The Poetry of Vicarious Witness

On two haunting collections by the children of Holocaust survivors

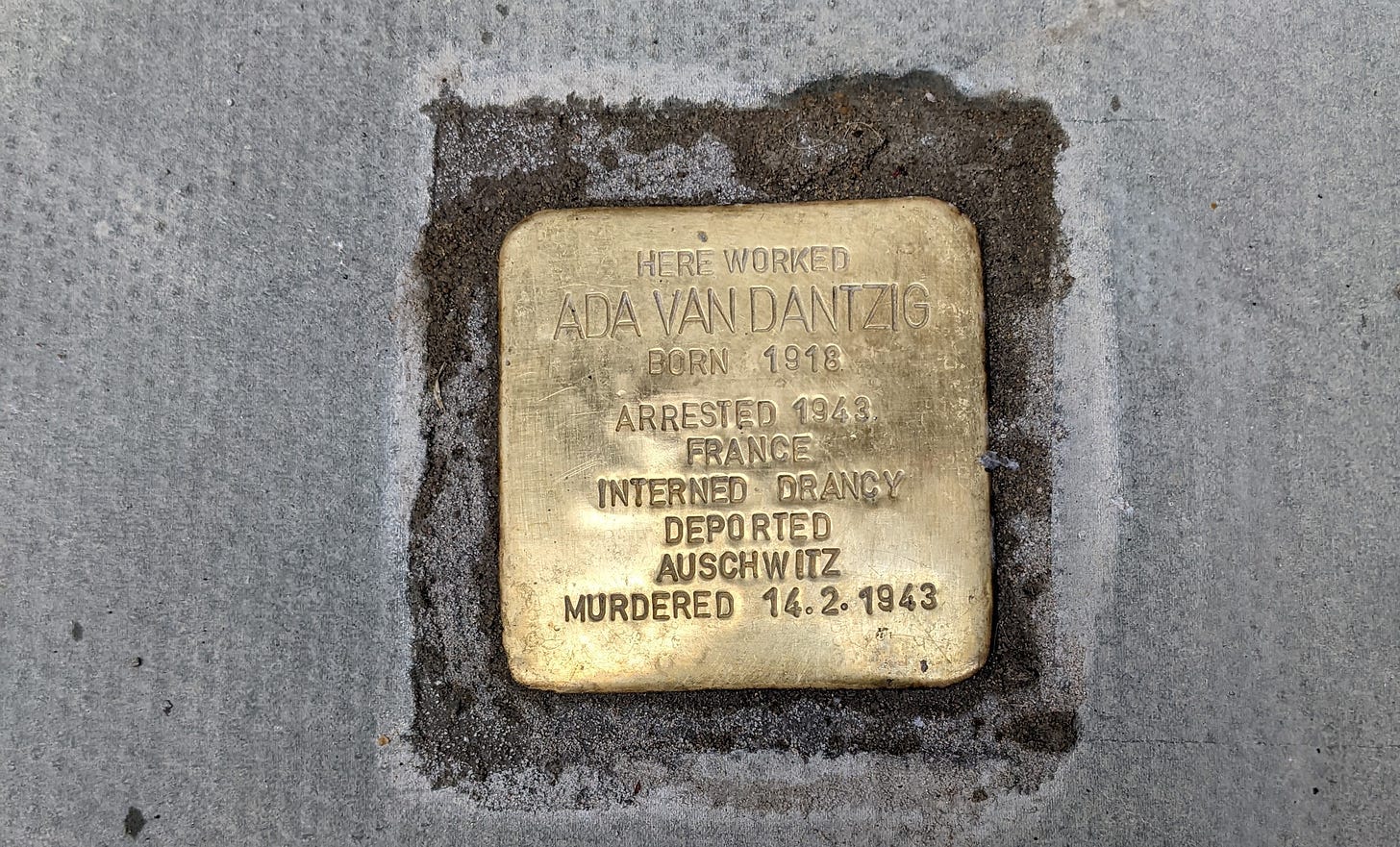

I was in London when the first Stolperstein—or “stumbling stone”—was installed in the United Kingdom. It was a small memorial in the sidewalk for Ada van Dantzig, who worked in Soho, where she studied painting conservation with the famous conservator Helmut Ruhemann—a German Jew who fled Berlin after being thrown out of his position at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum. In 1939, Ada made what turned out to be a fateful decision. She returned to her family in Rotterdam, with the hope of helping them escape the Nazis.

Ada’s escape plan failed. She was arrested along with her family, sent to Drancy, then murdered at Auschwitz; she was just 24 years old. I thought of the effort to memorialize Van Dantzig when I read two recent poetry collections by the children of Holocaust survivors—one of which reimagines an aunt who was murdered at 23.

Ada Van Dantzig, who is now memorialized in a Stolperstein in Golden Square, London.

For the uninitiated, the Stolpersteine project is the largest dispersed memorial to the Holocaust; at last count there were more than 100,000 memorial stones in two dozen countries; each a marker intended to indicate where a victim of the Holocaust last lived by choice. Once you are aware of them, it is impossible to walk through Berlin and other European cities without seeing them, in cobblestone sidewalks—lives reduced to a birth date, deportation date, and address. And then you can read—“Here lived….”

But who owns memory? Who gets to memorialize the dead? Lately, I can’t stop thinking about these questions.

Different Kinds of Memorials

In honor of the first Stolperstein in London, there were a series of events at the Wiener Holocaust Library, housed in an elegant townhouse in Bloomsbury. A psychologist spoke of the deep effect the Holocaust had on those who weren’t even there, namely the children of survivors. Her entire career was helping survivors’ children.

The Wiener Holocaust Libarary on the rainy day when I last visited.

I thought of that talk and the many nodding heads in the audience when I read recent books by Yerra Sugarman and Karen Alkalay-Gut, both born just after the Shoah ended. Both grew up in communities of survivors. Alkalay-Gut’s parents ran a Yiddish reading series and knew the great Yiddish poet Israel Emiot. Both poets have a deep connection to Yiddish, and both translate poetry from Yiddish to English.

I want to highlight two poems from each collection, and I have also asked each poet to answer three questions in a brief Q & A.

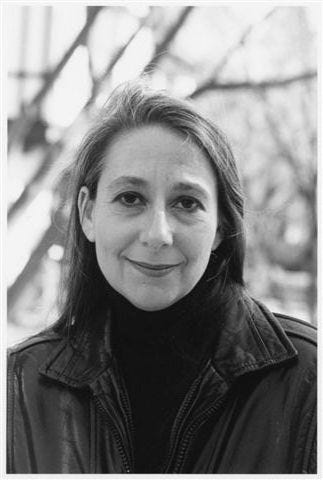

Yerra Sugarman, photographed by Bernard Gotfryd in 1999. Gotfryd survived several concentration camps, then came to the U.S. and became a photographer for Newsweek. He even photographed W.H. Auden, who convinced Gotfryd to write the story of his life.

Imagining a Murdered Aunt

Aunt Bird reimagines Yerra Sugarman’s murdered aunt, Feiga, who perished in the Kraków Ghetto at the age of twenty-three. Aunt Bird is a deep, resonant collection that came out of years of thinking about a person the poet never met—and wondering if it is entirely okay to do so on the page. A National Jewish Book Award finalist, it is the kind of book that needs to be re-read.

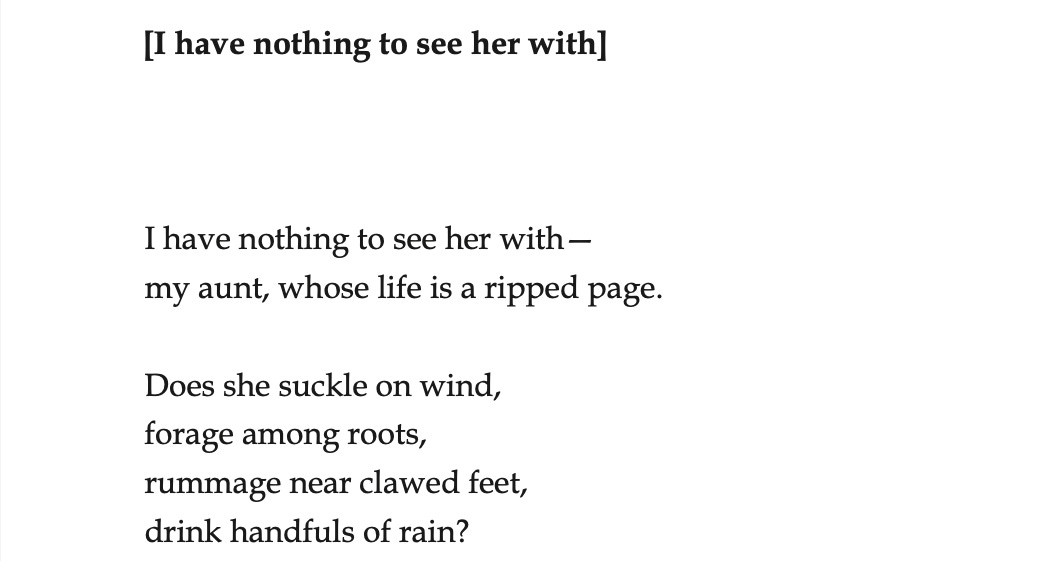

There is something mesmerizing about Sugarman’s attempt to put her aunt on the page, at times directly confronting the evil in front of her. Here is the striking first poem in Aunt Bird:

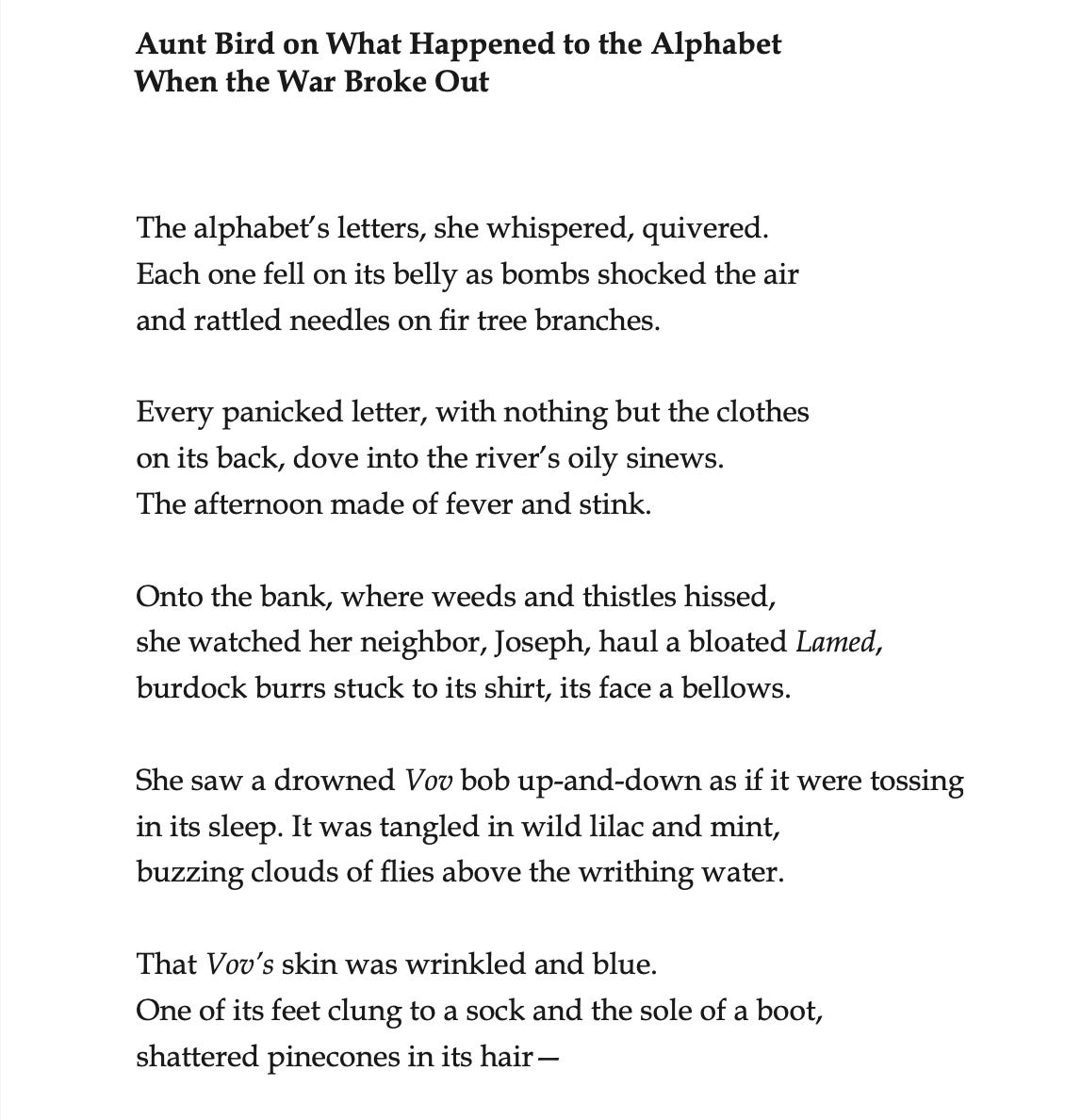

“Her life was like a thick soup in my mouth,” Sugarman writes. Then come poems where Feiga is reborn as “Aunt Bird”. Here, Sugarman invokes the Lamed-Vav, or Lamed-Vov in Yiddish, or 36. In Jewish tradition, the world continues because of just 36 righteous people.

A Quick Q & A Yerra Sugarman

Three questions and three answers.

I was intrigued by a sentence in an interview you did with Tiffany Troy for Tupelo Quarterly about visiting Kraków — “In 2008, I traveled to the city. I did so specifically because I wanted to work on some sort of poetry collection, but I didn’t know, exactly, what it would be.” At what point did you realize you were going to write about your aunt Feiga? Was there a moment that sparked this book?

I visited Kraków in 2008. It was the first time I’d ever been to the country of my parents’ birth. My mother and father, having survived the Holocaust, never returned to Poland after they left in 1946. From the plane, I felt my stomach churn with wonder at this thought as I landed.

I was particularly inspired to travel there because I had by means of a random Internet search, discovered documentation about the murder of two of my mother’s sisters: my Aunt Feiga Maler and my Aunt Chana.

Yerra Sugarman’s aunt Feiga, in the only photo of her the poet has.

My mother spoke, when she did at all, in fragments about her two sisters who’d been killed. She didn’t know their exact fates, but told me that my Aunt Feiga (her name means “little bird” in Yiddish) had been a teacher and scholarly. I felt a bond with her. I knew I had to go to see the place where my aunts had lived and perished. In 2011, I started to reimagine my Aunt Feiga’s life, and the book evolved from that point.

Writing about murdered relatives we never met is a deeply challenging project on so many levels. I can feel you grappling with the morality of it all. What concerns did you have, and what were perhaps the surprises of overcoming those concerns?

The moral principles at stake loomed over me the entire time I wrote Aunt Bird. It's something that the Israeli author and Holocaust survivor Aaron Appelfeld, discusses. Appelfeld essentially stated in Yiddish, that you cannot ethically, cannot effectively, represent the Holocaust directly; you shouldn’t dare, he cautioned.

I knew that I was “appropriating” my Aunt Feiga’s unspeakable life, and questioned the ethics of my doing so. I actually put the book aside for many years because of my worry about the morality of writing about a life whose fate was so utterly and horribly unknowable. It was a big problem to represent my aunt by means of my vicarious witness, through stories told to me about her, and testimony I found. I had to weigh the problem of silencing her completely with at least creating a prism of her life.

I hope you can talk a bit about structure and your choice of your beautiful opening poem. What notes were you hoping to strike with that first poem? How does it introduce the book, in your mind?

“[I have nothing to see her with]” sets the book in motion as an exploration of a lost and silenced life. The exploration proceeds through the book's multiple poetic modes, forms, and genres; in fact, Aunt Bird has been described as a book-length elegy.

The dead of the Holocaust are, in fact, truly my muses. I hope that isn't inappropriate for me to say, but it has always been that way, and continues to be so for me. That first poem asks a question because it is impossible to comprehend genocide, and the human capacity to inflict suffering on others. The speaker is shocked, and also bewildered, into questioning and grasping her aunt’s fate.

Contemporary Poetry in Yiddish

Karen Alkalay-Gut was born in London in 1945 and has lived in Israel since 1972, and for many years, she taught at Tel Aviv University. She is the author of more than 30 books, most in English and some in Hebrew. Alkalay-Gut’s mother tongue is Yiddish. I was amazed to learn that her most recent book, Yerushe, or “Inheritance,” was written in Yiddish—she then translated it into English. In fact, Yerushe is her first book in Yiddish. This week, the Yiddish-Hebrew edition goes into its second printing. (Yes—poetry in Yiddish sells out!)

It occurred to me that Yerusheh or Inheritance is the rare book that appears in the main languages Jews speak today: Hebrew, English, and Yiddish.

Karen Alkalay-Gut

Inheritance has a lovely and haunting dedication, “to the memory of M. Kaganovich and our entire family – the Rosenstein, Kalmanovich and Kaganovich victims and survivors, who spoke to me in Yiddish – in my life and in my dreams.” The book’s introduction is largely about Alkalay-Gut’s relationship to Yiddish; like the rest of the book, it appears in both Yiddish and English. A link to the full Hebrew-Yiddish text appears at the end of this newsletter.

“Sometimes a certain kind of love that went beyond language that could be shared only certain ways made Yiddish the language of choice. Offering a piece of birthday cake, for example, where lekach, the word for cake in Yiddish, is also the word for a lesson, and is put forward to be incorporated.”

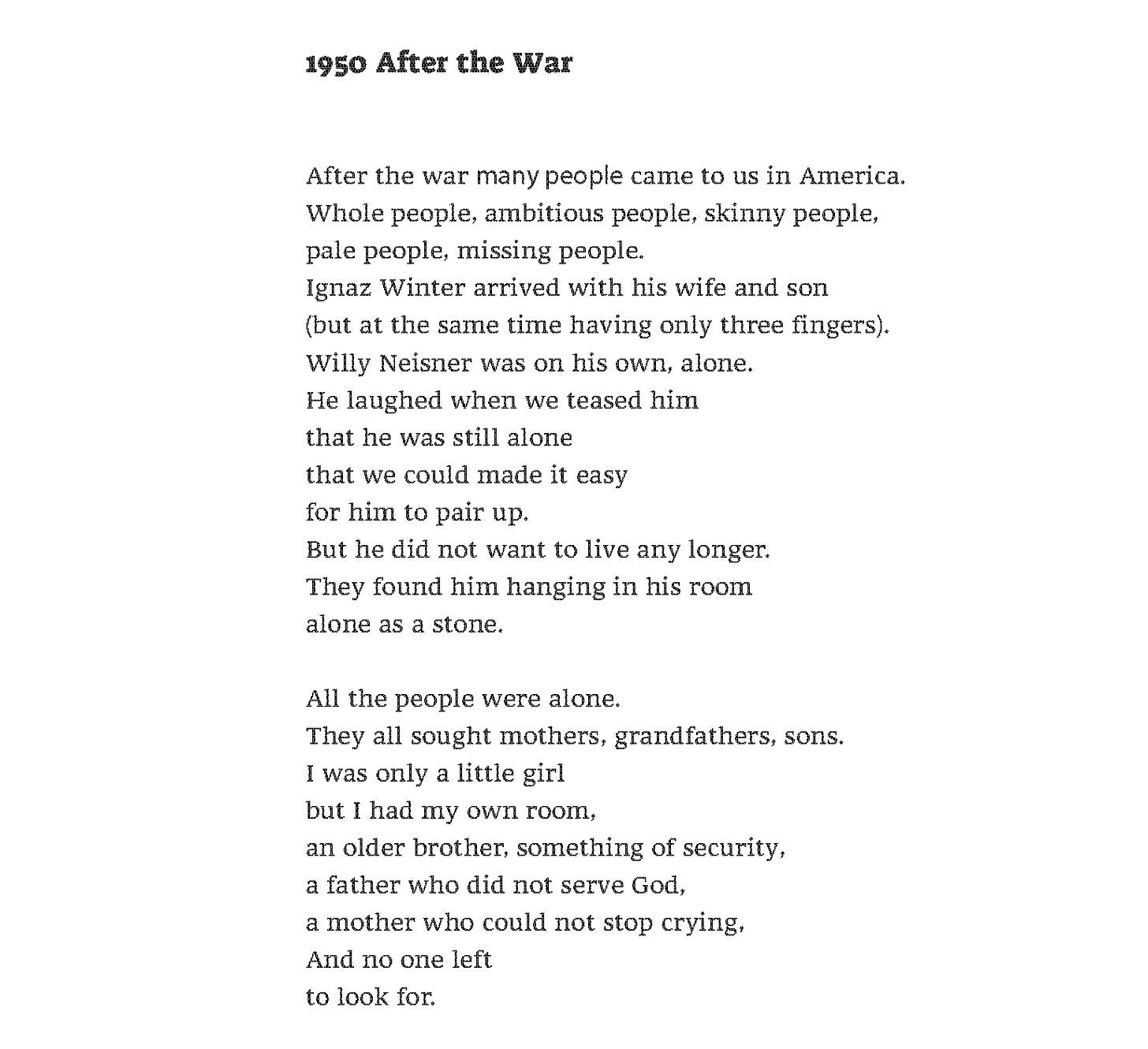

Other poems take on the Holocaust directly. I find the aloneness evoked here quite haunting (Yiddish originals at link at end of post).

Quick Q &A with Karen Alkalay-Gut

Three questions and three answers.

In your introduction to Inheritance, you write that your encounters with Yiddish writers like Chaim Grade, Avrom Sutzkever, and Israel Emiot were transformative. I would love to hear more. What did you learn from Grade, Sutzkever, and Emiot? How have these giants of Yiddish literature influenced your writing?

Emiot and I sat together for many many hours talking about poetry. He told me not to write unless I couldn’t sleep without it. I didn’t know it came from Rilke, but I stopped sleeping.

Emiot was desperate to find an audience, and a total refugee from a lost world.

You had the very unusual experience of translating your own poems, in this case from Yiddish into English. What are some of the challenges of translating yourself? What are the thrills?

I first translated the book from Yiddish to Hebrew, with the help of the late Rivka Bassman, and we discussed the limitations and possibilities for over a year. She even showed me it was possible to translate by doing a poem called “Refugees” herself. That gave me the courage to continue. But in fact there are poems I left out because they were untranslatable in Hebrew. Yiddish is a much more ironic language than Hebrew for me.

In English I was afraid of making the poems too literary, too poetic. My initial purpose in writing in English was to transmit the experience of living in Yiddish. I’m not entirely sure the English came off as Yiddish-in-English.

This Yiddish collection comes after a long career as an English-language poet. Why do you think you turned to Yiddish now? Did it feel like a homecoming of sorts?

There are experiences that could only be expressed in Yiddish. Some of them were the experiences of the refugees I grew up with. Some my parents and friends. I felt I had to talk about them before that whole world disappeared. I am now writing a series about the refugees in English, and a few poems about my experiences of Yiddish school in Yiddish.

But there is something about Yiddish that is the language of the outsider. I have always been an outsider, preferring to stand on the sidewalk of the expensive restaurant, make fun of the rich diners, and then go home and make myself a sandwich.

For Further Reading:

Yerushe by Karen Alkalay-Gut in Yiddish and Hebrew (link to complete text) https://yiddish-rashutleumit.co.il/en/our-events-calendar/934-inheritance-bilingual-poetry-book

Karen Alkalay-Gut’s website, including her Tel Aviv diary:

https://karenalkalay-gut.com/

Yerra Sugarman interviewed by Tony Leuzzi of The Brooklyn Rail https://brooklynrail.org/2023/02/books/Yerra-Sugarman-in-conversation-with-Tony-Leuzzi

Links to several Yerra Sugarman poems

https://yerrasugarman.com/poems/

Marilyn Hacker on Yerra Sugarman’s first book:

https://www.pshares.org/issues/winter-2002-03/forms-gone-yerra-sugarman

******************************************************************************************************

I hope you enjoyed this newsletter. Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

So very proud of my cousin Karen. She has made a career out of her love for poetry by writing over 30 books and teaching at the university level as well. She has even encouraged me in my quest to write some in my retirement. Her body of work is from the heart and it truly shows. She is so hip and cool and has mentored so many. So glad you have recognized her efforts here.

I bought “Aunt Bird” and can’t wait to read it. And the last paragraph of your interview with Alkalay-Gut made me laugh and want to go read her books.