Out of Print But Not Out of Mind

How can books this beautiful be unavailable?

I tried to assign two of my all-time favorite books for my fall courses, and I could not, because both were now unavailable. How is it that Hopper by Mark Strand, which is a slim book about Hopper’s great paintings—or more accurately, the great feelings of Hopper’s great paintings—is now impossible to buy for less than $73?

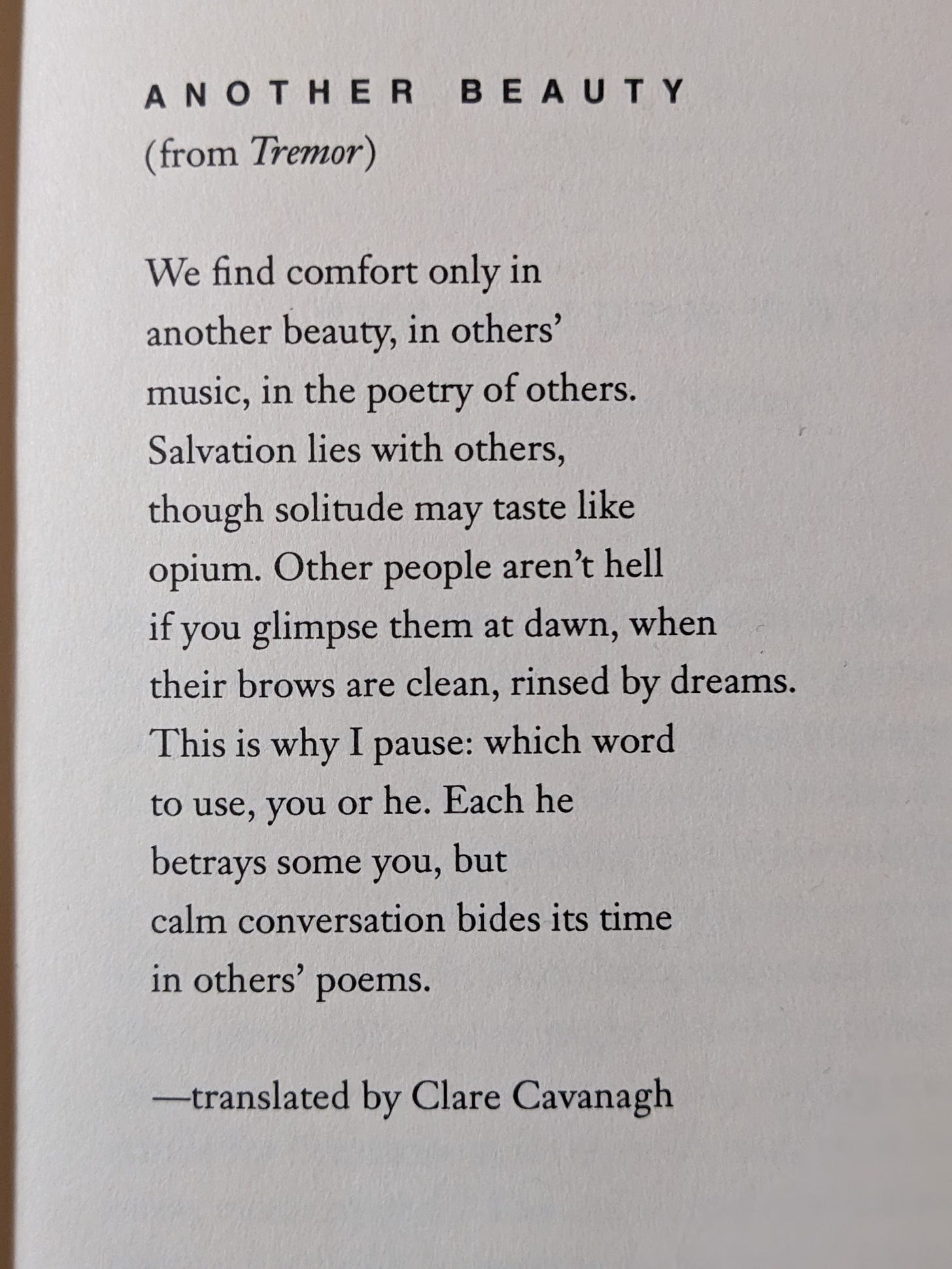

And what about Another Beauty by Adam Zagajewski, translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh, with a foreword by Susan Sontag? I don’t know anyone who has read Another Beauty who doesn’t also reread it every year or so. It’s almost impossible to stop yourself from rereading scenes from the young Zagajewski’s Kraków, and feeling a poet become a poet. I thrill over his depictions of the landlady, the maid, and other characters of a bygone era in a now-transformed Poland.

I imagine Sontag once did, too.

Susan Sontag in 1979. Photograph by Lynn Gilbert via Wikimedia commons.

It’s also worth noting that in the end, prizes and critical acclaim and sheer celebrity can’t keep a book in print. Mark Strand won a Pulitzer, and served as the Poet Laureate of the United States; Zagajewski won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the Griffin Poetry Prize Lifetime Recognition Award, and was widely considered one of the world’s major poets. Sontag’s celebrity status, intellectual heft and famous hair, and the publisher’s hopes that the Sontag stamp mattered, couldn’t keep a book in print either.

I want to highlight a few gorgeous moments in these books, in the hopes of bringing their paperback versions back to classrooms and living rooms.

Hopper by Mark Strand

I have always loved how Professor Strand, which is how I always think of him—he was my teacher when I was an undergrad—describes what Hopper is not in his preface. He’s warning the reader. This technique is a bit like what Louise Glück does in her wonderful collection of essays, Proofs & Theories, where she writes about what she does not agree with and does not believe. Here is an example:

“Hopper’s paintings are not social documents, nor are they allegories of unhappiness or of other conditions that can be applied with equal imprecision to the psychological makeup of Americans,” Strand writes. This is a poet and painter talking back to art historians.

Mark Strand, as he looked about the time he was my teacher.

I especially love that phrase, “equal imprecision.” It’s precise and brilliant and funny at the same time, like Strand was. “It is my contention that Hopper’s paintings transcend the appearance of actuality and locate the viewer in a virtual space where the influence and availability of feelings predominate,” Strand writes. “My reading of that space is the subject of this book.”

I love the idea of reading a space.

Rediscovering Hopper with Mark Strand

This is a book about how it feels to look at Hopper paintings. But it is also about time, and the passage of it.

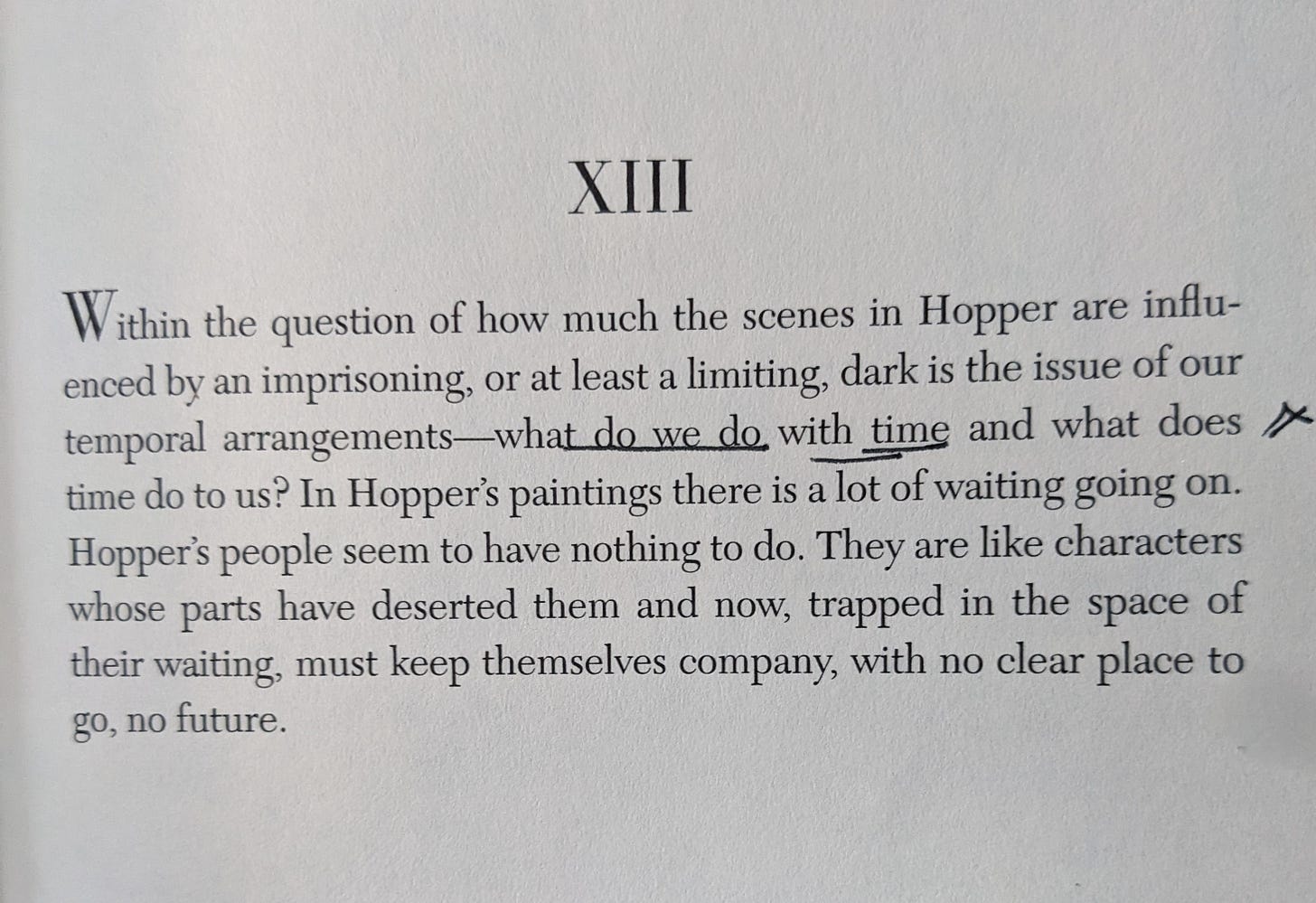

Most of the short prose in this book is directly tied to a painting but in a few moments, there is just text—presented without an image. Usually, those moments directly address the subject of time.

“What do we do with time and what does time do to us?” This is Hopper’s subject but also Professor Strand’s great subject, explored in poem after poem. I find the sad fact that it is now impossible to buy this book in an affordable paper format another example of what time does. And Strand is exactly right, of course; Hopper’s paintings are all about waiting, which is just time, passing. And maybe now, readers have to wait to find this book—stepping into the Hopper experience in that key way.

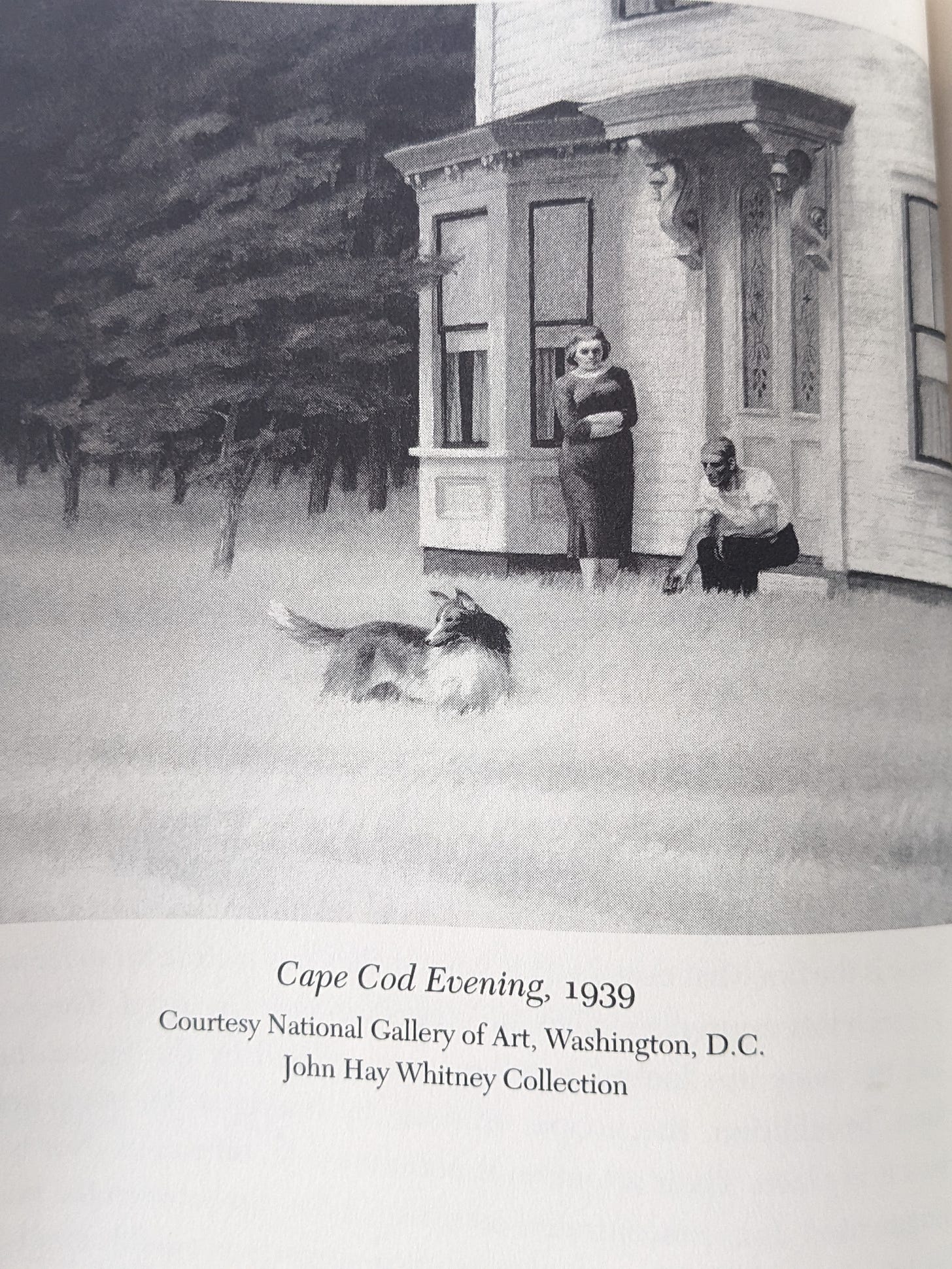

If you find the hardcover, you’ll have Hopper paintings in color. The paperback version has black-and-whites, like this image of Cape Cod Evening.

Cape Cod Evening by Edward Hopper.

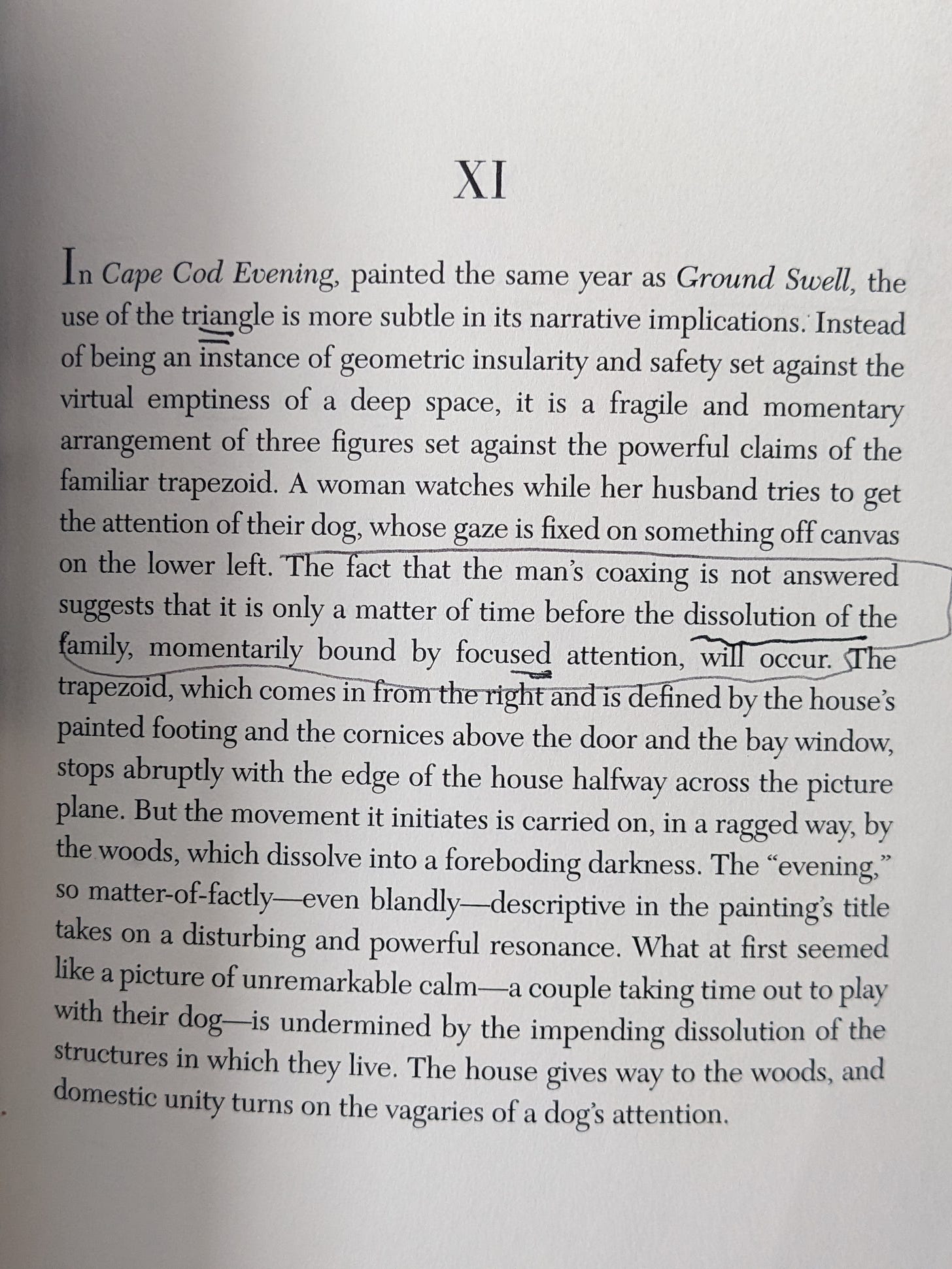

I do not seem to have any copies of Hopper without markings in them. Here, on page 25, XI, writing about Cape Cod Evening, doing his thing of writing about a painting in a single paragraph, Strand as usual notices what does not happen as well as what does. I boxed that section way back when, and I return to it now.

“The fact that the man’s coaxing is not answered suggests that it is only a matter of itme before the dissolution of the family, momentarily bound by focused attention, will occur.”

There it is, time, again. And because Professor Strand started out as a painter, he always explains the geometric happenings. “It is a fragile and momentary arrangement of three figures set against the powerful claims of the familiar trapezoid,” he tells us about Cape Cod Evening.

This is a great book to carry when seeing Hopper paintings in person, when it’s easier to make out the trapezoids and the triangles. And for all those who miss him, commenting on paintings or poetry or the world, here is Mark Strand reading a poem about another time for the PBS News Hour:

For Further Reading:

The New York Times on a publisher focusing on out-of-print books

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/24/books/old-books-out-of-print-open-road.html

Mark Strand page at the Library of Congress—with links to readings

Another Beauty by Adam Zagajewski

These two books—different as they are—pair well together. And maybe it takes Susan Sontag to explain why.

“All writing is a species of remembering,” Susan Sontag writes in her introduction to Another Beauty, whose title comes from a poem by Zagajewki and translated by Clare Cavanagh.

A few sentences later, Sontag adds: “The recovery of memory of course, is an ethical obligation: the obligation to persist in the effort to apprehend the truth.”

I happen to have a special love for prose by poets. And I agree with Sontag that this is a book about memory, and that yes, there is an ethical obligation to remember. But to me, what’s fabulous about Zagajewski’s prose is his skill at characterization—something we might associate with a fiction writer. I love the early passages in this book, where he describes the power struggle between the landlady and the maid, and offers unforgettable portraits of each. Here is Zagajewski describing his landlady, Mrs. C.:

“Mrs. C was preoccupied with her historical mission, with the defense of her own social position, the defense of feudalism in a hostile Communist environment. It was taboo to touch a broom, peel potatoes, wash the floor, make dinner. Such seemingly inconsequential actions could lead to only one thing: the annihilation of her higher substance, the substance that was her greatest and—why beat around the bush?—only treasure. If she were to make herself a soft-boiled egg or fry a schnitzel, then the dignity of an entire era would collapse with a crash, the Middle Ages would finally grind to a halt.”

Like Strand, Zagajewski’s real subject is time—or in Strand’s words, “what do we do with time and what does time do to us?”

Zagajewski next paragraph offers another unforgettable portrait—this time of Helena, the maid:

I know there are lots of markings in the image above—can’t help myself, and I can’t buy another copy easily—so I am typing out some of my favorite Zagajewski sentences from the paragraph above, which is frankly its own education.

“Fortunately, there was someone to wash the windows and floors and do the shopping, make lunch and dinner. Helena, the maid, the servant, the serf. Helena got up every day at 4 a.m. and took the early streetcar—full of desperadoes with eyes red from exhaustion—in to work. She works as a janitor in the city’s center for rat control and perhaps as a result she herself looked a little like a rat: she had a narrow snout a straight nose, and small, bright eyes. She was short and deft, restless and meddlesome. No one ever did battle for this Helen beneath the walls of Troy.”

And who can resist reading this sentence?"

“Mrs. C handed down instructions, managed the expenses, and like any minister of finance, complained about costs and Helena’s unconscionable overspending.”

And so it continues. I could read about the landlady and the maid forever.

Evoking the Vanished

Of course the vanished and murdered Jews of Kraków, one of the great Jewish communities before the Holocaust, cast shadows over Zagajewski’s memories of his student days and youth in that city. Of course Mrs. C. and Helena were around when the Jews disappeared. Time marks every single character Zagajewski writes about, just as it marks all of us.

Adam Zagajewski

“To recover a memory—to secure a truth—is a supreme touchstone of value in Another Beauty,” Sontag writes in her introduction. I find it fascinating to look at which Zagajewski passages Sontag was drawn to.

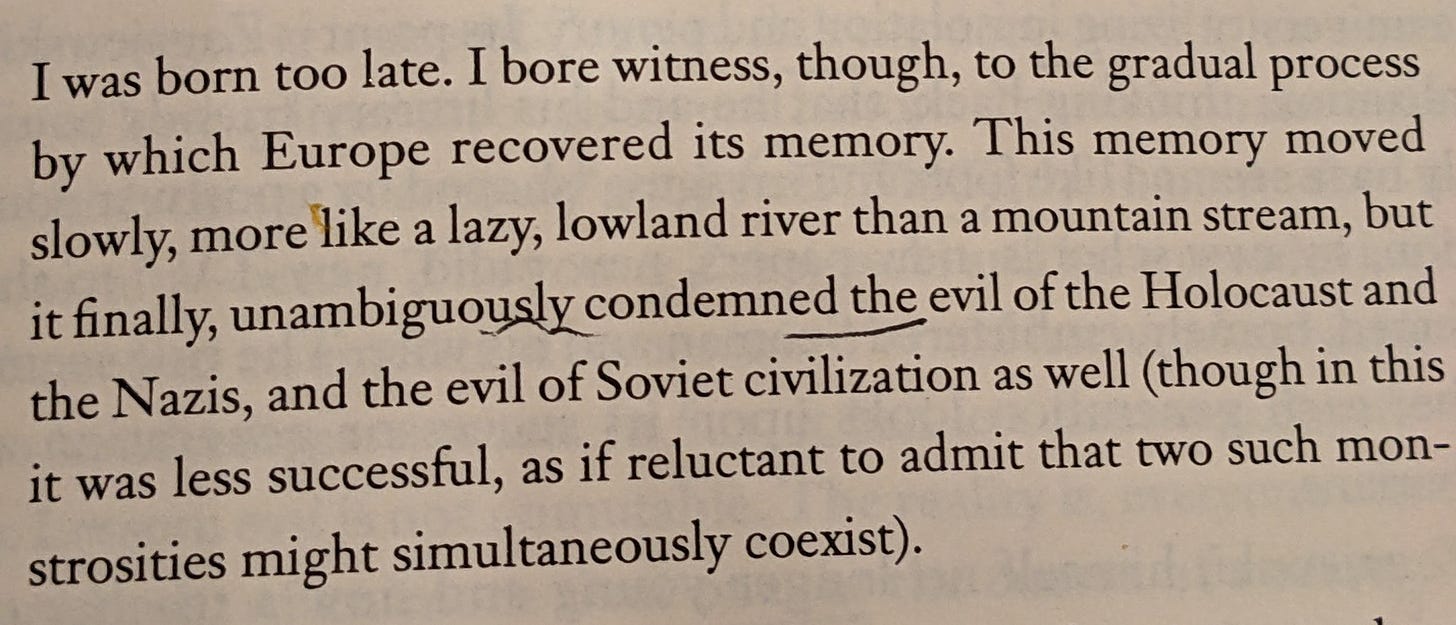

“I didn’t witness the extermination of the Jews,” Zagajewski writes, because he was born too late. Sontag reminds us that Zagajewski grew up in the formerly German, now Polish town of Gliwice, located thirty miles from Auschwitz. And this is the Zagajewski passage from Another Beauty that she chose to include in her preface:

“I was born too late”— he was born in October 1945.

The end of this passage haunts me. I think many of us fear that we are nearing a time when multiple “monstrosities might simultaneously co-exist.” But what of memory? Has it truly unambiguously condemned evil?

And if it did once, is it enough now?

I want to believe in Sontag’s belief in the important work of remembering, of securing a truth. But in both Sontag and Zagajewski, I can hear a time, a few short decades ago, when it seemed that everyone agreed on “unambiguously” condemning the Nazis and the evils of Stalin. Maybe that time is “out of print” these days, like so much else. But maybe Sontag is right; we still must “recover a memory” and “secure a truth”.

Reviving Out-of-Print Books

And maybe part of that is reviving out-of-print books by giants of the page. There always seem to be more of them than any of us expect. They are, I think, essential links to time, and what time does to us.

What are your favorite out-of-print or impossible-to-find books? This is what the comment section was made for! And I would love to know if you have your own version of Strand and Zagajewski—the “I-can’t-believe-it’s-not-in-print” blues.

And last but not least, writing this newsletter made me miss Professor Strand. Here is an essay I wrote shortly after he died, about being his student. Among many other things, he taught me to read translations, to read the world. To me, and to so many of his students, he is always in print. And I suspect the same is true for anyone who was lucky enough to study with Adam Zagajewski. If that was you, please leave a comment, too. I would love to hear about what that was like.

“I Am Old and I Know” — my TriQuarterly essay on being Mark Strand’s student

https://www.triquarterly.org/i-am-old-and-i-know

****************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I participated in a mini-workshop with Adam Zagajewski at George Mason University back in the 80's. C. K. Williams, his poet friend, was teaching there and invited him in for the workshop and a reading. I think I have all his books, spoke to him after the reading but can't remember (!) anything he said. I didn't know about his prose book but did find it online for about $20 from ABE Books. You might want to check it out. I heard Strand read at the Library of Congress, have many of his books as well. I'm going to check and see if I have the Hopper; rings a bell. In Zagajewski's last book there's a poem about his visiting Charlie (Williams) when he was dying; they were friends for some 30 years I believe. Very beautiful and sad. I think Z. lived maybe five years more. Hard to lose all three.

Aviya, your Triquarterly essay was very moving and made me want to read every poet you mentioned (and their prose and all the works of their friends and enemies).