Every Seder of my life has had a moment when my father reads a Yiddish poem by Binem Heller which begins in varsheve geto, iz itst khodesh Nissan, or “in the Warsaw ghetto, it is the month of Nissan.” But other Seders at other family tables include an Italian poem, or a translation of one, by Primo Levi, written April 9, 1982.

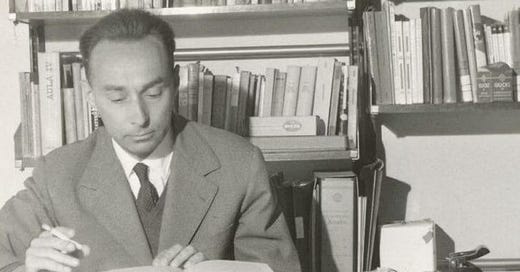

Primo Levi at his desk in 1960. (Source: Wikicommons)

Titled “Passover,” this Levi poem appears in English translation in the Schocken Haggadah (1996), edited by Nahum Glatzer, and it feels especially resonant this year, when there is so much pain and turmoil in the world, and it is impossible not to think of all of it amid the joy and reflection of Passover.

I have seen this poem re-printed with a variety of stanza breaks, including a version of just one long stanza. In any version, one line always stops me. Here, it is at the end of the third stanza.

“Evil translated into good”—feels extremely contemporary, as if it were a participant in today’s headlines. And of course, the poem begins in urgency—“tell me”—which is also, of course, deeply personal, one human to another.

PASSOVER

Tell me: how is this night different

From all other nights?

How, tell me, is this Passover

Different from all other Passovers?

Light the lamp, open the door wide

So the pilgrim can come in,

Gentile or Jew;

Under the rags perhaps the prophet is concealed.

Let him enter and sit down with us;

Let him listen, drink, sing and celebrate Passover;

Let him consume the bread of affliction,

The Paschal Lamb, sweet mortar and bitter herbs.

This is the night of differences

In which you lean your elbow on the table,

Since the forbidden becomes prescribed,

Evil is translated into good.

We will spend the night recounting

Far-off events full of wonder,

And because of all the wine

The mountains will skip like rams.

Tonight they exchange questions:

The wise, the godless, the simple-minded and the child.

And time reverses its course,

Today flowing back into yesterday.

Like a river enclosed at its mouth.

Each of us has been a slave in Egypt,

Soaked straw and clay with sweat,

And crossed the sea dry-footed.

You too, stranger.

This year in fear and shame,

Next year in virtue and justice.

About Primo Levi

Yes, Levi, a chemist, wrote poems—though he is most known for his prose. He survived 11 months in Auschwitz.

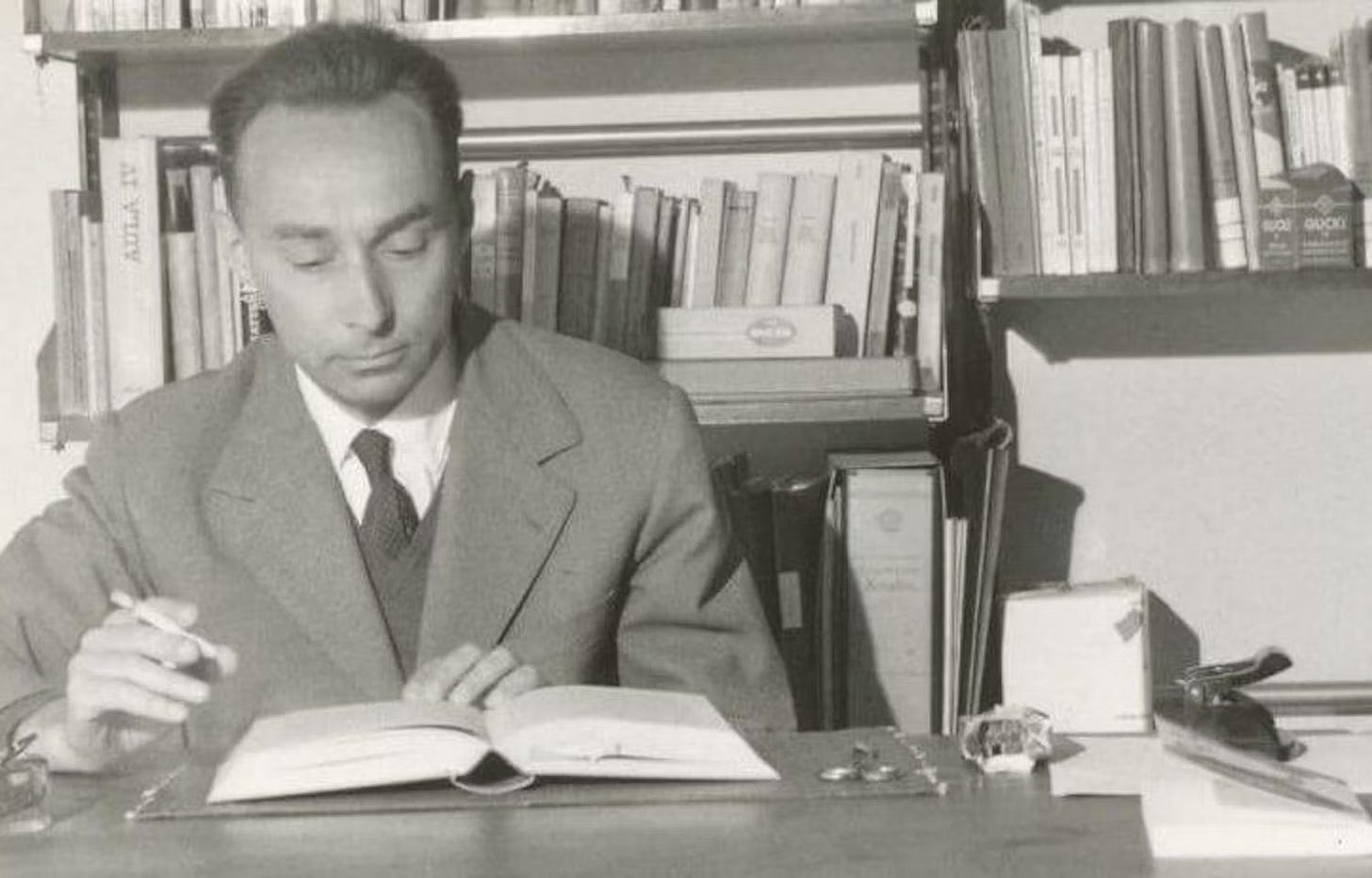

Primo Levi in 1940.

“The books and other writing of the Italian Jewish chemist, author, and Holocaust and German death camp survivor Primo Levi (1919–1987) were sadly catapulted to heightened awareness upon his apparent suicide in 1987, even though he was already recognized as a major figure in the world of 20th-century Italian literature,” Neil W. Levin writes in the liner notes at the Milken Jewish Music archive, accompanying some Primo Levi poems set to music.

“Not all of his writings are Jewishly themed or Holocaust related (or not directly so), but those that are are generally acknowledged to be sui generis in their subtlety and quiet dignity—the product of an intensely human but humble and reserved personality with extraordinary literary gifts,” the notes continue.

Primo Levi’s Poems Set to Music

The Milken archive features a poem-song cycle titled Shma, which can be translated as the imperative “Hear” or “Listen.” It of course refers to the iconic shma Yisrael, Hear O Israel, prayer. I am always interested in poets who write prose, and how poetry leads to prose. You’ll see that the fifth line of the poem “if this is a man” becomes the title of Levi’s iconic prose work. Here it is in Italian, followed by English. I hope you make time to listen to it as you read. Primo Levi's "Sh'ma" set to music

The first part of the Sh’ma or “Hear” cycle was written January 10, 1946. Here is the original Italian, followed by the English, translated by Ruth Feldman and Brian Swan.

I. Sh'ma (Hear)

January 10, 1946

Voi che vivete sicuri

Nelle vostre tiepide case,

Voi che trovate tornando a sera

Il cibo caldo a visi amici:

Considerate se questo e un uomo,

Che lavora nel fango

Che non conosce pace

Che lotta per mezzo pane

Che muore per un si o per un no.

Consierate se questa e una donna,

Senza capelli a senza nome

Senza piu forza di ricordare

Vuoti gli occhi e freddo il grembo

Come una rana d'inverno.

Meditate che questo e stato:

Vi commando queste parole.

Scolpitele nel vostro cuore

Stando in casa andando per via,

Coricandovi alzandovi:

Ripetetele ai vostri fegli.

O vi si sfaccia la casa,

La malattia vi impedisca,

I vostri nati torcano il viso da voi.

I. Sh'ma (Hear)

January 10, 1946

You who dwell securely

In your warm house,

You who find hot food and friendly faces awaiting you

When you return home in the evening:

Consider whether this is a man.

Who works in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who struggles for a crust of bread

Who dies at a "yes" or a "no."

Consider if this is a woman

Without hair and nameless

Without the strength to remember

With eyes that are empty and a

womb that is cold

Like a frog in the winter

Meditate on the fact that this has taken place:

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them on your heart

When you are at home, when you walk on your way

Lying down, rising up,

Repeat them to your children.

Or may your house disintegrate

May disease make you powerless

May your children turn their faces

away from you.

Speaking at Fordham University Next Week

I’m excited to participate in two panels at Fordham University next week as part of a celebration of the work of filmmaker Nurith Aviv. Poster and info below—if you’re nearby, would love to see you!

Shabbat shalom and chag sameach!

********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.