Talking to Poets: Q & A with Laura Cesarco Eglin

Part II in a special two-part newsletter post

I often want to ask poets questions. While reading Laura Cesarco Eglin’s poems, I wanted to know about history and about languages. I could feel the tremendous amount of personal history in Cesarco Eglin’s poems—from the passing of a father to the Holocaust experience of what I imagined were grandparents.

I could also sense the influence of many languages. When I wrote to Cesarco Eglin, she answered that “listening to different languages, accents, and interacting with people from various cultures and backgrounds has always been a part of my life. I think that my obsession with language stems from this. The different languages I speak and translate from--English, Galician, Hebrew, Portuguese, Portuñol, Spanish--coexist and coinhabit in me when writing, when reading, when translating, when editing, when teaching, when thinking.”

I love that phrase—“coexist and coinhabit”—and have been thinking about it in relation to all that is happening now in the world.

Laura Cesarco Eglin, December 2023.

Lau Cesarco Eglin is an award-winning translator and the editor-in-chief of Veliz Books. She grew up in Uruguay, went to college in Israel, and earned a bilingual MFA at The University of Texas. She is the author of three full-length poetry collections in Spanish and three chapbooks in English.

Here is my full conversation-in-correspondence with Lau. In case you missed it, Part I of this newsletter is a reflection on Cesarco Eglin’s work, including the poems discussed in this Q &A—but really, feel free to read in whatever order you like: https://aviyakushner.substack.com/p/poetry-of-survival-and-light

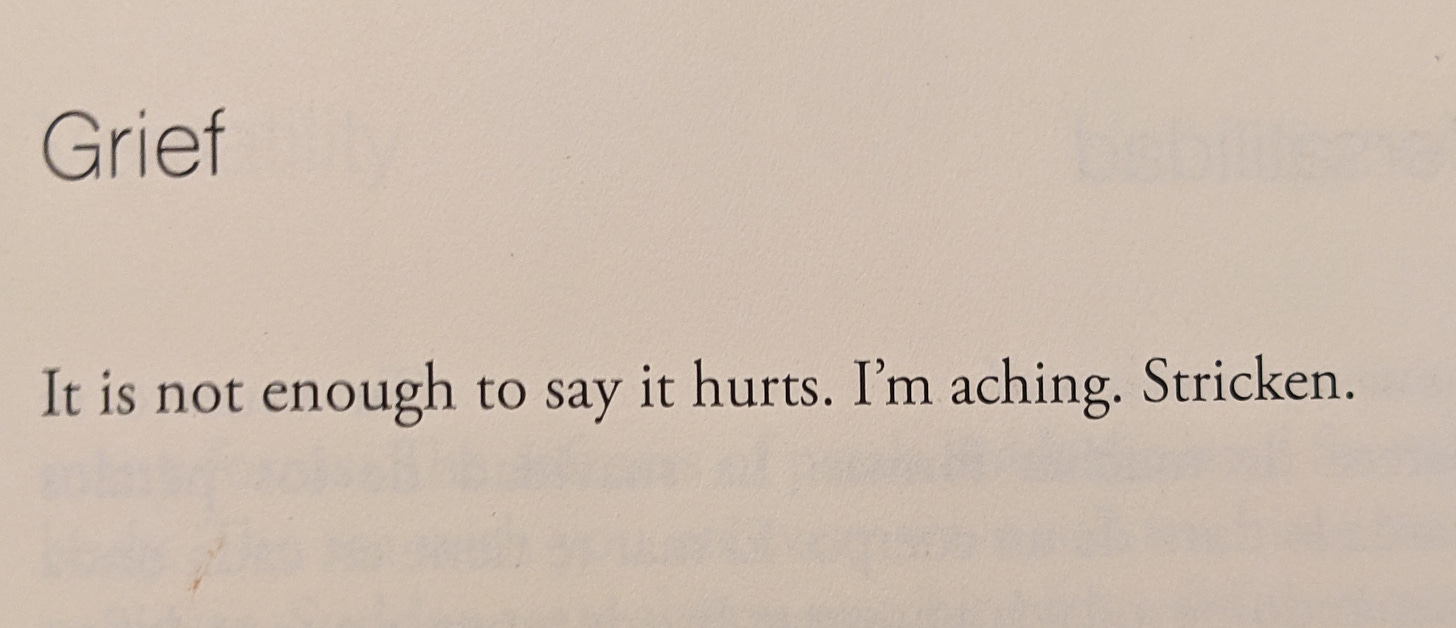

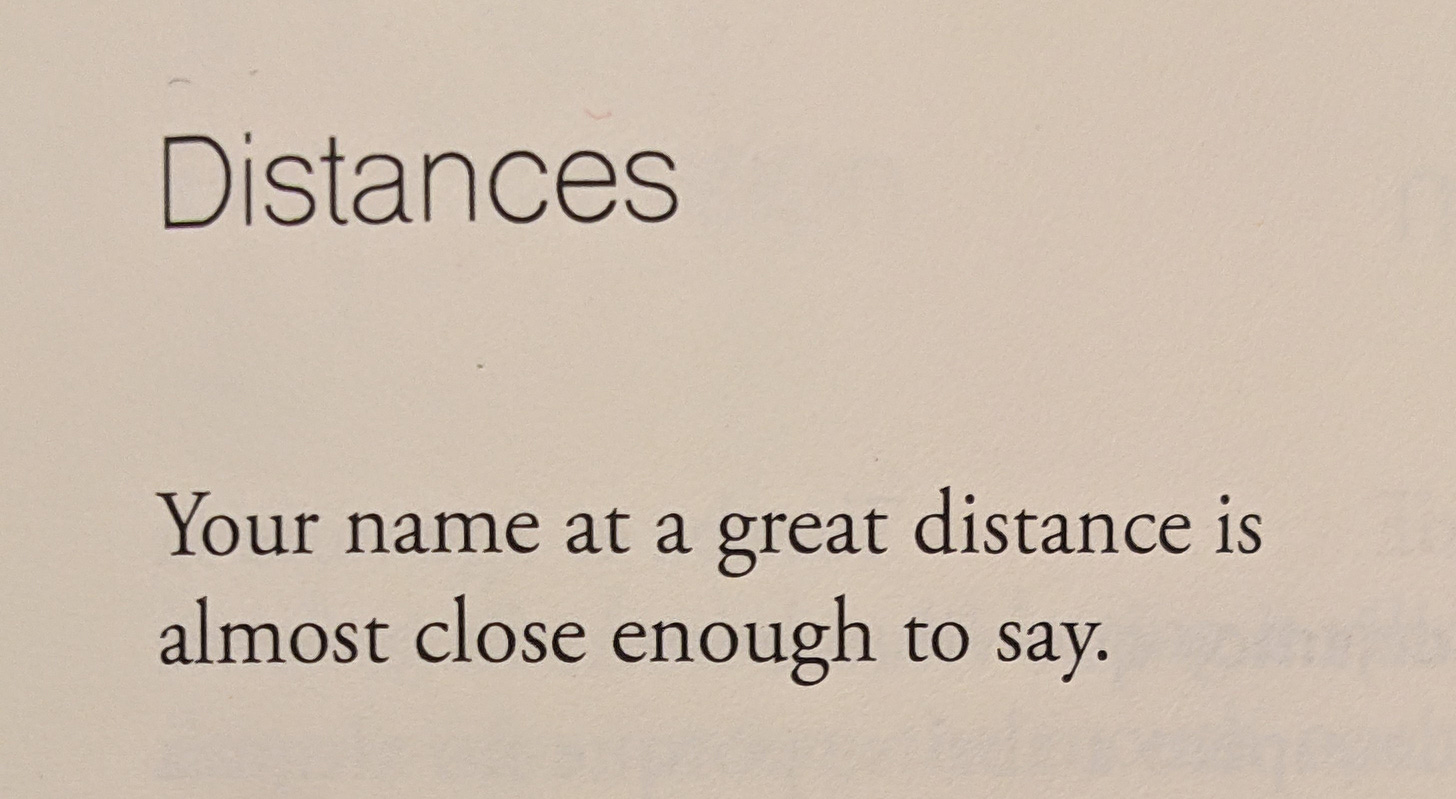

I’m intrigued by the haunting short one-line poem in Reborn in Ink, “Dolor” or “Grief,” as well as the two-line poem “Distancias” or “Distances”. What are the joys and challenges of writing such short poems?

I think that these two poems are doing things that are very much Laura Cesarco Eglin poems;), in the sense that in the poem poems experience and language are inseparable, there is an unfolding of what the poem is saying and an observation of the language used. This “double investigation,” and the tapping into different languages in the process of writing in one language permeates my poetry.

In “Dolor,” I was trying to articulate the incredible grief that comes with losing my Dad. Writing not only to understand such pain but as a way to feel. In the poem itself I’m finding ways to express this, to translate from my body to the body of the poem. I even have to resort to what is very common in English, which is to make a verb out of a noun.

“Estoy doliendo” is not something you say in Spanish, but this sorrow couldn’t be contained in the “algo me duele.” I needed language to express how active the sorrow was. The last word of the poem: “Duelo” means “mourning.” It’s a noun, but after the previous sentence, which has established how I’m using language, “duelo” also becomes a verb, conjugated in the first person singular (with the ending O). It’s a short poem with the insistence on feeling, on the all-consuming experience of loss, on different ways to express it, different ways in which I experienced having lost my Dad—and as a poet, I can’t separate these two bodies, the physical and the poem.

DOLOR

No basta decir que algo me duele. Estoy doliendo. Duelo.

In “Distancia” I’m playing with the concept of distance. Distance because I don’t live in Uruguay and because since my Dad passed he is no longer in this world where I live. A phone call “larga distancia,” is the expression used for a long-distance call, for example, but literally, it also refers to the fact that a person can be far away. The poem merges experience with language because it is through language that it is possible to bridge these distances. Someone is close if you are able to say/call their name.

DISTANCIAS

Tu nombre a larga distancia está

tan cerca como saberlo decir.

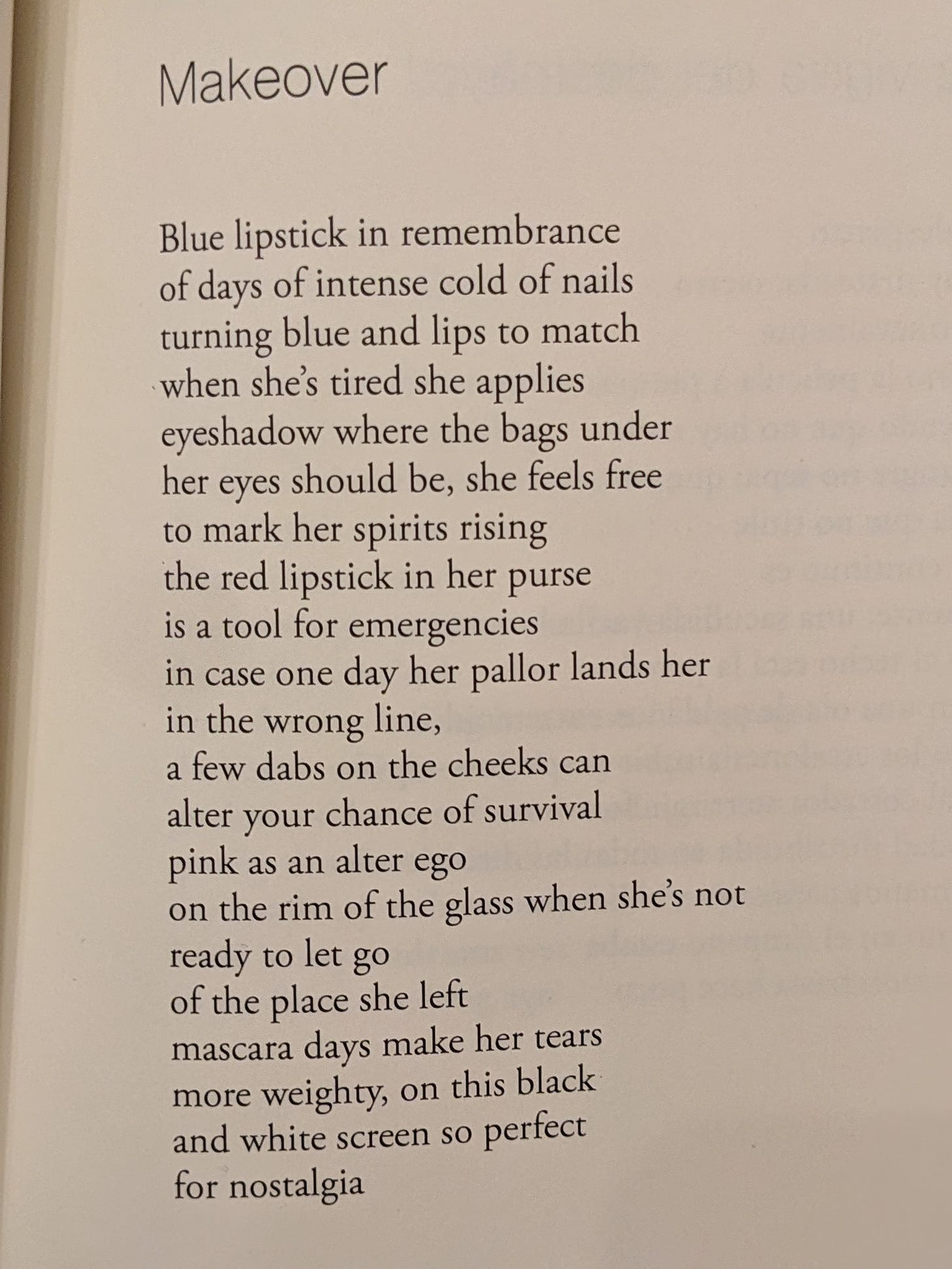

There is a lot of history in this collection, and I hope you can give me a bit more background on “Makeover” on page 55 of Reborn in Ink. I understand that it refers to the way prisoners in Nazi concentration camps tried to make themselves look a bit healthier for selection. Is there a family connection of some kind in these poems, perhaps stories told by relatives? Or is this perhaps influenced by something you may have read?

“Recobrando la cosmética” (“Makeover”) explores different instances where makeup is used and changes reality. I never wear makeup but I was observing and thinking of makeup. For instance, blue lipstick, which I associated in the poem with lips (and nails) turning blue when someone is cold. I point out the mirroring of eyeshadow with eyebags. In the middle of the poem comes the part that you are referring to,

is a tool for emergencies

in case one day her pallor lands her

in the wrong line,

a few dabs on the cheeks can

alter your chance of survival

Yes, my maternal grandparents were Holocaust survivors. I like the expression in English to name someone like me who is the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors: I am third generation Holocaust survivor. This brings my family history/experience very close, it is part of me. I can’t think of makeup without associating it with the way that some prisoners in concentration camps used scraps of food (like beets, for example) or pinched their cheeks, etc. to try to seem healthier and thus survive.

I was moved to learn in the introductions to Reborn in Ink that you went to college in Israel, and continued to the bilingual MFA program at the University of Texas at El Paso. When you were in Israel, did you study in Hebrew or in English? And I’m curious about how you think all of these languages—Spanish, Hebrew, and English---affect you as a poet, as a translator, and as an editor.

My BA and MA are from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In order to be admitted to the university you have to have level 3 of both English and Hebrew. In order to graduate from The Hebrew U. you have to have achieved level 6 of both these languages. I studied in Hebrew and in English, depending on the class.

While I was doing my bilingual MFA at UTEP, classes were indeed bilingual, and while in El Paso, I taught Spanish for Heritage Speakers, Portuguese, and different creative writing classes, some in English, some bilingual. During my PhD at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where I studied Latin American Literature, I took classes in Spanish and Portuguese, and I taught Spanish, Portuguese, and a course in Latin American Literature in translation (English).

These experiences, having lived in different cities and countries, together with being the granddaughter of immigrants, as well as my having lived in Uruguay, Israel, and different states in the U.S., means that listening to different languages, accents, and interacting with people from various cultures and backgrounds has always been a part of my life.

I think that my obsession with language stems from this.

The different languages I speak and translate from (English, Galician, Hebrew, Portuguese, Portuñol, Spanish) coexist and coinhabit in me when writing, when reading, when translating, when editing, when teaching, when thinking. There are certain ways in which these languages affect me that are easy to spot, like for example becoming a literary translator, my choice of teaching books in translation in an English creative writing class, or how in some way or other these languages come into play in my poetry.

There are other ways in which these languages and cultures affect me that are not that obvious, like how they have fostered my curiosity or how they have helped me question the status quo.

*************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Such a moving conversation. Thinking now about the ways one language can help another when it comes to trying to encompass grief in words.