Poetry as Prayer

For Rosh Hashanah, this newsletter's first-ever guest essay, by poet & musician Elana Bell.

In this year like no other, many of us are coming to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur as changed people.

And I have been thinking, throughout the past year, and more intensely over the past few weeks and months, that maybe it is time for new perspectives on prayer.

I have long admired the poetry of Elana Bell, who is also an accomplished musician, and I finally had the chance to meet her this summer in Asheville, NC, at the Yetzirah Jewish Poetry conference. I can say with a whole heart that I was waiting to hear what her voice sounded like, because I so wanted to hear her poems out loud—and then she surprised me by singing. If you haven’t heard her sing, you are missing out.

She also surprised me by talking about prayer.

Poet and musician Elana Bell. (photo credit: Hallie Easley)

As I listened to Elana speak about poetry as prayer, I knew I wanted to make sure more people heard what she had to say.

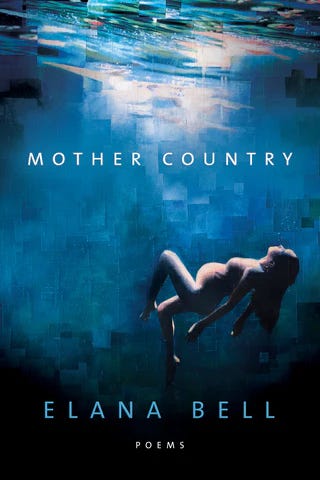

Elana graciously expanded her comments in a special essay for this newsletter. At the end, you will find one beautiful poem of Elana’s that is also a prayer. Elana is the author of two books of poems—Eyes, Stones, winner of the 2011 Walt Whitman award of the Academy of American Poets, and Mother Country, published by BOA Editions in 2020. She teaches poetry to the first-year drama students at the Juilliard School.

I hope you will be as moved as I was, and continue to be. And I look forward to hosting Elana and the wonderful poet-musician Alicia Jo Rabins at an upcoming salon focusing on poet-musicians. Alicia’s gorgeous poem “Love in the Time of Companies” was featured in a previous newsletter—in case you missed it, do check it out! Alicia Jo Rabins poem in a new anthology of Jewish poetry

Shana tova!

********************************************************************************************************

Poetry As Prayer

An Essay by Elana Bell

Truthfully, I think of all poetry as a kind of prayer.

What poetry requires of us, in both the reading and the writing of it, is a deep presence, which I experience as a way of praying.

In Judaism there are four major categories of prayer: there are prayers of praise, prayers of thanks, prayers of confession, and prayers of supplication—where we are asking God, begging sometimes—for something we desperately want or need.

Poems often take the form of gratitude or praise. As poets (and as those who pray), we often look to the natural world to evoke our sense of wonder or the depth of our gratitude for the gift of getting to participate in God’s creation.

One poet I think does this so exquisitely is Mary Oliver, especially in her poem “The Summer Day”.

THE SUMMER DAY

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

Though she claims that she “doesn’t know exactly what a prayer is” I experience this poem not only as a prayer in and of itself, but as instructions on a way of praying. Though Oliver is not Jewish, it feels like she is in direct conversation with Rebbe Nachman, who has a prayer for nature so related to what she has written, that feels like it might be a directive she has followed, or perhaps another strand in the same braid.

This version of Rebbe Nachman’s prayer was translated by Rabbi Shamai Kanter, alav hashalom, father of newsletter reader Rabbi Elana Kanter:

Grant me the ability to be alone; may it be my custom to go outdoors each day among the trees and grass - among all growing things and there may I be alone, and enter into prayer, to talk with the One to whom I belong. May I express there everything in my heart and may all the foliage of the field - all grasses, trees, and plants - awake at my coming, to send the powers of their life into the words of my prayer so that my prayer and speech are made whole through the life and spirit of all growing things, which are made as one by their transcendent Source. May I then pour out the words of my heart before your Presence like water, O L-rd, and lift up my hands to You in worship, on my behalf, and that of my children! [1]

We also have several Brachot that are recited upon seeing the large-scale wonders of nature, such as mountains, hills, deserts, seas, long rivers, lightning, and the sky in its purity:

Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech haolam, oseh maasei v'reishit.

We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, who makes the works of creation.

Then we have ones we recite on seeing the small-scale wonders of nature, such as beautiful trees, animals, and people, wonders of the sort Oliver and Rebbe Nachman are speaking of:

Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu melech haolam, shekacha lo beolamo.

We praise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the universe, that such as these are in Your world.

In this way poetry and prayer become almost interchangeable.

The other kind of poem as prayer that I want to bring forth is one of supplication, a calling out to God.

When I think of this kind of prayer, I immediately I think of David and the psalms, which I read as poem-prayers. For example, in Psalm 121 Davis says,“I lift my eyes to the mountain, from where will my help come? My help will come from the Lord…” It is both a personal prayer and a prayer that can be spoken by anyone who needs to trust in something larger than themselves.

The Hashkivenu prayer, composed by fourth century Talmudic Rabbis, says: “Lie us down, Adonai our God, in peace; and raise us up again, our Ruler, in life. Spread over us Your Sukkah of peace, direct us with Your good counsel, and save us for Your own Name’s sake.”

I see Yehuda Amichai as a prayer-poet who wrote poems on these themes in a modern context. Because this poem feels so relevant at this moment, because he is speaking a prayer that so many of us hare holding in our hearts right now as the horrors of war continue to unfold in Israel and around the world,I would like to offer Amichai’s poem, the prayer that is “Wildpeace” translated by Chana Bloch.

WILDPEACE

Not the peace of a cease-fire,

not even the vision of the wolf and the lamb,

but rather

as in the heart when the excitement is over

and you can talk only about a great weariness.

I know that I know how to kill,

that makes me an adult.

And my son plays with a toy gun that knows

how to open and close its eyes and say Mama.

A peace

without the big noise of beating swords into ploughshares,

without words, without

the thud of the heavy rubber stamp: let it be

light, floating, like lazy white foam.

A little rest for the wounds—

who speaks of healing?

(And the howl of the orphans is passed from one generation

to the next, as in a relay race:

the baton never falls.)

Let it come

like wildflowers,

suddenly, because the field

must have it: wildpeace.

[1] Content originally published at On1Foot, a project hosted by American Jewish World Service.

“Miracle” by Elana Bell

I think it’s fair to say that many of us are hoping for a miracle of some kind. And so, as Rosh Hashanah begins, I want to share Elana Bell’s poem Miracle. It is from her book Mother Country, which explores the journey to motherhood.

The poem is about something so many of us have found difficult over the past year—just keeping on. And it is also about what to call what we are experiencing, what to name it.

Like all of Bell’s poems, “Miracle” has a lot going on between the beginning and the end.

Elana Bell’s latest collection, published by BOA Editions in 2020.

MIRACLE

What else to call the way the bare branches

I’d bought at the neighborhood bodega

came back to life that winter.

I’d carried them home— dry, wrapped

in paper—stuck them in the square vase,

and, as an afterthought, filled it with water.

I don’t know when I noticed the pale

pink shoots sprouting from the submerged

ends: wild, reaching roots, like ginseng, or the hair

on an old woman’s chin. Then tiny green

leaves began to appear at the tips,

curling over themselves with the sheer effort

of growing.

I’d thought they were dead.

And now I recall being in the grip

of a darkness I did not have a name for

and didn’t think I’d survive. I could try

to describe it for you now: the nights

I woke with my pulse pounding through,

the heaviness of each breath,

how the effort of being inside my body

felt like burning—

But what I really want to tell you is this:

how, in the parch of that long drought,

the people I loved kept bringing me water.

Water.

Though I turned my back, and did not answer

to my name, though I flung the cup away.

Let me say it plain: I wanted to die.

But something in me, some tiny bulb

still alive under all that rotted wood,

kept drinking, kept right on drinking.

*

I love that ending—”something in me, some tiny bulb/ still alive under all that rotted wood” that “kept drinking, kept right on drinking.”

It’s the kind of poem to return to, just as we return to prayer, in whatever form it takes for us, and to the cycle of life.

You can also hear Elana reading this poem aloud in a poetry video on her website. "Miracle" poetry video

Shana tova! Wishing all of us health, hope, peace, life, and deep meaning in the year ahead.

********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I have edited this post to include this fascinating bit of information: This version of Reb Nachman’s prayer was translated by Rabbi Shamai Kanter, alav hashalom, father of newsletter reader Rabbi Elana Kanter.

So much beauty here. Thank you.