Reading I.B. Singer

Why the great Yiddish master of the tale is also a master of book structure.

When was the last time you read Isaac Bashevis Singer? I ask this question in many of my creative writing classes—and nearly all my students have never heard of I.B. Singer. There was a time when Singer was everywhere. One of his short stories, “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy,” became a play, and later the Academy Award-winning film classic, Yentl. Another short story, “The Cafeteria,” became a short film in 1984. The Cafeteria (jfi.org) His work was constantly in The Forward, and of course, he won the Nobel Prize.

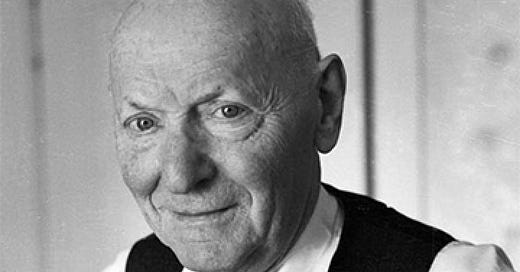

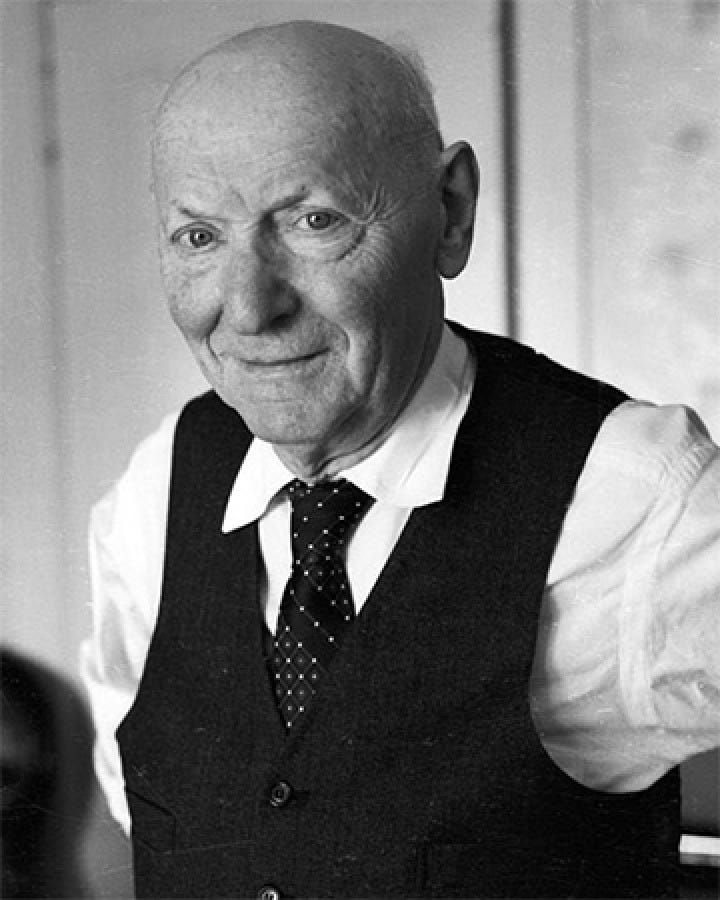

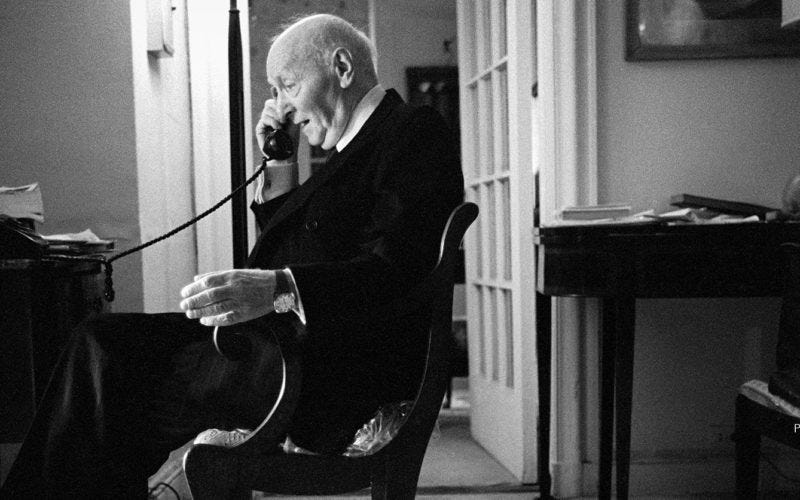

Isaac Bashevis Singer (1904-1991).

None of this seems to matter in 2024. I’m teaching a class on “Writing Place and Home”, and one of the books I am teaching is In My Father’s Court by I.B. Singer. It’s officially labeled a nonfiction book, and Singer called it “in a certain sense a literary experiment. It is an attempt to combine two styles—that of memoirs and that of belles-lettres.”

My own father read some of In My Father’s Court to me in Yiddish, when I was a child, so I have long known that there are many fabulous passages. My father’s favorite was always “Why the Geese Shrieked,” which pits rationalism against belief.

But on this go-round, I can’t help noticing that the book has a marvelous structure.

The Court as Structural Device

Singer’s idea is that the beit din, where his father was an esteemed rabbi, is a great container for a book simply because it is a great container of life. Think about it—a beit din, literally a house of justice, a Jewish court—is the site of disputes about money, love, family, land. What else could there be to say that wasn’t said there, behind closed doors?

Singer’s father’s court is in an office in their shabby apartment in Warsaw, on Krochmalna Street; many of the pieces, or chapters, detail how the Singers basically survived day-to-day, or week-to-week. Yet the court means people in all kinds of circumstances go in and out, and their presence allows a young Singer to eavesdrop and watch, getting an ideal writer’s education. And if you, like my students, want to know how to pronounce Krochmalna correctly, the fantastic, award-winning translator of Polish literature, Sean Bye, has generously provided this recording of the street name: https://recorder.google.com/cbf402ec-b66a-401b-9248-a21a015ce1d3

I love hearing that street name.

Singer obviously delights in his street. You can feel Singer’s insatiable curiosity about and delight in all kinds of human circumstances, from the very first piece—which begins with a comment on all people and the entire world, not just those on Krochmalna Street.

Addressing Everyone in the World

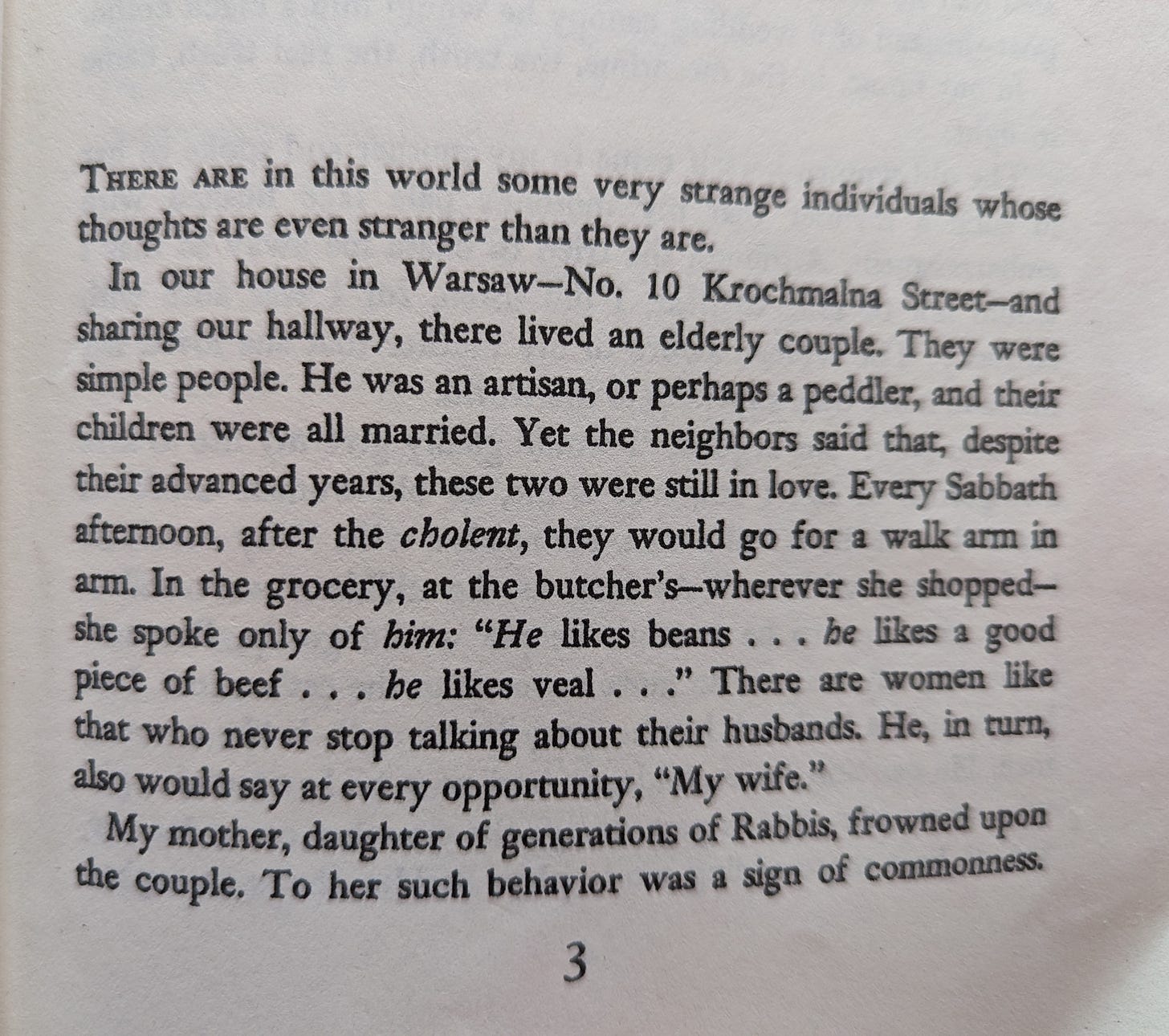

“There are in this world some very strange individuals whose thoughts are even stranger than they are.” That’s the marvelous and welcoming opening line of “The Sacrifice,” the first piece — or chapter — in In My Father’s Court.

The translators of this book are Channah Kleiner-Goldstein, Elaine Gottlieb, and Joseph Singer—I.B. Singer’s nephew. (Yes, the family aspect of this book extends to its English translation.)

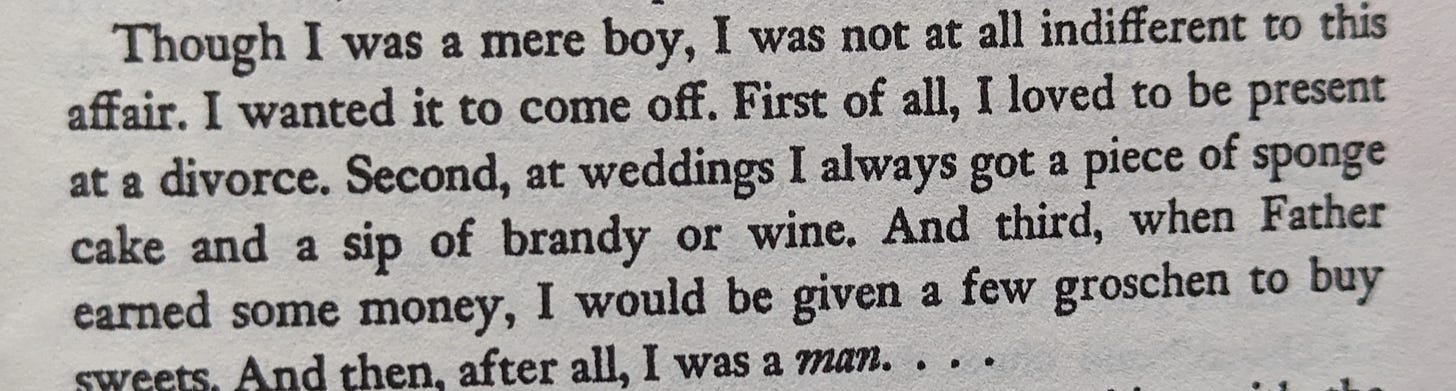

The piece goes on to describe an old woman who wants to divorce her husband, because she thinks it will be better for him. She can make do without a husband; but let him have a young wife. What’s fascinating is that it is her idea, not his, and furthermore, that Singer’s father allows it because both have agreed. But what is beyond fascinating, for anyone interested in writing, or how Singer became Singer, is how he writes his own reaction to the proceedings. He openly tells the reader that he loves to watch a divorce.

“The Will” and “The Washerwoman”

Another piece that stuck with me is “The Will,” about a prosperous man who keeps revising his own will, until Singer’s mother has to sew his version into a brochure, with string. Singer describes the man’s delight at imagining the various preparations for his death. Surely, we all know someone like this, obsessed with the details of a funeral.

And there is something in the man’s obsession with revision that is about a desire to revise life and control death—which Singer had to have felt was part of the writer’s fruitless dream.

Then there is “The Washerwoman,” an extended portrait of someone who is not Jewish—the old woman who came to take the Singers’ laundry, on her back, and then return it weeks later. “She also lived on Krochmalna Street, but at the other end, near Wola. It must have been a walk of an hour and a half,” Singer relates.

This might be a good spot to point out that in addition to the court, the structure holding this book together is the street—Krochmalna Street. And of course, to a contemporary reader, it can be shocking to realize that clean clothes took two weeks just a few decades ago. Singer’s story grants the woman deep, irrevocable dignity; she will not die until all her wash is cleaned and returned. It is a story about work, honor, and keeping a promise. It is about what Singer’s best pieces are always about—life and death.

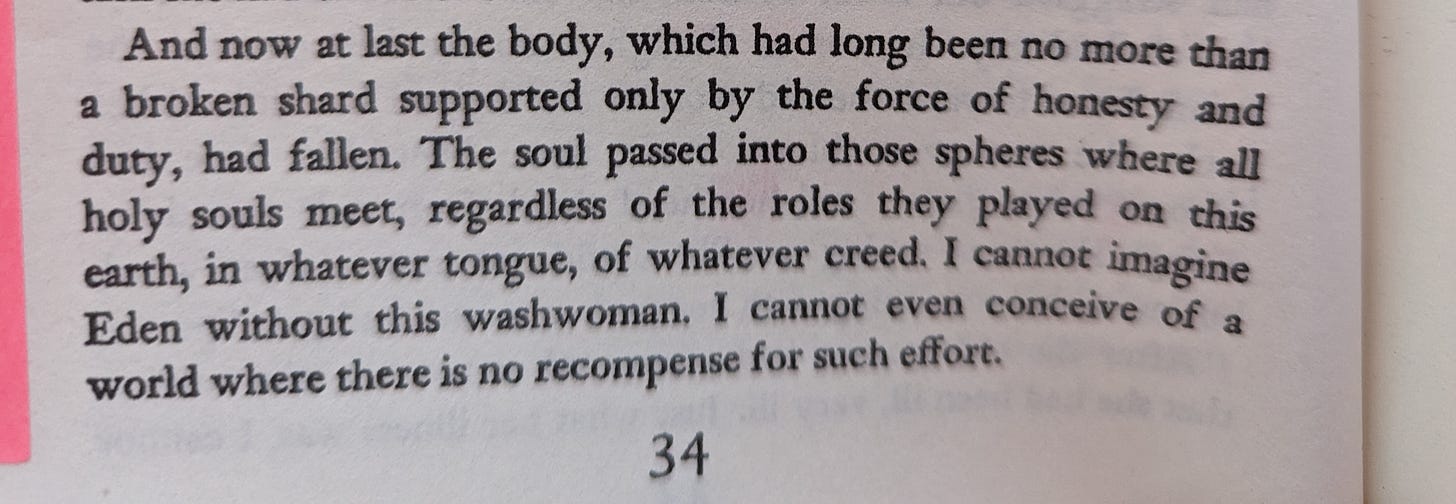

This piece has been the one that moved my students the most, especially the last paragraph.

The last paragraph of Singer’s iconic “The Washerwoman,” in In My Father’s Court.

Some Thoughts on Why Singer Is Not Read

Let’s be honest. Great Jewish literature is often not on college syllabi, especially in creative writing and literature courses. The only place Jewish writers can be featured, or so it seems, is in the segregated space of “Jewish Literature” or perhaps in “Jewish Studies”—which is not taught everywhere, including the institution where I teach.

Then there is the anthology problem.

When I was in my first year of an MFA program at The University of Iowa, I was given a list of books I could teach from and was told to pick one anthology. I leafed through each anthology and realized each did not have even one story by a Jewish writer. No Singer, no Malamud, both masters of the short story.

Not even Roth’s famous—or infamous— “Conversion of the Jews” or that oft-anthologized Cynthia Ozick piece, “The Shawl.”

I.B. Singer on the phone, shortly before he accepted the Nobel Prize in 1978.

I refused to teach from the approved anthologies and insisted on selecting my own books. I was fortunate that the wonderful coordinator—shocked once I pointed out the lack of Jewish writers—let me pick the books for my classes.

What I have learned from my years in academia is that it’s entirely possible to graduate from a top university without ever hearing “Maimonides” mentioned, let alone “Moses,” “Isaiah,” or certainly the names of great Torah commentators like Rashi, so it’s no surprise that a writer like Isaac Bashevis Singer is also not part of the curriculum.

In poetry graduate school, where my classmates were all passionate about poetry, no one had heard of the poets I listed on my personal anthology—Rachel, Chaim Nachman Bialik, and Saul Tchernichovsky, all giants, probably because they all wrote in Hebrew.

That experience of the utter absence of Hebrew literature was one of the forces that drove me to become interested in literary translation.

Hebrew’s position is shakier now. I have been present at attacks on Hebrew as a language, and on those who speak it, write it, and translate it. It happens covertly and overtly. This week, many writers I know are talking about how the literary journal Guernica retracted an essay by Joanna Chen which grapples with the terrifying reality of October 7th and its aftermath. I think it’s worth noting that Joanna interspersed her translations of Hebrew and Arabic poetry in her deeply personal piece, which began with her memories of her late aunt.

The New York Times has reported on the retraction—and the mass resignation of Guernica editors. The piece directly quotes Joanna, a writer and translator I know and have long admired. Guernica Magazine Retracts Essay by Israeli as Staffers Quit - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

The retraction is a silencing, the latest horrifying example in a growing trend. Here is Phil Klay’s take on the episode: The Cowardice of Guernica - The Atlantic And if you haven’t read Joanna’s essay, you can find it here: From the Edges of a Broken World – Guernica (archive.org)

Let me add that I love Joanna’s translation of the Israeli poet Yonatan Berg’s Frayed Light, available from Wesleyan University Press. This is a good week to read that book, which is also complicated, and layered, and born of direct experience—or you can request it from your local library: Frayed Light – Wesleyan University Press (weslpress.org)

Sometimes I feel this anti-Hebrew attitude has extended to Jewish writers who do not or did not write in Hebrew—like Isaac Bashevis Singer, who of course wrote in Yiddish. Writing in a diasporic Jewish language does not offer protection; the issue is which Jewish ideas, if any, or under discussion. Perhaps more deeply, it is about whether Jewish life—with all its messiness, like all lives—is a valid subject.

My copy of In My Father’s Court, in its latest paperback edition in English translation (1967). My students are enjoying the Post-It display….

It’s not just Bashevis who is never discussed in so-called “literary” circles outside of the Jewish world; it’s also other giants of Yiddish fiction, like Sholom Aleichem, I.L. Peretz and one of my personal favorites, the great Lamed Shapiro. Luckily, Shapiro’s The Cross and Other Stories is available in a wonderful English translation.

Literature by Jews that openly discusses Judaism—which Singer’s work does, in detail, is generally not taught in today’s creative writing courses. Neither are stories which address Jewish ideas on belief and doubt—like Malamud’s stories, with that magnificent monologue in his unforgettable story “Angel Levine” with no-yes-no-yes, capturing one man’s lifelong struggle with doubt. Challenging writing that directly explores the relationship between blacks and Jews in America—again, Malamud, in The Tenants and more—is also untouchable in many contemporary creative writing classrooms.

What that means is that the diversity of Jewish thought is becoming invisible.

Back to I.B. Singer’s Personal Life

Beyond all these sad literary “trends,” there are the personal factors on Singer, to get back to this newsletter’s subject. A known womanizer, his attitudes would not have been welcome in the #MeToo era. He abandoned his own child in Poland, as an impressive biography I reviewed long ago delved into, leaving his former partner and the child to fend for themselves. Here is that review, in The Wilson Quarterly. WQCovFall06.Sub.2 (wilsonquarterly.com)

But I think the bigger reason Singer, in all his magnificence as a writer, is not read is because he is not taught. And I suppose I am in the midst of a personal rebellion.

I tell myself the way to rebel against this is to read Singer and teach him when you can. Or find a way to mention him in conversation.

I admit that I am enjoying watching my students—one from rural South Carolina, one from Alabama, several from Chicago’s South Side, a few from deeply Catholic homes where no one, certainly, spoke any Yiddish—fall in love with Singer. I like seeing the sentences they highlight, and the moments that stick with them. The washerwoman’s dedication, and why she was the way she was, for instance. And I think, perhaps none of the biographical details matter. Beautiful writing is eternal.

Upcoming Events

I believe language is eternal, as well. This Sunday, March 17, I will be at The Jewish Silk Road of Queens, a special and rare walking and culinary tour to highlight immigrant communities and spotlight speakers and scholars of endangered Jewish languages. (You may have seen some recent articles in The New York Times on endangered languages in New York.) If you are in NY, do consider joining! Spots are limited, with discounts for current students. (I will not be speaking, but I will be listening & eating.) Events/Lectures | Jewish Languages Purchase tickets here.

On April 2nd, at 1 EST, I will be on a panel discussing “The Language of War: Lost in Translation?” with Ambassador Michael Oren, and the distinguished writers Iddo Geffen and Elisa Albert. It’s co-sponsored by The National Library of Israel and The Rohr Institute for Jewish Literature and will be on Zoom. To register: General Programs | National Library of Israel, USA (nliusa.org)

On April 11 and 12th, I will be in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to speak at the Festival of Faith & Writing. I would love to see you there! Schedule & details: Festival 2024 - Calvin Center for Faith & Writing

Thank you to everyone who came to the Celan Winter Salon, and for all those fabulous questions! Please stay tuned for info about exciting upcoming salons. Thank you, as always, readers near and far, for your support and belief.

And please, read a little bit of I. B. Singer, and let me know what you think.

**********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Zlateh the Goat and the other stories in that children's book were always favorites in my household, along with Gimpel the Fool...

Art Historian here -- After Oct 7, I started teaching Marc Chagall and 25 years of ignoring him.