberation, when they attempted to return to mundane life, after years of clawing desperately at survival. While Sutzkever wrote this poem in the 1980s, years after his own liberation, and despite experiencing ongoing war and terror as an Israeli, it seems this post-traumatic struggle was still on his mind, rapping at his temples in the shape of his former neighbor, whose ultimate fate he opts not to disclose.”

The first stanza captures how the Shoah never left Sutzkever’s poetry. You can read the Yiddish original here: Avrom Sutzkever on his neighbor from the ghetto. Maia Evrona’s translation appears below; it originally appeared in Waxwing.

MY NEIGHBOR FROM THE GHETTO

My neighbor from the ghetto raps at my temples

Just like then, when a swarm of blonde locusts

invaded my mother city

and mowed it down:

“Oh my dear brother, life is of no importance to me,

what I want is to survive, that is everything.”

Now, as my temples tap out that same verse, already

for the umpteenth time, ever more mysteriously

what was said demands its due within me:

To survive.

Of course, I also wanted to survive,

I wanted, and still want to survive.

To survive — what sort of thing and whom?

To survive terror? To survive

some someone who shows unkindness to me?

And perhaps to survive death altogether?

It seems very little, seems very little …

**********

What can anyone say in response to a survivor questioning what survival means?

Sutzkever tries to answer his own question. And I often feel something hidden, something mysterious in Sutzkever’s work—whether it is poetry or prose, and even if it tries to answer its own questions. Somehow this year that ending—“it seems very little, seems very little”— feels like something both hidden and seen.

*************************************************************************************************************

Hope you found this newsletter meaningful. Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

The only thing to say is to keep remembering and teaching about the Shoah, whether or not this moment's students want to hear. https://www.picciolettabarca.com/posts/to-say-a-prayer-by-abraham-sutzkever

Poetry is shared as our felt human being is universal. Translation also felt poetic art.