The past 24 hours in Tel Aviv have been about two assassinations, and degrees of fear. How quickly will history turn? No one knows. I feel fortunate that for weeks, I have been completely immersed in the world of Avraham Ibn Ezra, who lived through another very dangerous moment in Jewish history, the Second Crusade. It gives me a deeper context for all that is happening, and I hope it will do the same for you.

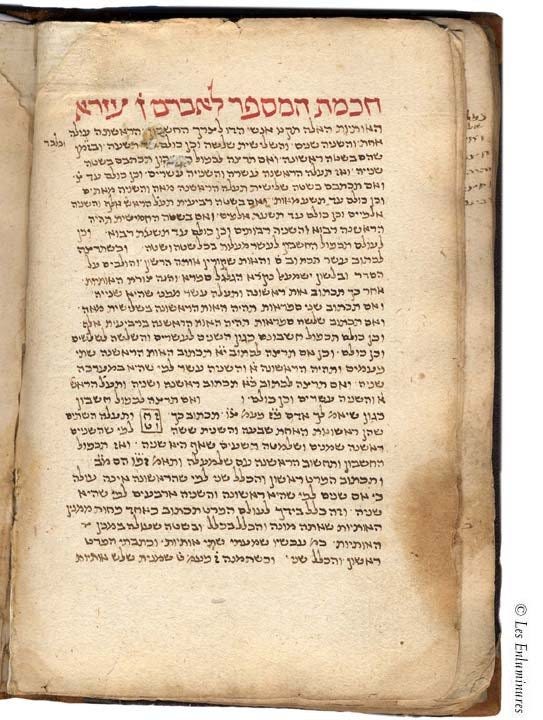

Sefer Ha-Mispar (The Book of Numbers) by Avraham Ibn Ezra. This paper manuscript is from the Balkans or Turkey, mid-to-late 15th century. For more information: https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/ibn-ezra-hebrew-60416

Introducing Ibn Ezra

In many ways Ibn Ezra needs no introduction. He lived from circa 1092-1167, and his magnificent commentary on the Torah appears on every page of the mikraot gedolot, or great readers, which is the text of the Torah with commentary. He wrote about many other subjects — including grammar, astronomy, mathematics, and the calendar.

But he was also a towering poet—and I wanted to share a poem of his that I have been thinking about, and that I had the opportunity to speak about earlier this summer at the Yetzirah Jewish Poetry Conference in Asheville, North Carolina.

I write both poetry and prose; Ibn Ezra has long been a model for me, because he is a glittering writer of both. Years ago, when I was writing The Grammar of God and trying to make the arguments of the commentators come alive for English-language readers, I was struck by Ibn Era’s beautiful prose style in his commentary, by his rebelliousness, and by his willingness to ask questions no other commentator would dare ask, such as whether the word elohim in Genesis 1:1—which can mean God or gods—indicates that perhaps there are multiple Gods.

The Mikraot Gedolot—the great readers. Here is a hardcover version of the Five Books of Moses.

Of course, the concept of one God is a core concept in Judaism. Yet Ibn Ezra actually goes there and wonders. He concludes that elohim, in the plural, does not indicate that there are literally plural gods—but rather, it is the plural form used as a path of respect.

So just as the French vous is used to indicate respect, or a plural, so here it’s a plural. What we have in Genesis 1:1 is the polite, exalted form, and so, Ibn Ezra explains, the grammar indicates that God is singular, not plural. For Ibn Ezra, grammar is often paramount; it’s the path to understanding.

Ibn Ezra's Poetry

Ibn Ezra wrote both sacred and secular poetry. One of his sacred poems is often sung on Shabbat afternoons, and it is about how God will protect him if he keeps the Sabbath. Certainly, there is something in Ibn Ezra’s life story that can make his desire for divine protection understandable. He had five children, and his only son converted to Islam.

And then there was his wandering.

In the year 1140, Ibn Ezra left his native Spain and traveled for the next 28 years. His life as a nomad was difficult and filled with poverty. He famously wrote in a poem that if he were a shroud maker, people would stop dying, and if were a candlemaker, night would never fall.

In another poem of his, which the scholar and translator Leon J. Weinberger titled “The Vagabond Life,” Ibn Ezra gives us a sense of his precarious circumstances. “Wandering has sapped my strength and confused my mind;/ My speech is halting, my tongue is chained…”

“The Flies”

One poem by Ibn Ezra, which is not among his most famous, has entered my heart. I think of it as one of his road poems, part of his nomadic oeuvre It has no title in Hebrew, but in translation, it is usually called “The Flies”.

Its opening lines showcase Ibn Ezra’s wonderful sense of humor, while also acknowledging the very real sense of oppression he feels. He’s on the road, he’s poor, he has no home. He's vulnerable to all the elements.

Here is the Hebrew, followed by two translations—one by Weinberger, from Twilight of a Golden Age: Selected Poems of Abraham Ibn Ezra, and one by Peter Cole, from The Dream of the Poem.

Even if you do not read Hebrew, I hope you can see and hear that every line rhymes, and ends with the letters that indicate a masculine plural. Take a close look at the far-left—you will see a yud followed by a mem sofit.

That first line is devastating. In Hebrew transliteration, l’mi anoos l’ezra mi’chamasi, you can hear Ibn Ezra’s desperation, his question of how to flee, how to be safe.

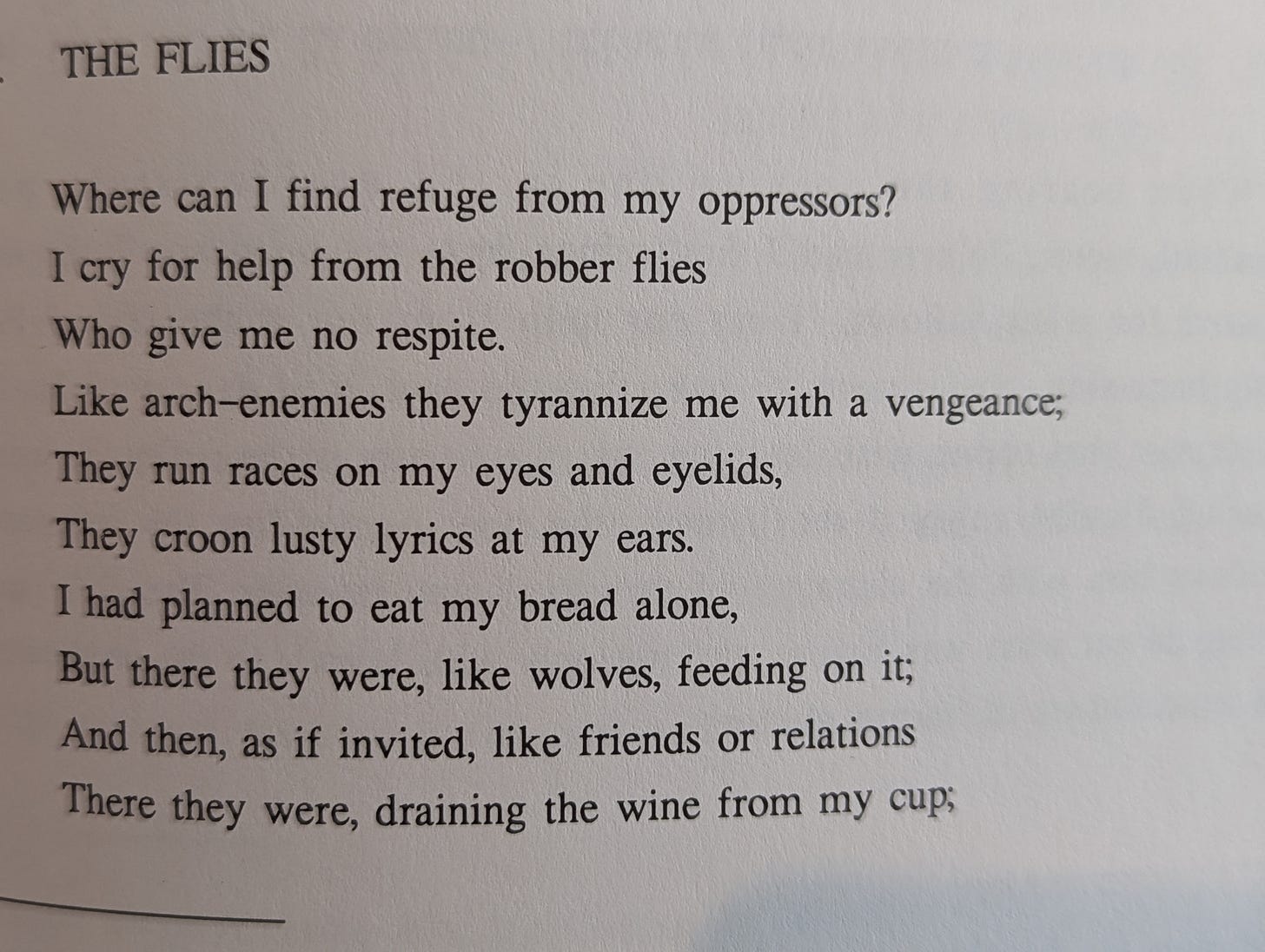

“Where can I find refuge from my oppressors?” That’s Weinberger’s translation.

Some Notes on Form

This poem is a qasida, a form of an ode. The classic form has monometer and monorhyme, and you can see and hear that here, even if you dontvreadcHebrew.

Each line is separated by a slanted line that separates it into two halves—typical of Ibn Ezra’s poetry.

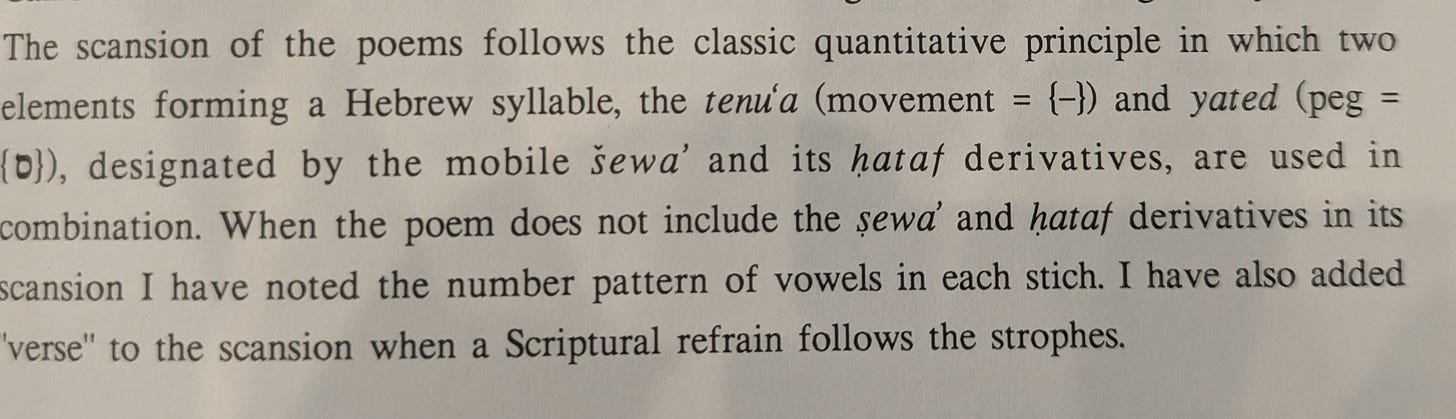

For readers who are super-interested in 12th-century poetry, I am reproducing what Weinberger has to say in his preface about the samech across the top, where the title might be, and the question of scansion. For more details, I recommend Twilight of a Golden Age: Selected Poems of Abraham Ibn Ezra (The University of Alabama Press, 1997.)

“The Flies” in English

Now let's look at the poem in English. Weinberger seems to have a religious awe for Ibn Ezra; in his acknowledgments, he thanks the One Above. What gets me about this poem is its first line, or first two lines, depending on how you are counting. It feels contemporary.

Like many of us over this past year, the piem’s opening wonders where we can find refuge from our oppressors. But then it twists—with humor, with heart—and the reader realized the oppressor isn’t a human at all. Instead, aggressive flies — “robber flies” — are the torturerz.

Ibn Ezra’s poverty and frustration with road life comes through. The flies, outside, in the elements, are ever-present, and he even looks forward to winter, to rain and snow in order to get rifd of them. And yet—the poem ends with gratitude to God.

I was intrigued by the movement from an oppressive fly to praise of God, and wanted to read more about it. I own a wonderful four-volume set on the medieval Hebrew poets of Spain and Provence by Haim (Jefim) Schirmann, which I purchased years ago at the fabulous Halper’s Books in Tel Aviv. (The book is in Hebrew. )Schirmann suggests that Ibn Ezra’s older contemporary Yosef Ibn Sahl, who died in Cordoba in 1123, was the first to write about the antics of insects. “Racing little stallions, the flies, like vultures, hasten to eat my flesh,” Ibn Sahl wrote.

So perhaps writing about flies was a trend.

Another Translation of “The Flies”

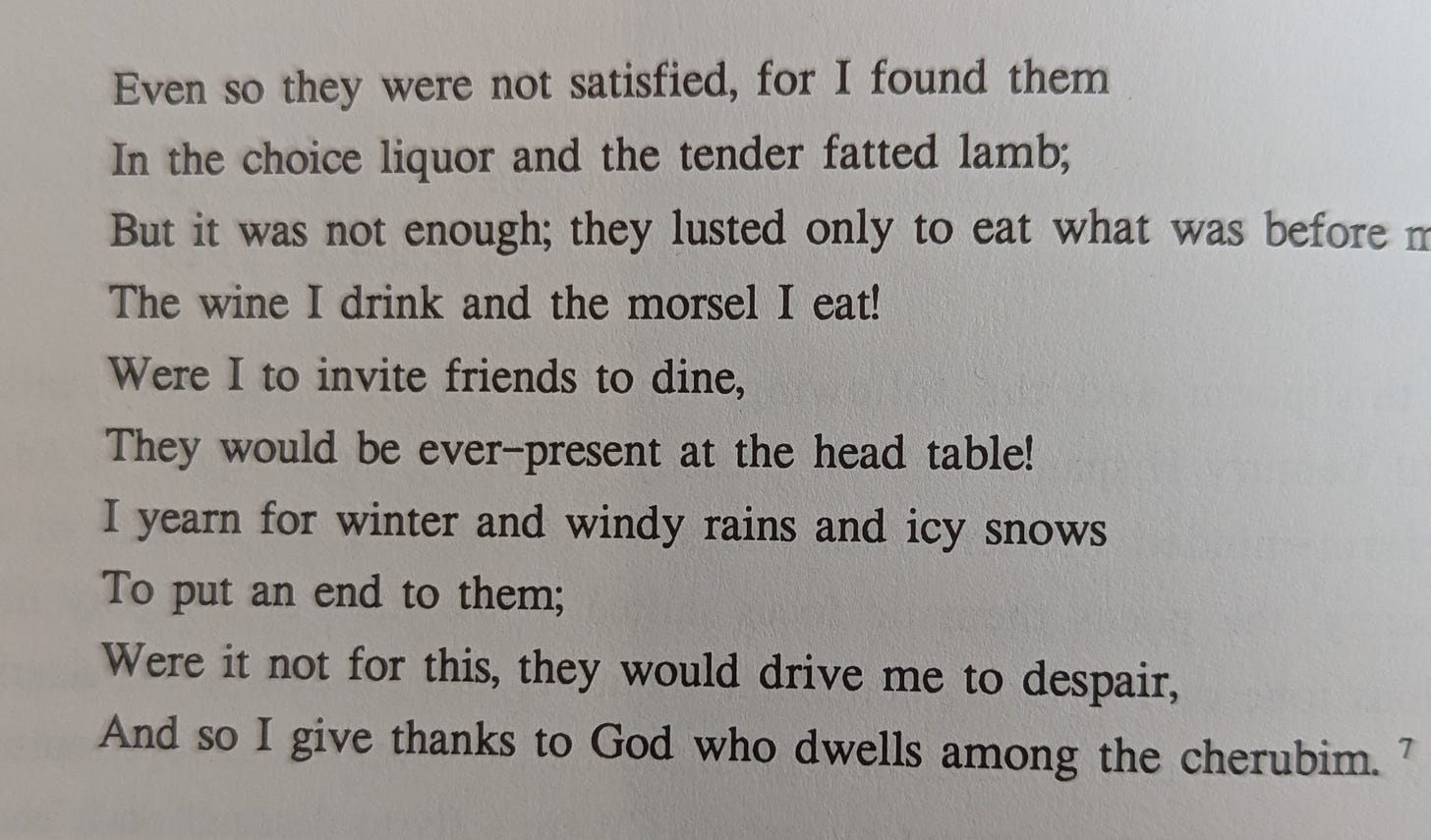

I always like to read multiple translations, so I am featuring Peter Cole’s translation here too. This is from Cole’s book The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 (Princeton University Press). As you can see, the look of the poem is different from Weinberger’s version. Cole responds to the slanted line in the Hebrew original with lineation that hints at it in English.

The Flies

Who could I turn to in my distress?

The flies have plundered my home;

they will not leave me a minute of peace,

attacking me fiercely like foes.

Across my eyelids and eyes they race;

in my ears they recite their poems;

like a pack of hungry wolves they devour

my bread when I’m eating alone,

and as though I’d asked them over like friends,

they take what they want on their own.

It seems they’re only seeking their share

when I offer them lamb and wine—

but that, it turns out, isn’t enough:

they also covet what’s mine.

If I summon guests to come and dine,

at the head of the table they swarm,

and so I long for winter lest

I starve because of them.

Its cold and rain will wipe them out—

thank God, who dwells with the cherubim.

My Ibn Ezra Poems: A Sample

For years, I have been writing poems in the voice of Avraham Ibn Ezra. Here are two, both recently featured in the new Laurel Review anthology of contemporary Jewish poetry. The first poem imagines Ibn Ezra as a nomad:

From Breaking the Glass: An Anthology of Contemporary Jewish Poetry.

The second poem here may feel relevant to all those who have felt abandoned by friends in the past year. I read that when they were young, Ibn Ezra and the great poet Rabbi Yehuda Halevi traveled to Kairowan, Tunisia, where a local claimed it was possible to visit the Tree of Knowledge. This poem imagines the effect of that on Ibn Ezra.

Upcoming Salon: Two Poet-Musicians

Last but not least, at this time of fear, gathering is what is helping many of us. I am honored to be hosting two fantastic poet-musicians, and I’ll have more details soon; I will also feature their work in upcoming posts. So if poetry or music or both soothe you, please stay tuned. Salons are for paid subscribers of this newsletter, who help make this endeavor possible. Wishing all of us safety and peace, and our leaders wisdom.

**********************************************************

Hope you found this newsletter meaningful! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Loved hearing your essay and poems at Yetzirah and revisiting them here!!

Thank you, Aviya. For bringing us close to Ibn Ezra and his torments, for bringing us close to you and to ourselves. To gathering!