Poetry of Survival & Light

Reading the Uruguayan poet Laura Cesarco Eglin--and singing Ladino in candlelight

When the universe feels incomprehensible, I lose myself in a bilingual edition of poetry. It is my small effort to understand the many layers of the world. If I know the original language slightly, I can follow along, as if in candlelight, reassuring myself that I can understand things, somehow. Even if I don’t know the language at all, I can still make out translation choices like stanza breaks, line breaks, and overall poem length.

I also like to listen to songs in languages I do not speak. In a song, I can figure things out with the help of music. That realization is a source of light—every time.

I hope this newsletter will bring you light.

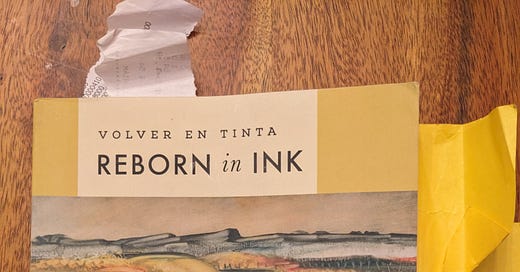

Recently, I have been rereading the Uruguayan poet Laura Cesarco Eglin’s collection Reborn in Ink, co-translated by Jesse Lee Kercheval and Catherine Jagoe—and appreciating it all the more. I have also been listening to the gorgeous and light-filled Ladino song “Ocho Kandelikas,” for Chanukah.

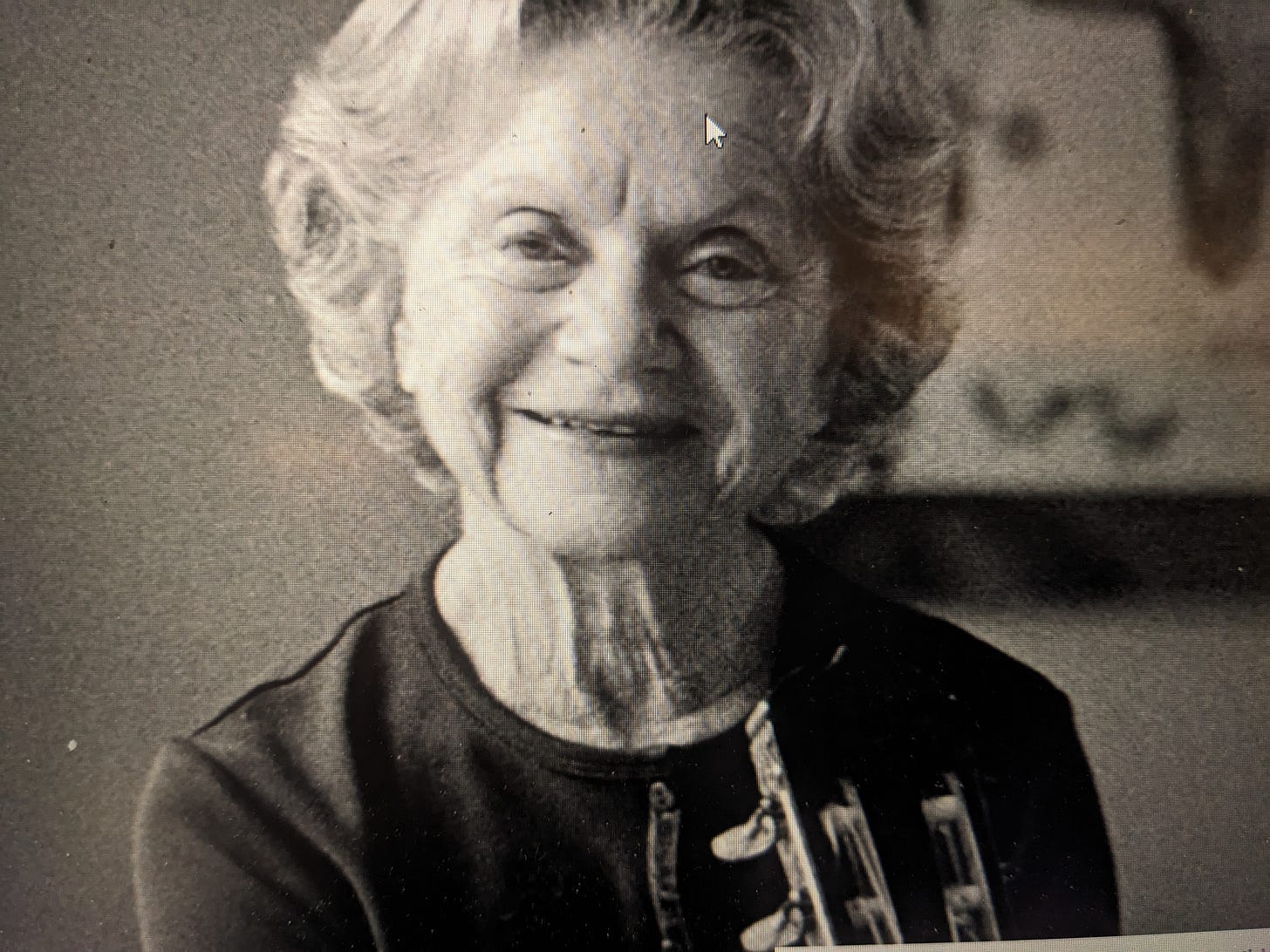

The legendary Flory Jagoda, who wrote the words and music in 1983, sang Ladino songs that her family had kept alive since the expulsion from Spain in 1492. There is history in everything Jagoda sang—and history influences Cesarco Eglin’s work, too.

And so this is the first of a two-part newsletter for this Chanukah like no other, when the past and present seem to be coming together. Part I is , this a reflection on Cesarco Eglin and Jagoda, and Part II is a Q & A with Cesarco Eglin.

Laura Cesarco Eglin

Laura Cesarco Eglin grew up in Uruguay, went to college in Israel, and earned a bilingual MFA at The University of Texas. She is an award-winning translator and the editor-in-chief of Veliz Books. I came across her work because of her translator, Jesse Lee Kercheval—also a poet and editor, and now, a visual artist with prizewinning essays that combine text and image in thrilling ways. I will read anything Jesse Lee translates.

A Brief & Spectacular Take on Grief

In Reborn in Ink, many of the poems are about grief, but just as many are about survival. I felt this combination fit well with this Chanukah like no other Chanukah in my memory, when so many of us are noticing old and new sources of darkness.

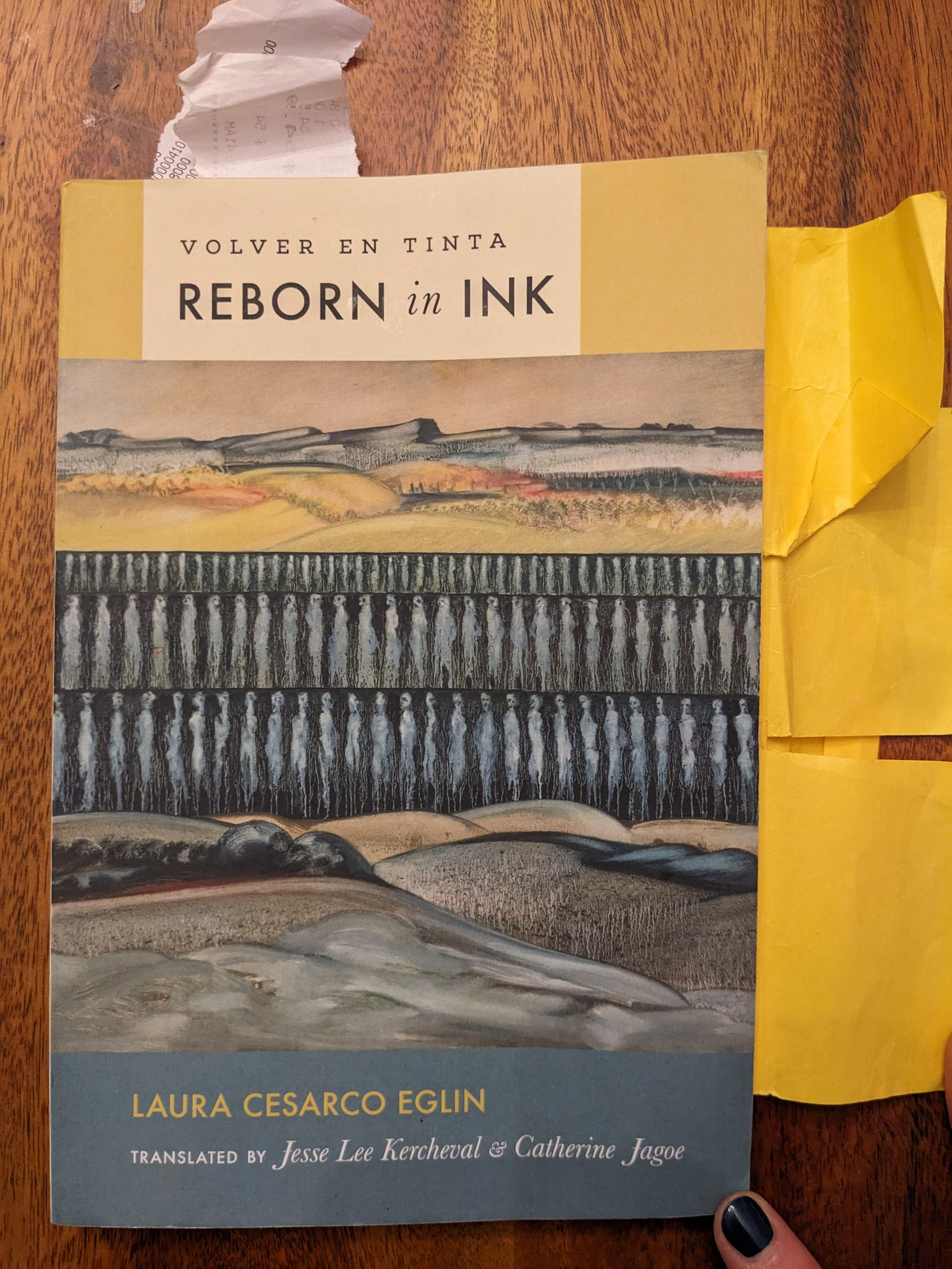

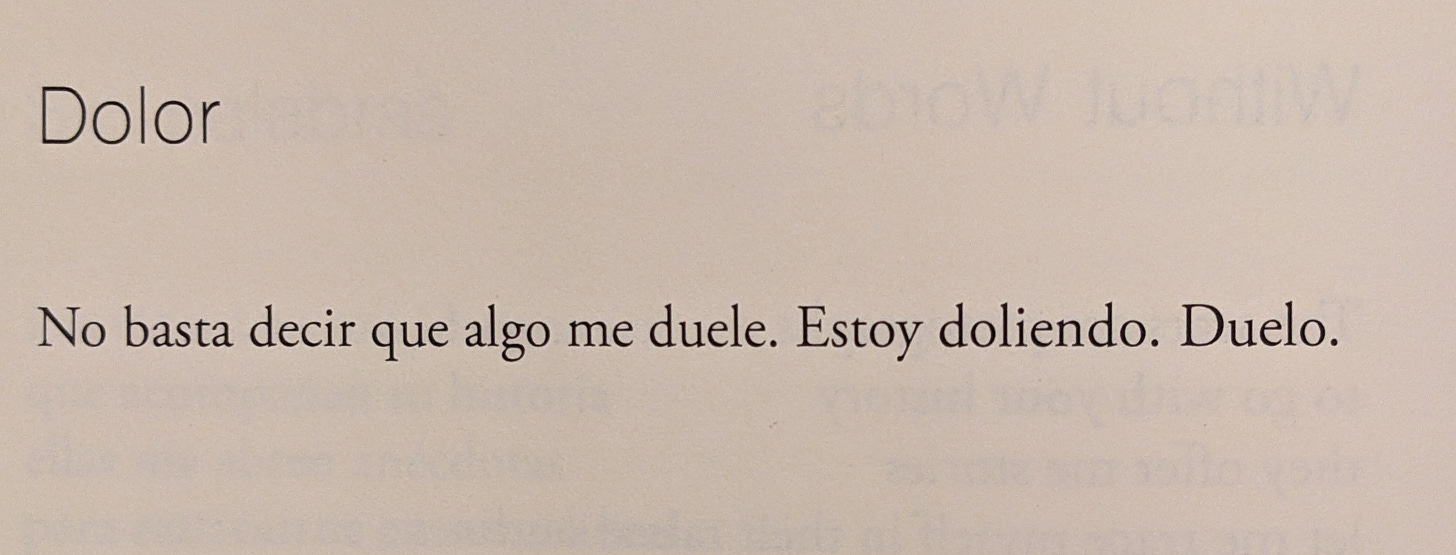

Something immediately intriguing is the length and shape of the poems in this collection, titled Volver En Tinta in Spanish. Several of the poems are just one or two lines each, as slender as a tube of lipstick—and lipstick, interestingly enough, makes an important appearance later in the collection. Here is the one-line poem “Dolor” or “Grief,” presented here both in the original Spanish and in Kercheval and Jagoe’s English translation:

“The translation challenges in this book are epitomized in the one-line poem “Grief,” Catherine Jagoe writes in her lovely and informative translator’s introduction. “In Spanish, the word dolor can mean both pain and grief.”

That line really moved me, because right now, so many of us are feeling something that can only be described as both pain and grief. It’s hard to name all the layers of this feeling, and so it’s moving to come across a word that can contain it all. Dolor—and what Cesarco Eglin does with it—is exactly why I love to read poems in many languages.

“The poem’s short statements—all variations of the same verb—play on the multiple meanings of doler (to hurt) in Spanish,” Jagoe writes. “In English, while pain and grief are clearly related, they are not contained in one word, so the act of translation forces us to choose between them, and the secondary or related echoes of meaning within the original words are not matched by corresponding associations in English.”

Why a Verb Matters So Much

Jagoe helpfully explains that the poem in Spanish makes an impersonal verb personal.

“Estoy doliendo means literally “I am hurting”—but the unusualness of that linguistic choice, making an impersonal verb personal, is lost in English. The last sentence of the poem is simply one first-person verb, even more radically personal and active yet: Duelo.”

I love the idea of a “radically personal” verb.

“One can translate this as “I hurt,” but again, we lose the iconoclasm, the fact that it is never used as an active verb, and the double meanings: duelo is also a noun, meaning two things: ‘mourning’ and ‘duel’,” Jagoe writes.

It’s fascinating to consider any word that can mean both “mourning” and “duel”.

Distance and Its Intimate Power

All of these double meanings in Cesarco Eglin’s poems raise questions. They leave room for the reader to think and feel, and that feels especially true in her ultra-short poems. Reading the two-line poem “Distances,” for instance, a reader can ask:

Does physical distance matter when it comes to human beings? Or when it comes to love?

Mourning by Fainting

I first read this collection just before it was published, in 2019—and I remember noticing the titles, like “Mourning by Fainting.” This time, I noticed the ending of that poem. The last two-and-a-half lines—so bodily, so true—also felt right for this moment, when many of us are lighting candles and thinking previously unthinkable thoughts.

Who could have imagined this year last year?

We might have fainted had someone told us. Now, so many of us are in a kind of mourning that moves around but still remains in the body: “The throbbing I feel in my eardrums was / in my heart not long ago”:

Survival Through Lipstick

It’s interesting to return to specific poems again and again, and that, I think, is part of the power of Chanukah—to return to blessings and rituals and history, and of course, the poetry and song of the holiday—again and again.

When I first read this collection, I was drawn to the poem “Makeover,” in which Cesarco Eglin memorializes Jewish women in concentration camps who dabbed a bit of lipstick before roll call to look healthier—to look alive, to be chosen for life.

Jesse Lee Kercheval, in her translator’s introduction, reminds us of the history of Uruguay, and of Cesarco Eglin’s family. I found this part especially fascinating.

“I stress the history of Uruguay as a nation of immigrants and Cesarco Eglin’s travels, countries and languages (Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Hebrew) because I think this history and her life makes a larger point. With work in translation, we can feel distant from the author, as though she were someone living long ago and far away, someone distant from ourselves, living in a fairy tale where ‘magical realism’ is a reality.”

“But people have always crossed borders,” Kercheval writes. “Cesarco Eglin’s grandparents, Holocaust survivors who left the camps first for Italy, then Uruguay, are the embodiment of this.”

The poem “Makeover”—another form of being “reborn” —makes history feel very close, almost everyday as lipstick, which appears in its memorable opening line.

A Belief in Writing

In all of Cesarco Eglin’s work, I can hear a belief in language, and in writing. It’s her form of light:

What’s beautiful about Cesarco Eglin’s work is how much she can make “reborn in ink.” I am currently immersing myself in Eglin’s three recent chapbooks. For those who want to read along, in advance, the chapbooks are: Life, One Not Attached to Conditionals, Thirty West Publishing House, 2020; Time/Tiempo: The Idea of Breath, PRESS 254, 2022; and Between Gone and Leaving--Home, dancing girl press, 2023.

And of course, please stay tuned for a Q & A with Cesarco Eglin. But first, a song.

Singing in Ladino, by Candlelight

As the days get shorter and nights get darker, I wish all of us more poetry, more understanding, more languages, and more light.

For those lighting candles, or singing, or eating cakes, here is a beautiful performance about all three essential activities in the Ladino Chanukah song “Ocho Kandelikas,” written and composed by the legendary Flory Jagoda, pictured below.

Floty Jagoda.

It was a surprise and a delight to encounter U.S. service members singing Jagoda’s song—in Ladino—on public television.

Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, also sometimes called Judezmo, is a Romance language, and it includes words and phrases from Hebrew, Turkish, Arabic, Greek, French, and Italian. It originally developed in medieval Christian Spain; after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, Ladino moved along with Jewish exiles, and then developed independently of Iberian Spanish. If you speak Spanish, learning Ladino will be easier. And for beautiful columns on Ladino, whether or not you can speak a word of Ladino, I recommend Ladino scholar Devin Naar’s Moabet column, up at Ayin Press: https://ayinpress.org/introduction-to-moabet/

For five hundred years, Ladino thrived, and was the mother tongue of generations of Sephardic Jews. It’s a beautiful language—especially in song and dance. If language can be reborn in ink, it can also be reborn in music.

Here is the song, in a performance this week:

And here is a translation of the song, from the Milken archive of Jewish music:

Beautiful Hanukka is here,

Eight candles for me.

One candle, two candles, three candles

Four candles, five candles, six candles

Seven candles, eight candles for me.

I will give many parties with happiness and pleasure.

I will eat the little cakes with almonds and honey.

Gorgeous! And with that—Hanuka alegre! Chag sameach!

********************************************************

I hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Thanks so much, Aviya. I don’t have any formal training in poetry but I’ve been finding some solace in it these days and I appreciate you bringing these poems and poets to my attention. Wishing you and all of us some light. Chanukah sameach.

Thanks for sharing the poems and the beautiful rendition of Ocho Kandelikas.