The Soul in Yehoshua November’s Poetry

On his new collection--and this Sunday's salon featuring it!

I have been waiting for Yehoshua November’s new collection, The Concealment of Endless Light, just published this month by Orison Books. I know I am not alone in my waiting. November is a distinctive voice in poetry—he writes about God, love, and family, along with what could have happened but didn’t, but that doesn’t really describe it. November’s real terrain is the soul.

I don’t know about you, but I am always ready to read more about the soul. November’s poetry, whether he says it explicitly or not, is concerned with the neshama, the Hebrew word for soul, but I would say it is also interested in the broader concept of nefesh, sometimes spelled as nephesh, which appears often in the Torah. Nefesh is sometimes translated as soul, but it is also sometimes translated and understood as a living being, or life.

For example, in Leviticus 17:11 and 17:12, the Biblical verses explaining why eating blood is forbidden, the 1918 Jewish Publication Society translation initially renders nefesh as life. So ki nefesh habasar ba’dam hu is translated in verse 11 as “For the life of the flesh is in the blood.” But by verse 12, that same word, nefesh, has become “soul” in translation, with “no soul of you shall eat blood.” Leviticus 17 in Hebrew and in translation

Beyond the various meanings of the word nefesh, it’s interesting to consider that the two Hebrew words for soul—neshama and nefesh—come from breathing-in, or neshima, and breathing-out, or neshifa. But nefesh, as my mother reminded me in conversation, when I called to discuss, is actually a borrowing from the neighboring Babylonian culture—in Akkadian, nashaptum is the word for soul. And, my mother continued, ancient Hebrew can flip letters around, so nashaptum became nefesh.

I paused to think about it. Incredibly, the neighbors’ idea that the soul has something to do with breathing-out has lived on in Jewish text, language, and culture.

November’s poetry sometimes seems to me to be a translation of the layers of the soul, and its many flips through time and language. And sometimes, the structure of his poems seems to mimic a breathing-in, and then a breathing-out—as if the poems explore the two words for soul, rooted in ancientness, one describing breathing in, or neshima, and one detailing breathing-out, or neshiphah.

Fittingly, the collection opens with a poem titled “Notes on the Soul,” which begins:

November is interested in deep concepts with multiple potential meanings. He is comfortable with what cannot be remembered, and what cannot be easily explained. That “cannot remember why” in this very first poem is, to my eye, a classic example. And Jewish thought, and more precisely, Chassidic thought, including all its many questions, is a constant topic of November’s. It is the soul, the being, the life blood of his work, but you don’t need to be an expert on it to understand the poems.

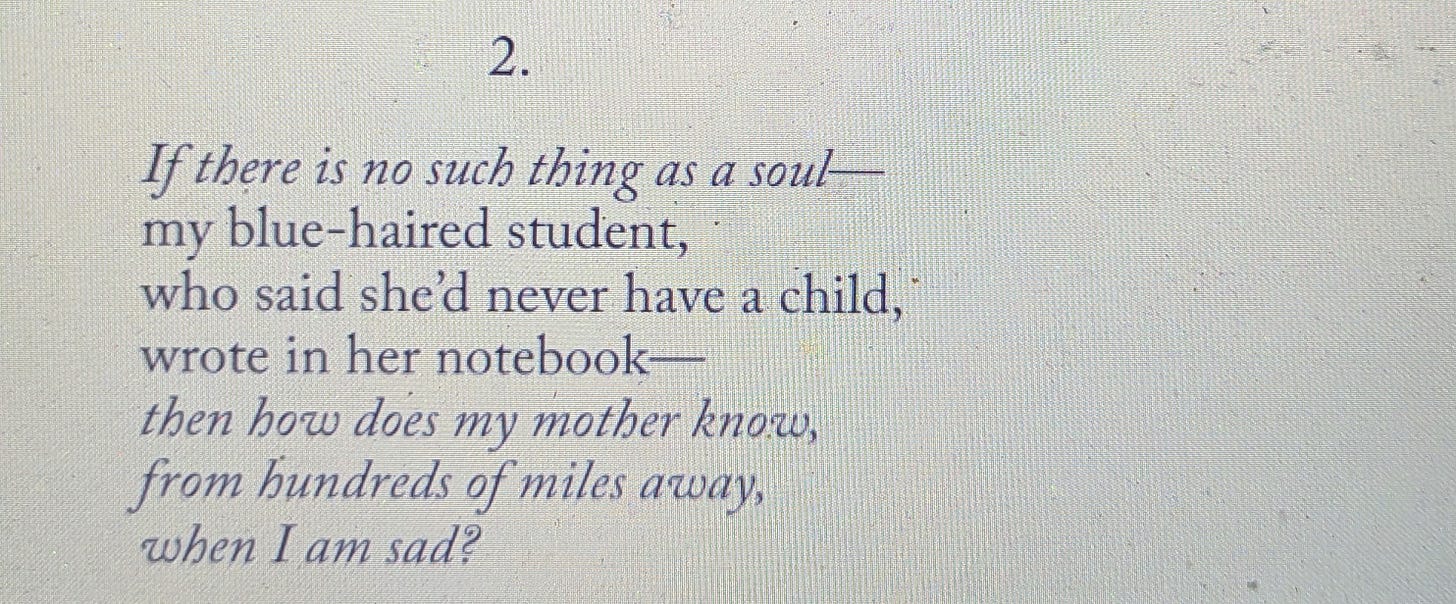

One reason that you don’t need to be an expert is that November frequently quotes and spotlights everyday people, highlighting their wisdom, and their questions. And so “Notes on the Soul” continues this way:

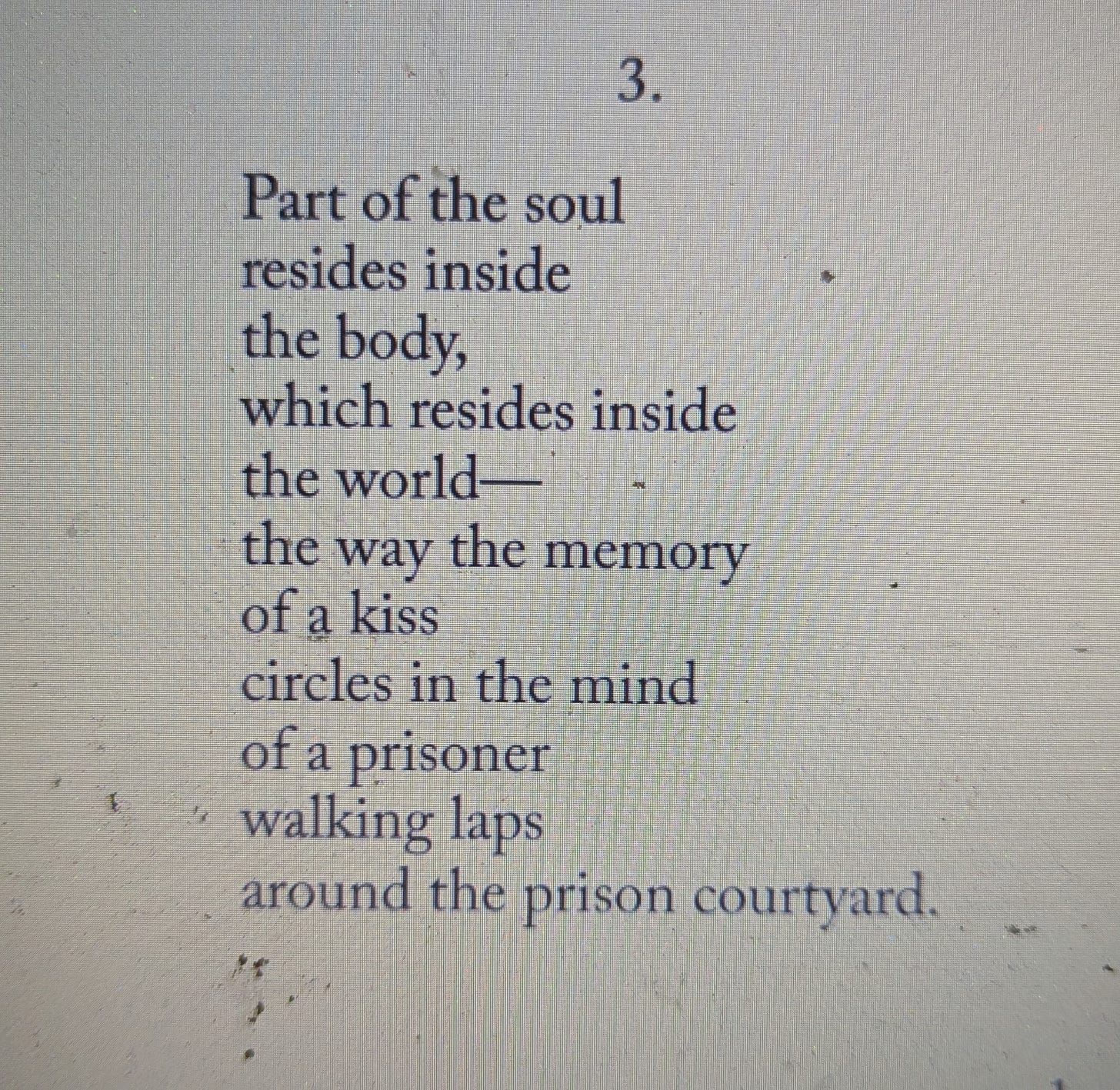

Like many of November’s poems, this poem enlarges its scope as it ends, which in this case is section 3. Another thing that often happens as November closes is that he somehow references both the past and the present.

You can hear all of that here, in the last part, which opens its arms to include the entire world:

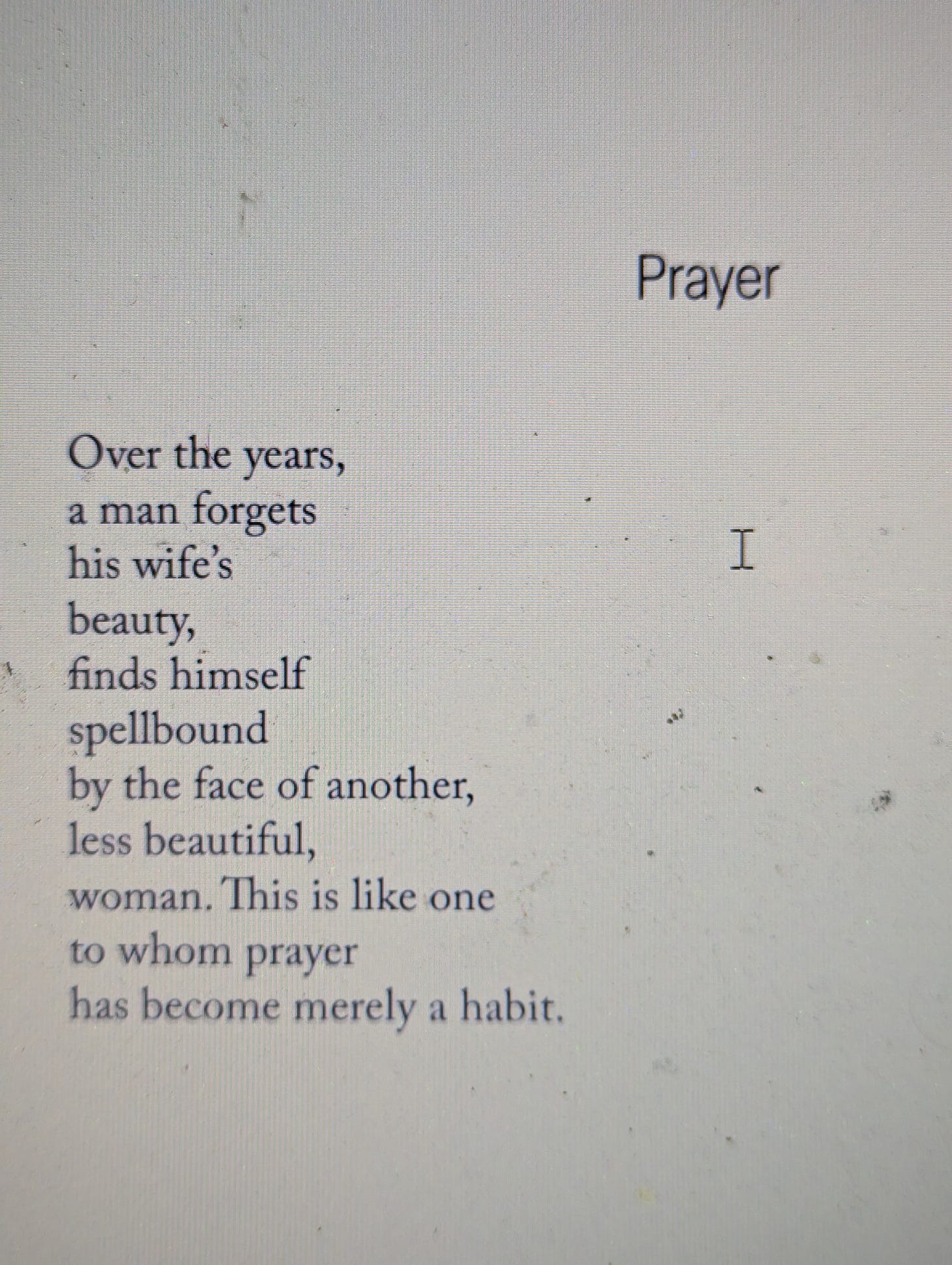

Yet that last line is about a prison courtyard, a real, tangible place. I find that November’s poem endings are often the space where he connects the so-called material world—meaning the world we all live in, including, sadly, prisons and their courtyards—with the spiritual world, which is difficult if not impossible to see and describe. I encourage readers to pay attention to his endings, which are frequently surprising, in a good way. It is there where November’s pull toward faith and deep interest in all aspects of belief comes through. Here is an example, in a very short poem on prayer:

This is Yehoshua November’s third collection, after God’s Optimism, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Poetry, and Two Worlds Exist, a finalist for The National Jewish Book Award, also from Orison Books. (November’s brother Baruch is also a poet, and the author of Bar Mitzvah Dreams.) While it may be tempting to call Yehoshua November a religious poet, he’s also, frankly, often funny. You can hear it in his titles, like “Hearing Roy Orbison in a Mikvah in Salem, MA,” And in all of his collections, he repeatedly returns to the great theme of love.

In one of the more haunting moments in this collection, which I was lucky to hear him read out loud, November describes taking a trip and forgetting to say tfilat haderech, or the wayfarer’s prayer; then he gets into an accident. That near-death experience convinces him to get a ring and propose to his wife. At their wedding, he sees that the initials of a groom who got married earlier that day are still there, reminding November that another man might have taken his place.

One of many beautiful love poems to his wife, “Forty Years,” from the new book, is an interesting poem to consider because it mentions the soul—of course! —but it also mentions time, the body, devotion, and Chassidic thought, all repeating themes.

Forty years in Jewish tradition, of course, echoes the forty years the people of Israel spent wandering in the desert. Like the best of November’s poetry, it can seem deceptively simple on first read—it is built of numbers, forty, twenty, five—but it insists on the terrain that has obsessed thinkers for centuries, the layers of the soul, and the breathing-in, breathing-out, that makes a life.

Though he is primarily a poet, I find that I also enjoy reading Yehoshua November’s prose, and learn from it. I recommend an essay he wrote for Harvard Divinity Bulletin about Lecha Dodi, or Come, My Beloved, which is sung in synagogues on Friday night. It’s a poem I love from the 16th century, by Shlomo Alkabetz, a rabbi and Kabbalist who was born in Thessaloniki, Greece, and died in Tsfat, Israel. Yehoshua November on Lecha Dodi

I often return to this section from November’s description of singing this poem in Jerusalem, as a young man:

The poet Yehoshua November, author of three collections of poetry.

“Soon, the sky overhead turned deep blue, and we sang the hymn that ushers in the Sabbath: “Come, My Beloved, to Greet the Bride. Let Us Welcome the Sabbath.” I didn’t know it at the time, but this mystical poem—especially when read according to Hasidic thought—complicates the theology that sees this physical life solely as a means to a later spiritual reward.”

Perhaps for November, this poem is the beginning of so much.

“As I hope to explain,” he continues in his essay, “the poem turns upside down a worldview that prizes the heavens over the divine possibilities of the everyday. And, for me at least, this reversal seems to run parallel to the tendency of many contemporary poets to locate transcendence and light not in the sublime moment but in the mundane.”

I recommend reading the entire essay. I also recommend reading this new collection, The Concealment of Endless Light, in the right place, or at the very least, in the right soul-space. I decided to take this book with me and read it for the first time in Jerusalem, which felt right. It felt like its soul-home. And I am honored to host Yehoshua November in a salon this Sunday, September 29th at 12 noon EST/ 11 CST/ 7 Israel time along with the wonderful poet Richard Michelson on Zoom.

Both poets will read their poems, talk about how the poems were made, and answer your questions. I hope to see you there!

Poet Rich Michelson and Senator Raphael Warnock.

Salons are a thank-you for paid subscribers who make continuing this newsletter possible. Monthly, annual and gift subscriptions are available, and I will send a Zoom link to new subscribers who sign up by 11:30 EST on Sunday. Recordings of salons are sent to paid subscribers, and a full archive of all newsletters and salon recordings is available to all paid subscribers as well.

As always, I recommend requesting the books featured in this newsletter at libraries—it’s free, it helps other readers discover books, and it can mean a lot to writers. And of course, if you are able to buy a book, I guarantee you will be happy to own The Concealment of Endless Light by Yehoshua November and Sleeping as Fast as I Can by Richard Michelson, and to read and reread these poems.

Poems in Memory of Hersh z”l

On a personal note, several of my friends are personal friends of Hersh Goldberg-Polin z”l and his family and have suffered through this year of awfulness—and were devastated by the recent news of Hersh’s murder after nearly a year as a hostage of Hamas, along with five other hostages who had suffered for far too long.

The new literary magazine Judith published a special folio of poems in memory of Hersh. I was honored to contribute two poems. You can read them, introduced by an essay by editor Rachel Neve-Midbar, here: Finally, finally, FINALLY you are free (substack.com)

The Latest on Schlubs

Finally, in this era of harrowing headlines, have you noticed that the Yiddish word “schlub” is strangely and suddenly everywhere? I wrote about the roots of the word schlub, and some possible reasons for its renewed popularity, for The Forward. Why Schlub May Be the Word of the Year

Like the Akkadian nashaptum becoming the Hebrew nefesh, the word “schlub” is another example of the neighbors’ wisdom living on, in Jewish languages.

*************************************************************************************************************

Hope you found this newsletter meaningful! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I admire Yehoshuva November's poetry and look forward to reading his new book. Your comments and deep engagement through your knowledge of Torah entice me. Thank you for this illuminating addition to your newsletter.