It’s rare and frankly wonderful to come across a poetry collection that ends in an essay. The six-page immersion titled “El Ghetto de Mi Lengua”— or “The Ghetto of My Tongue”— provides a map to the preceding poems in Tamara Kamenszain’s collection The Ghetto, which I wrote about here.

The word “essay” isn’t really accurate; I would call this a map to the poet’s inner world, including directions to what she writes and why and how. And of course, it gives us a sense of where she is, physically, which is often Buenos Aires—seen below—but is sometimes Mexico City, or Jerusalem, or stops on a tour bus.

Puerto Nuevo, the seaport on the eastern outskirts of Buenos Aires.

The essay’s layers of meaning, in a time when layers of meaning are often flattened, was moving in all kinds of ways, and I want to highlight a few excerpts for you. But first, I should mention that it is written in combination form—prose with poems to illustrate its points, and was translated by Seth Michelson, who I will be hosting in this Sunday’s salon.

Like many of the best writers’ essays on writing, Tamara Kamenszain (1947-2021) begins with origins. The award-winning author of ten collections of poetry and four scholarly books on poetry, she explains that her first collection was titled “From This Side of the Mediterranean,” which immediately implies that there is another side.

(Or in her case, multiple sides. You can see another side of Buenos Aires below.)

Buenos Aires, aerial view at night. (Wikipedia).

Here she is, explaining her first book’s title:

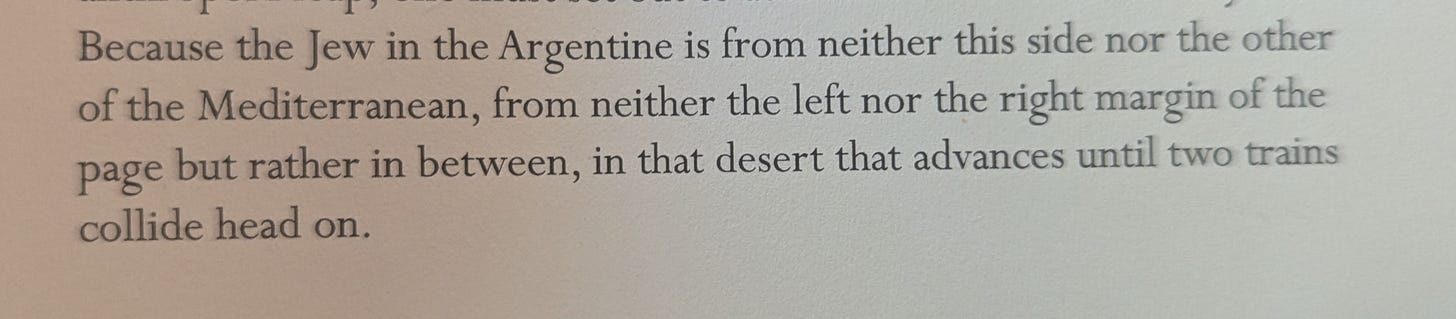

“Already, from the start, that initial title traces a chalk circle, a ghetto, a limit waiting to be transgressed. Moreover, in the very origins of my education in reading and writing there are two tongues: one—or two in one, Hebrew and Yiddish—is written right to left, and the other—Spanish—is written left to right. In the head-on collision of these two trains traveling the same rail, I also see a literary explosion.”

There is so much to think about in those sentences; the idea of writing in one direction, and then another, and the possibility of those two directions—those two hands—colliding, and perhaps, exploding against each other.

Tamara Kamenszain, poet and essayist, (1947-2021)

I was also interested in her takes on the individual languages of her inner world.

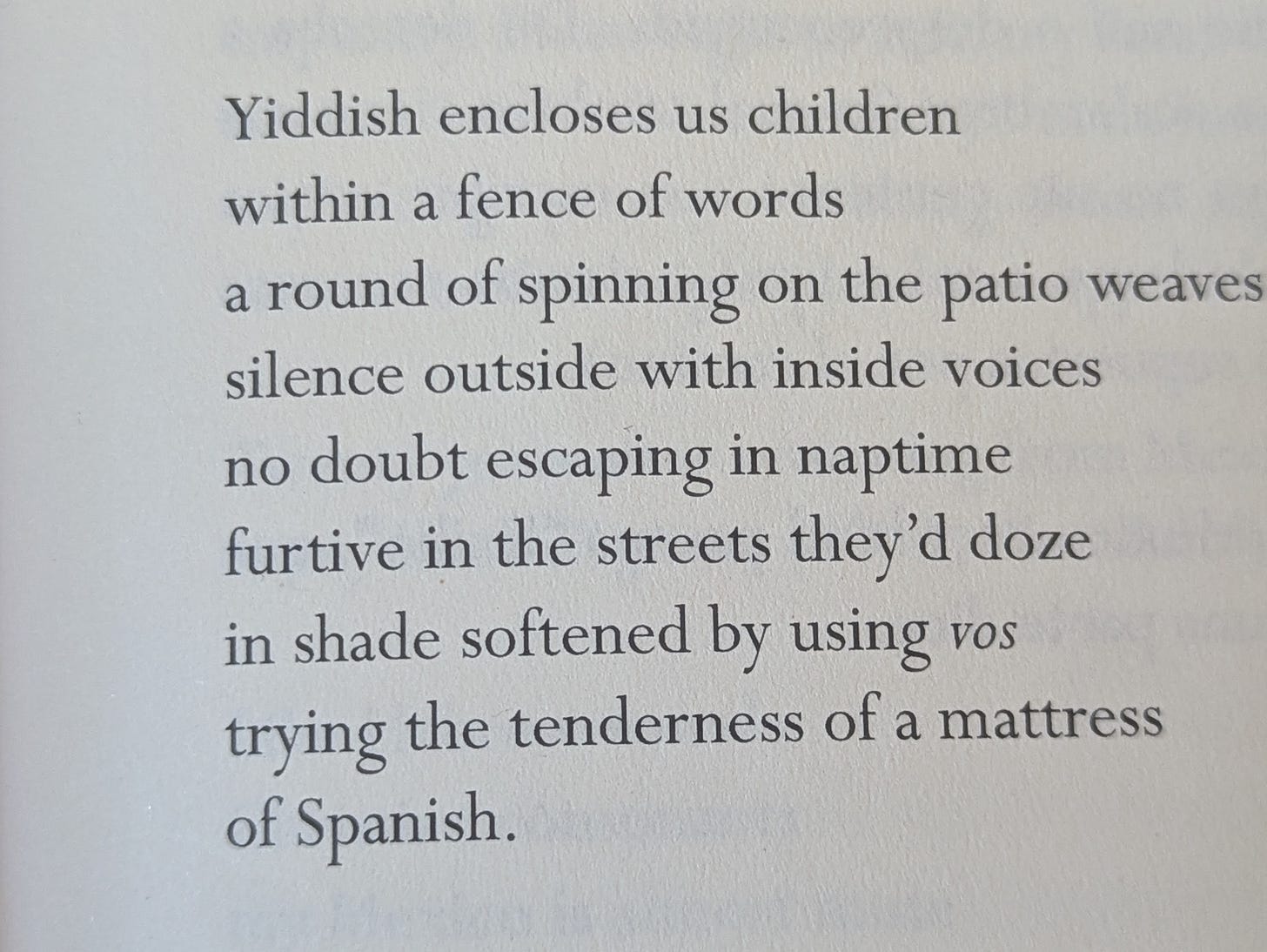

Kamenszain writes that in her 1986 collection The Big House, “Yiddish appears as a language of enclosure, with Spanish as the possibility to transgress those boundaries.” I was intrigued by the concept of some languages working to keep a writer in, and others working to let a writer get out.

I have heard writers who write in English as a second language say that they felt freer in English, less tied to parental concerns and community mores. Here is Kamenszain on how Yiddish kept her in:

The “fence of words” is intriguing to think about. And as someone who writes both poetry and prose, I was especially interested in Kamenszain’s description of how prose was much harder for her than poetry.

“Once, when I was complaining to my psychoanalyst about the effort it took for me to write essays as opposed to the relaxed sensation that accompanied my poetry writing, he remarked that surely I wrote essays from right to left and poetry vice versa.”

Tamara Kamenszain, poet and essayist.

While the psychoanalyst did not say more, Kamenszain began to think that “perhaps he’d meant that the hand of the essay delivered the weight of the Commandments, paternal law, the language of knowledge and reflection, while poetry came from the street, with its goy games at naptime on a mattress of Spanish.”

You can see why I was fascinated, and why I was reading this in the lead-up to Shavuot, with its “weight of the Commandments”… and now, perhaps, returning to “the street” after it, I am thinking about it again. (And of course, phrases like the “mattress of Spanish” are why this is a writer worth reading.)

The last bit I want to highlight is the very end of the essay.

I loved this idea of being in-between; it is something I often feel. This concept of a train about to collide head-on, of the different aspects of language and identity crashing, is also something I have been thinking about.

I’ll try and entice you to read the whole thing by not quoting all that comes before—but what I will say is that spending a few weeks with this collection has helped me understand why scholars of Jewish languages find it so interesting. If you’re feeling split, or bilingual, or multilingual, this collection of poetry, which concludes in prose, may be for you.

Salon on Sunday June 8th at Noon

I’m thrilled to host Seth Michelson, the translator of these incredible Tamara Kamenszain poems and “The Ghetto of My Tongue” essay, and poet Gail Newman, author of Blood Memory, at the next salon on Sunday, June 8th at 12 noon EST on Zoom. The event will be a reading & conversation on how this work was made.

Michelson is an award-winning poet, translator, and scholar who is a professor of poetry at Washington and Lee University. As a translator, he focuses on feminist poetry. Michelson’s recent books of original poetry include Swimming Through the Fire and Eyes Like Broken Windows.

Newman, who was featured in the newsletter here, was born in a Displaced Persons’ Camp in Lansberg, Germany; both her parents were Polish Holocaust survivors. She has worked as an arts administrator at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, co-founded Room: A Women’s Literary Journal, and edited two books of children’s poetry. She is also the author of a previous poetry collection, One World, published by Moon Tide Press.

Poet Gail Newman.

Salons are thank-yous for paid subscribers who make continuing this journey into the timeless possible, and are a chance to get to know writers, translators, and thinkers who deserve more attention. Annual, monthly, and gift subscriptions are available, and new subscribers who sign up by 11:30 EST Sunday will receive Zoom info. Paid subscribers can access the full archive of salon recordings and newsletters.

I appreciate all your wonderful comments, emails, and support, and hope to see you Sunday!

********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I’m so sad to have missed this Salon. It must have been so filled with wonder. I always leave your salons with my brain on fire, which means it is operating in its favorite environment. Off I go now to find these books.