Three Jewish Poets Who Should Be Better Known

In honor of the Yetzirah Conference and the Sealey Poetry Challenge

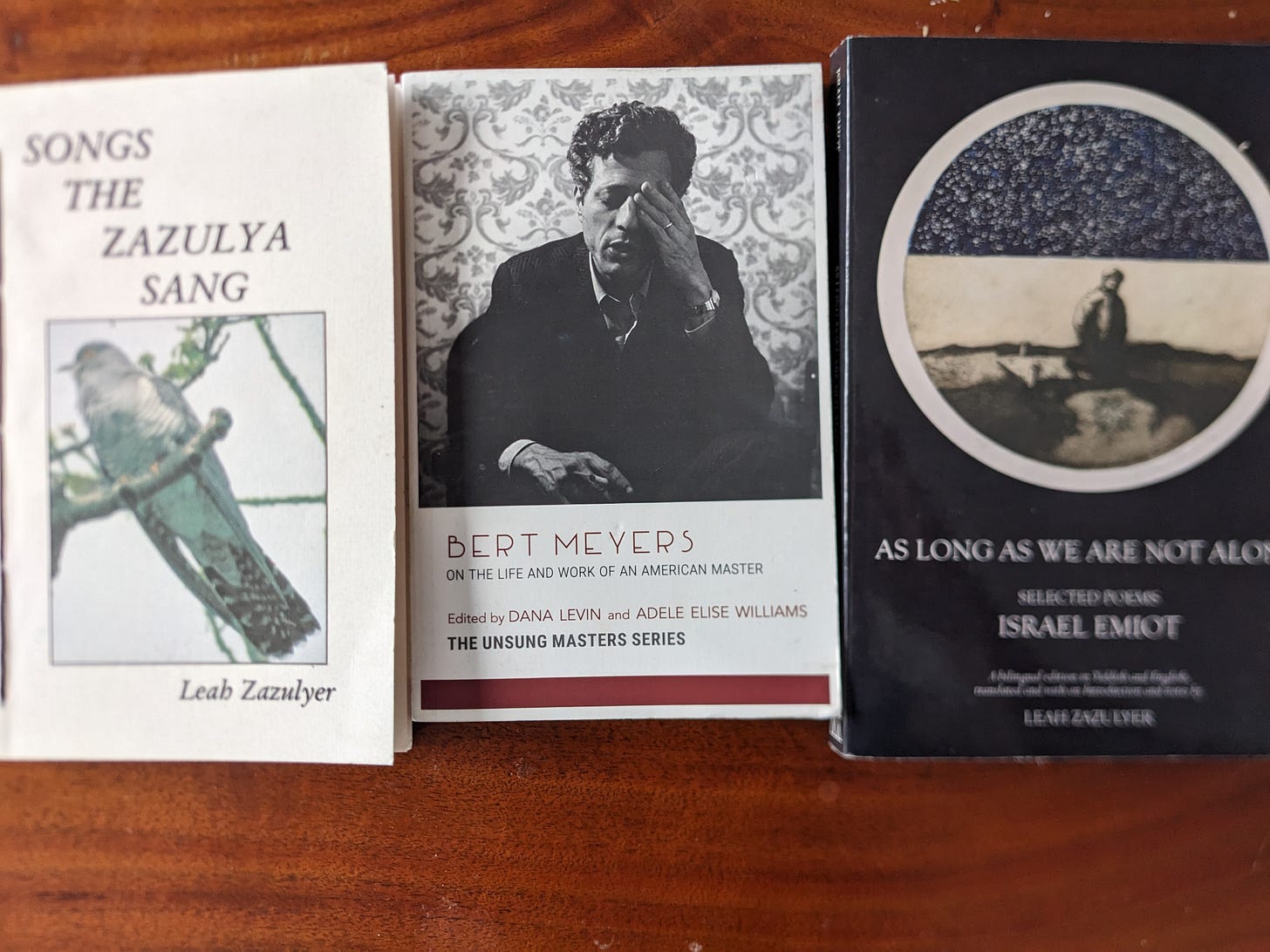

A few weeks ago at the first-ever Yetzirah poetry conference in Asheville, North Carolina, I was struck by the hunger Jewish poets have for connection and for knowledge of other Jewish poets. I want to respond to that hunger by highlighting three Jewish poets who connect to each other in surprising ways across language and time: Bert Meyers, Leah Zazulyer, and Israel Emiot.

For each of these poets, the past is always present—or as William Faulkner memorably wrote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

Bert Meyers

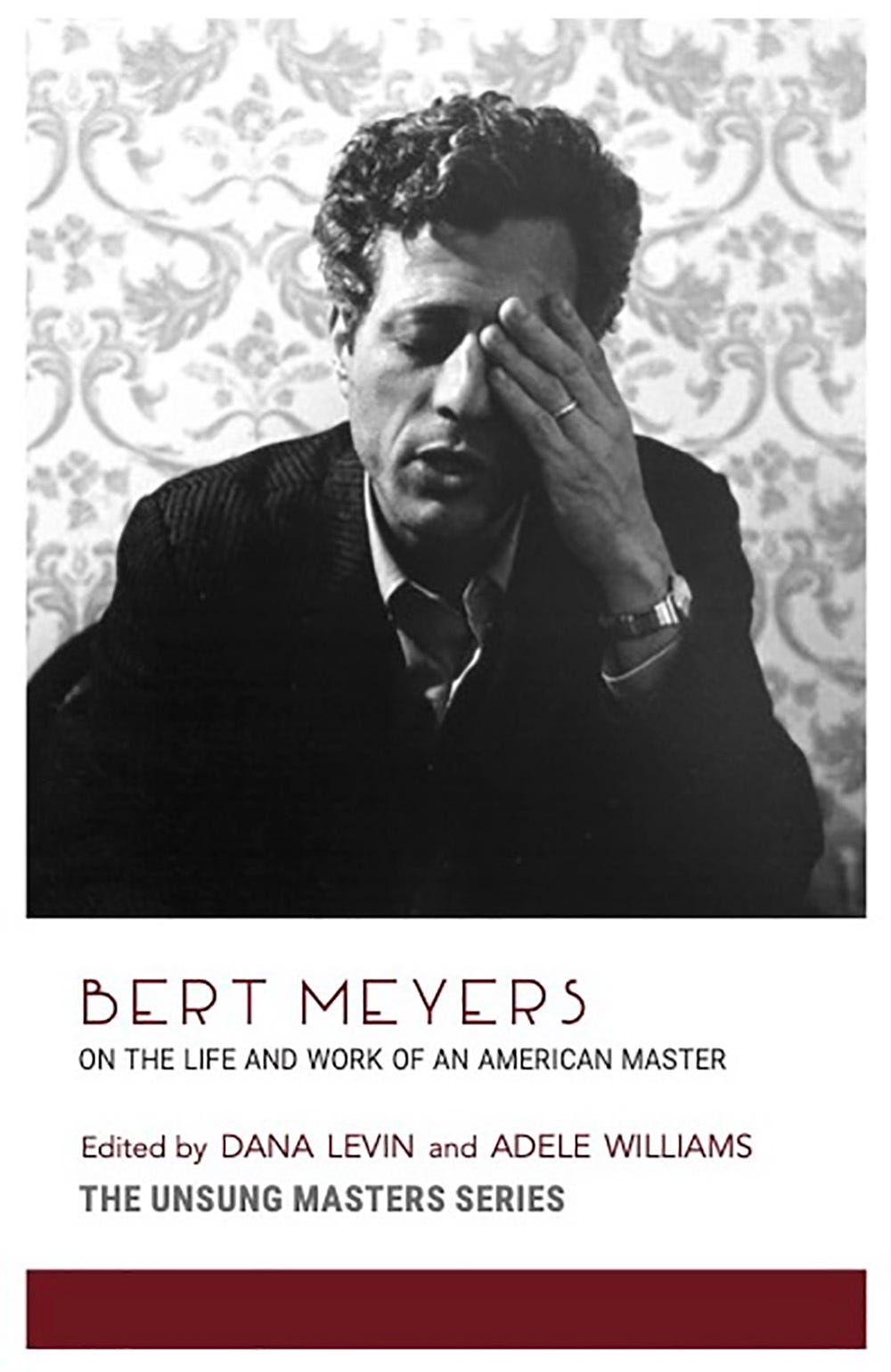

While reading Bert Meyers: On the Life and Work of an American Master, edited by Dana Levin and Adele Elise Williams, I jotted down a sentence that I have now been turning over in my mind ever since. “When I first encountered Bert Meyers’ poetry, after years in graduate school studying poetry and poetics, I realized two things: one, the tremendous number of unknown poets; two, poetry gatekeeping is real,” Williams writes.

Yet somehow, it’s always shocking to come across a terrific unknown poet.

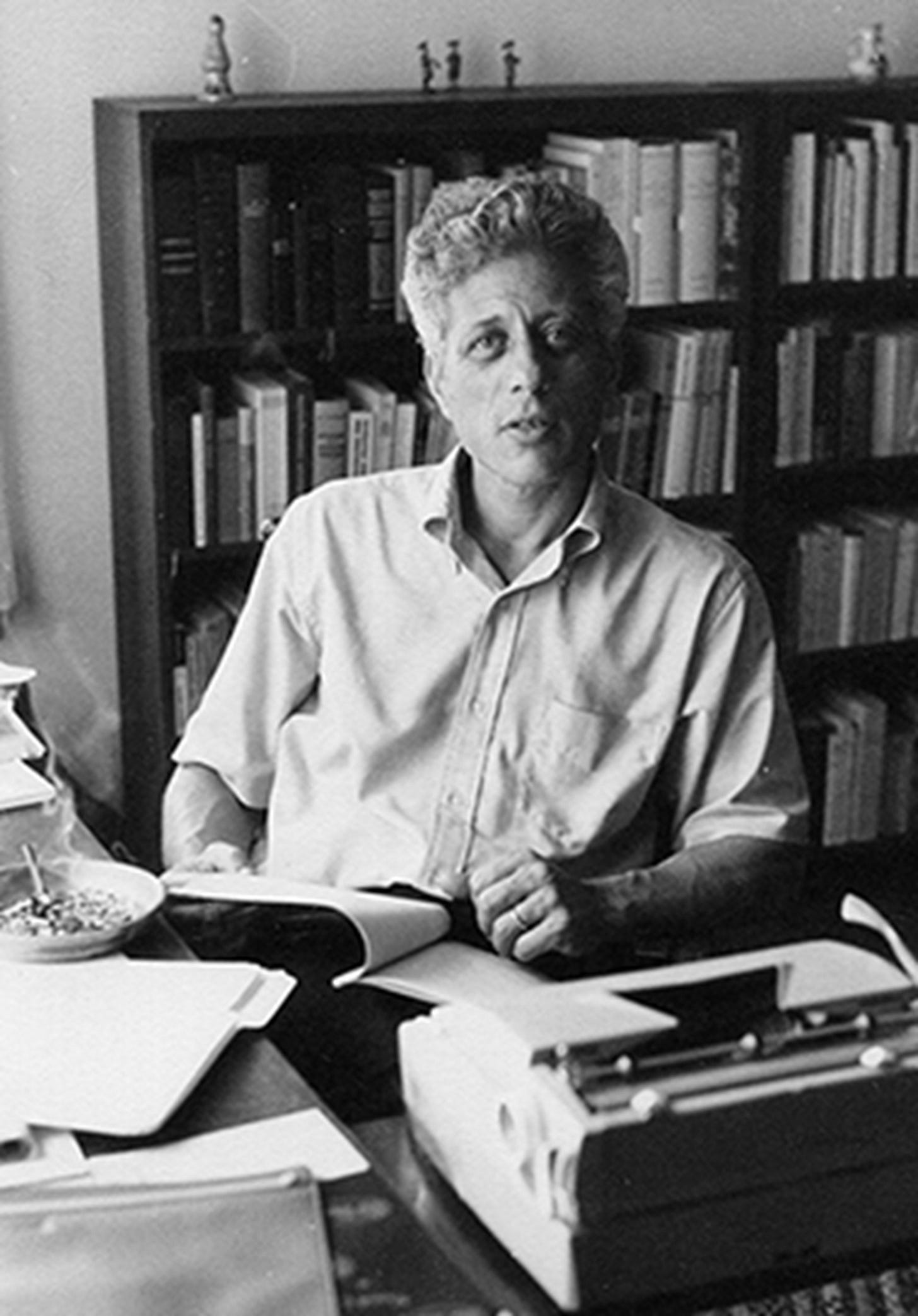

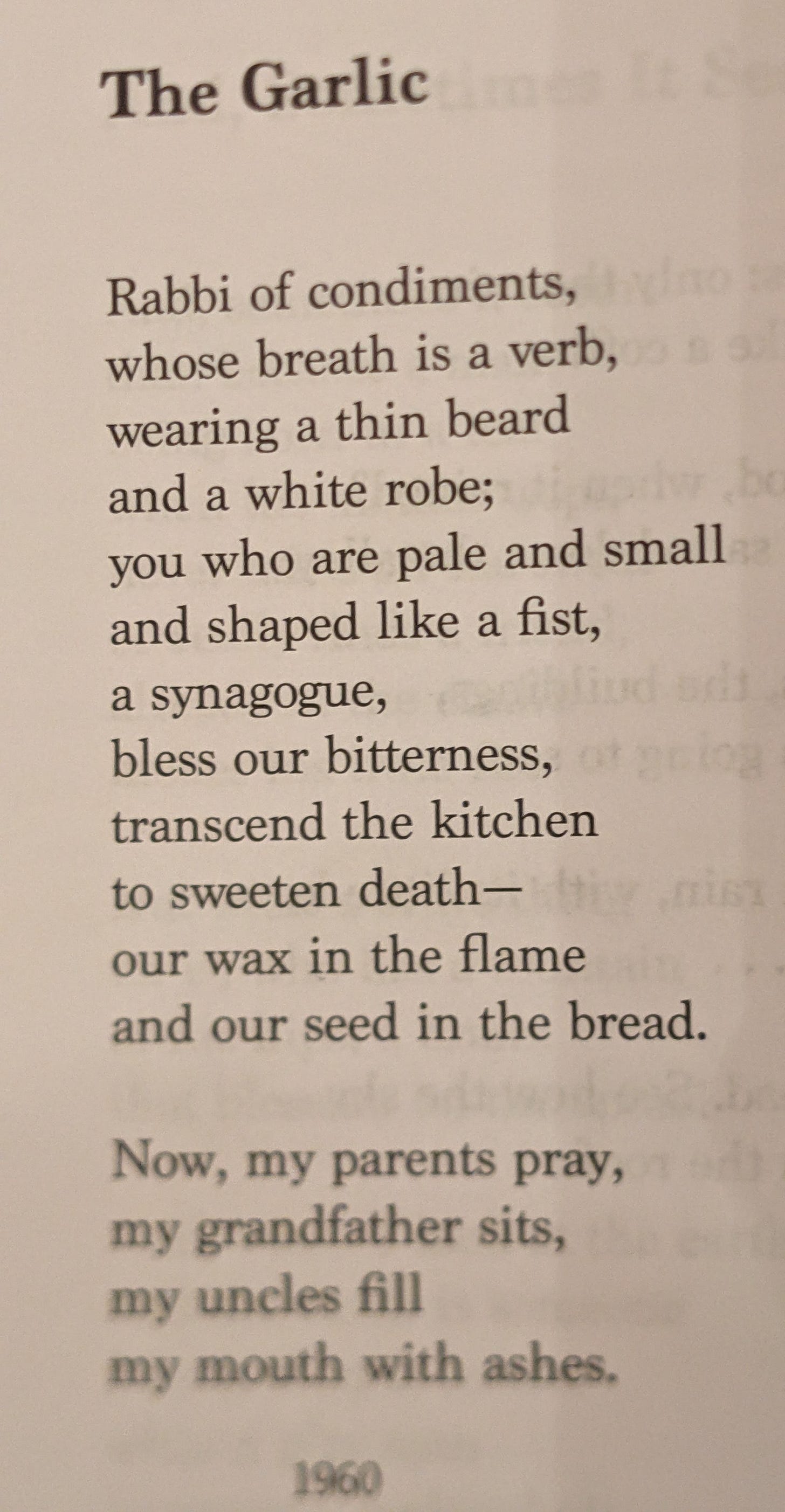

Meyers dropped out of high school to become a poet. He worked as a manual laborer—janitor, ditch-digger, sheet metal worker, house painter, and many years as a picture framer—and then became a professor at Pitzer College in the last years of his life. Meyers is often called a Los Angeles poet; he’s certainly a Jewish poet, though labels can never tell us enough of the truth. I think everyone should read and savor “The Garlic”:

I can’t get over that wonderful opening—“Rabbi of condiments, whose breath is a verb.” And the last stanza mixes the present tense with what I can only call the eternal tense.

There is a beautiful tenderness in Meyers’ work, a realness along with a comfort with a mystical dream tense. Yet his extensive experience in framing is there, palpable in the structure of many of his poems. Sometimes a single poem will have a few self-contained sections, as if each is one of, say, four pieces of wood used to hold an idea.

Consider “Cigarette,” an eight-line poem which makes fascinating grammatical choices. There are four sentences, each punctuated with a period. And each of those sentences is a self-contained story, a self-contained world.

“Cigarette,” like “The Garlic,” it uses an everyday object to consider the great subjects of who we are and who we might become. There is something of an eternal tense in the lines “You sigh as you tap/ your way to the end.”

The new Meyers book is part of The Unsung Masters Series, a joint publication effort between Gulf Coast: A Journal of Literature and Fine Arts, Copper Nickel, and Pleiades: Literature in Context. I happen to love this series because each of the books in it feels so deeply personal.

Here, it’s clear that co-editor Dana Levin—who never met Meyers—has had a close and almost spiritual connection to Meyers, whom she calls Bert, for a long time. Many of the visuals and documents reproduced in the book come from Meyers’ son, adding to the feeling of intimacy.

The book offers a sense of the man as well as the poet. I recommend it warmly.

And while The Sealey Challenge encourages reading a collection each day for the month of August, I always look for books to read slowly throughout the month. Bert Meyers: On the Life and Work of an American Master is the perfect read for that.

For more on Bert Meyers:

https://www.bertmeyers.com/

Incredible website maintained by the poet’s son Daniel.

Fire Undressed My Bones: Remembering Bert Meyers by Maurya Simon (here in Literary Matters, later included in the Unsung Masters book)

https://www.literarymatters.org/14-3-fire-undressed-my-bones-remembering-poet-bert-meyers/

“The Southern California We Knew Was Benevolent”: Letters to the LA Times on Bert Meyers:

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-07-10-bk-13775-story.html

Leah Zazulyer

Leah Zazulyer as a young woman.

First things first. What’s with that unusual last name—Zazulyer?

In case you are wondering, “zazulya” is on the word for “old cuckoo” in Old Ukrainian and Old Polish, with cognates in Lithuanian and Latvian. “Zazulyer” is Yiddish for a person who can imitate the zazulya.

Leah Zazulyer was a passionate and active translator of Yiddish poetry, and a poet in her own right. Zazulyer was a pen name. She was the very first person I ever spoke with at my first-ever American Literary Translators’ Association Conference in downtown Chicago, and I will always remember her kindness and generosity. And her energy! She was tireless when it came to advocating for Yiddish poets, and she was into Yiddish before it was cool.

Leah in a photo on her son’s obituary page for her. https://www.ianwatson.org/leah/

Zazulyer’s real name was Leah Watson, and she lived in the same house in Rochester, NY, for 53 years before her death in July 2022. I will miss her. She always knew the right thing to say, and her encouraging snail-mail missives were wonderful.

She was a fierce champion of Yiddish poets no one in the creative-writing world seemed to have heard of—but who turned out to be terrific. I thought of her as I read the Williams sentence on unknown poets in the Bert Meyers book.

I remember Leah in Bloomington, Indiana, when she was well into her eighties, insisting that the multiple plane connections she endured, along with the cold, to give a ten-minute reading of a forgotten Yiddish poet were entirely worth it. She was also a champion of women writers and translators, and a fantastic feminist.

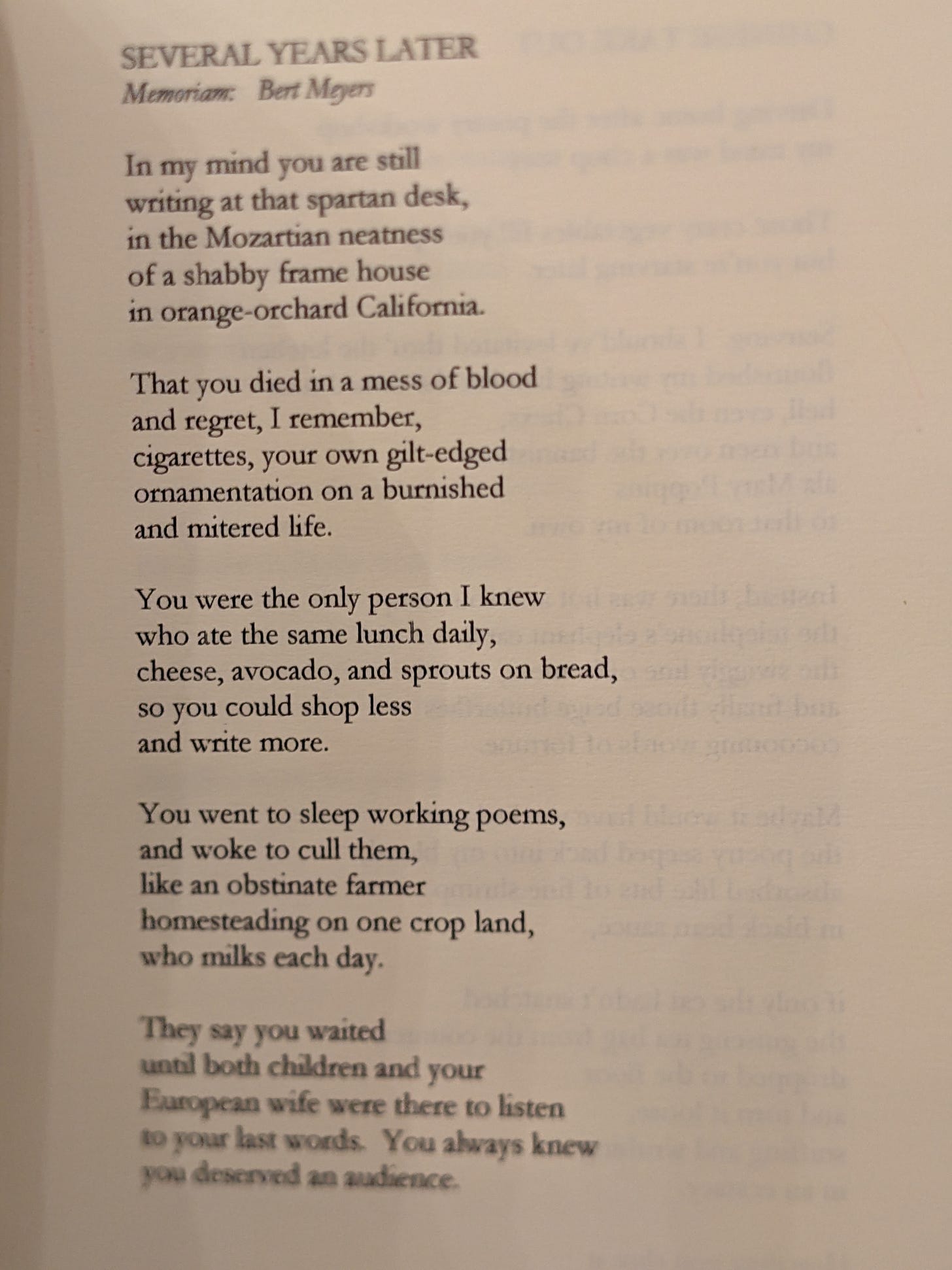

I recently found myself rereading Leah’s poems, and I was charmed to find a poem in memory of Bert Meyers in her collection Songs the Zazulya Sang (FootHills Publishing, 2007) which depicts what Meyers ate for lunch—and why.

Leah also writes that Meyers died in “a mess of blood/and regret,I remember,/ cigarettes, your own gilt-edged / ornamentation on a burnished / and mitered life.”

It was fascinating to read Leah’s take on Bert Meyers—just as I was reading his work—and to realize they knew each other. Of course.

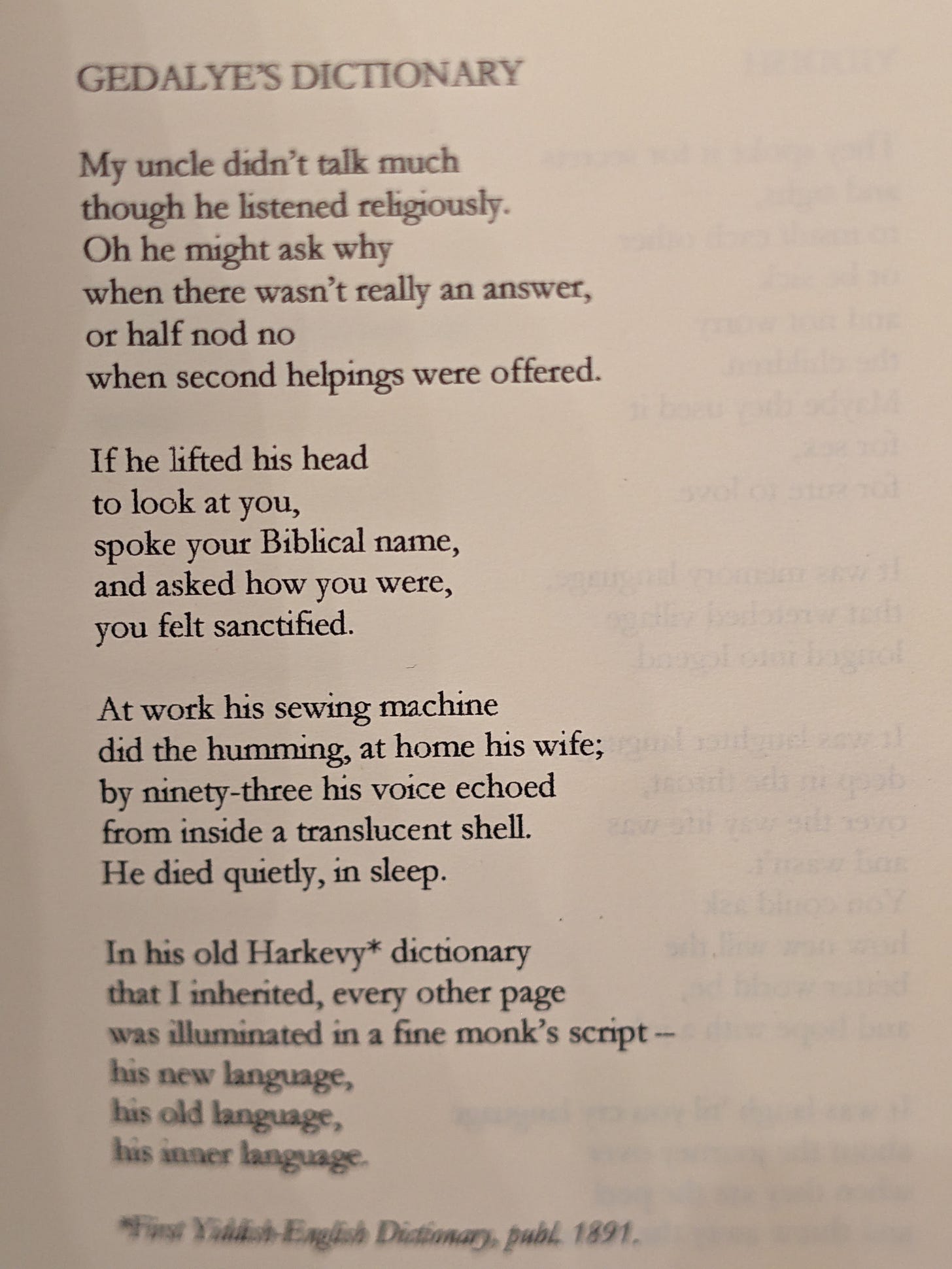

Then I came across this lovely poem — “Gedalye's Dictionary” — which connects Leah’s life as a translator with her life as a poet.

I sometimes think that a good translator knows how to convey another poet’s “inner language”. Before Leah left this world, she left English-language readers the “inner language” of the great Yiddish poet Israel Emiot—and she left many with memories of her smile.

For more on Leah Zazulyer, from her son, along with a list of her books, which I recommend. There is so much to learn from and admire in Leah’s body of work.

https://www.ianwatson.org/leah/

Israel Emiot

Incredibly, Israel Emiot was considered one of the lucky ones.

“Israel Emiot was not murdered by Stalin subsequent to the trials in 1952, now commemorated as The Night of the Murdered Poets,” Leah Zazulyer writes in her Translator’s Addendum to his collection, explaining that instead, he spent time in the gulag.

That was an easy fate compared to writers like Isaac Babel, who was shot by a firing squad at 1:30 a.m. on January 27, 1940, after a 20-minute trial, or the last of the great Yiddish poets, who were murdered after show trials.

Zazulyer is the reason English-language poets can access Emiot—she spent decades on this project. In one of the truly lucky twists of history, it so happened that after all his tribulations, Emiot ended up in Rochester, where Zazulyer lived, in her house of 53 years.

Like Zazulyer, Emiot is a pen name. Emiot was born in Ostrov-Mazoviecka, near Warsaw, in 1909. He was born Israel Goldwasser; Emiot is a combination of letters from the Polish names of his father’s initials: Meylekh Yanowski, “em” and “yot”.

Emiot was the descendant of two important Hasidic families. After his father moved to America, he was raised by his maternal grandparents as an observant Jew, but in time he became a fierce critic of Orthodoxy.

As the very worthwhile YIVO Encyclopedia entry on Emiot (YIVO spells it “Emyot”) relates, “in his critical works, Emyot often reproached Orthodox circles for their contempt for literature, and he encouraged talented writers to develop their literary abilities.” https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Emyot_Yisroel

When the Nazis invaded Poland, Emiot fled to Bialystok, in what was then Soviet Russia. After a required work assignment in Kazakhstan and an assignment as a journalist in Birobidjhan, he served seven years out of of a ten-year sentence in “a Stalin era hard labor camp during a time of renewed Soviet atrocities against Jews.”

After his release, he returned to Poland and eventually America, “where the wife and two children he had lost track of during the war now lived.” It's incredible to consider what Emiot and others of his generation went through.

Yet he kept writing. Emiot wrote twelve books in Yiddish; five are available in English translation.

Emiot’s first book, Alone With Oneself, included in the Selected Poems As Long As We Are Not Alone, is special because it is all written in a relatively obscure form; the book contains twenty-two triolets.

The edition is bilingual — Yiddish and English. I'm glad Emiot and Zazulyer made that choice, and I'm grateful that all the triolets were included.

What is a triolet?

The triolet, which first appeared in the 13th century, has eight lines in two stanzas; the second and eighth lines are the same. There is often what Zazulyer calls “an uninterrupted transition between the fourth and fifth lines, in order to produce something of a dizzying effect.”

I love Emiot’s triolet III, with its great quiet:

Note that in the Yiddish, the name of God is not spelled out—a residue of Emiot’s religious upbringing. The dash gives it away.

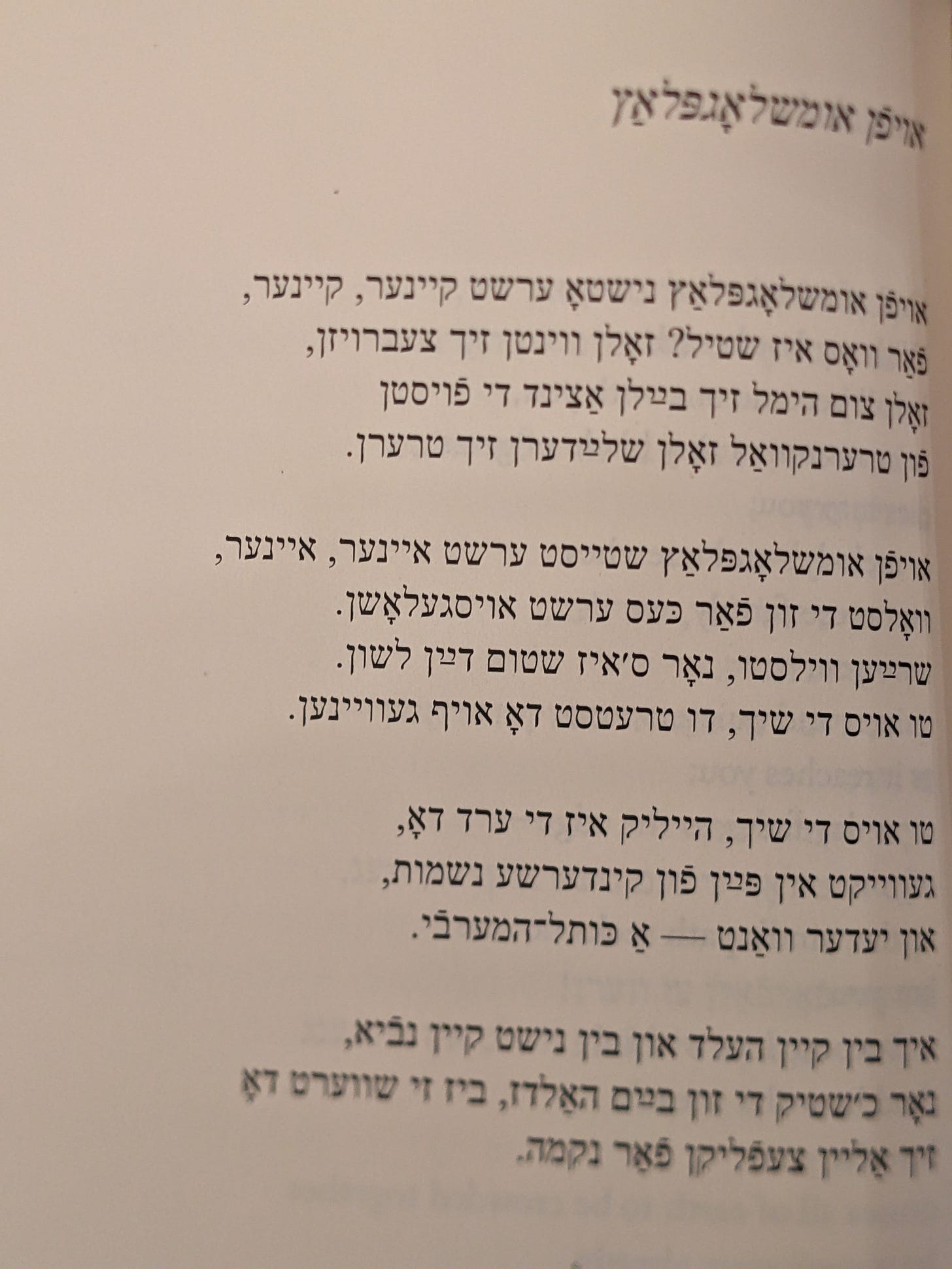

Of course, Emiot is best known for his later poems—namely, poems of the Holocaust. “Umschlagplatz,” has an interesting translation moment, as the translator, Leah Zazulyer, has chosen to capitalize a key word. (Yiddish, like Hebrew, does not have capital letters.)

And here is the Yiddish original:

I also recommend “Prayer in Snow”—which the poet Ilya Kaminsky calls one of Emiot’s best. (Link below.)

While individual Emiot poems can be unforgettable, there is something very moving about reading a large selection of his work. What comes through is stamina.

Nothing could stop Emiot’s devotion to poetry—not the Nazis; not Stalin; not the gulag; not the separation from his wife and children; and not his move to the United States, late in life. Emiot left us some of the best poetry of witness we have.

Tracking down Zazulyer’s translation of Emiot’s poems is worth it. Reading Emiot’s poetry is also an act of witness.

For more on Israel Emiot:

Two poems on the trauma of abandonment, translated and introduced by Leah Zazulyer, in Pakn Treger:

https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/pakn-treger/2020-pakn-treger-digital-translation-issue/two-poems-israel

Prayer of a Man in Snow translated by Leah Zazulyer, reprinted in Jewish Currents:

https://jewishcurrents.org/prayer-of-a-man-in-snow

Review/personal reflection about Israel Emiot by the poet Karen Alkalay-Gut, who knew him since she was 12 years old:

https://www.karenalkalay-gut.com/emiotreview.html

Israel Emiot Obituary—JTA:

https://www.jta.org/archive/israel-emiot-dead-at-69

YIVO encyclopedia entry:

https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Emyot_Yisroel

********************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! I appreciate your support of writing with depth.

Thank you for introducing me to these poets I’d never heard of!