Yesterday a man who works in my building in Chicago told me he has stopped reading the newspaper for the first time in his entire life. “You know me,” he said. “Every morning, I read the newspaper first thing. I always follow the news.”

But he said he can’t read any more, because he’s too heartbroken.

“We are living in a dystopian society,” he said. “I can’t read. I can’t listen. I can’t even watch my favorite news show.”

I keep hearing from friends who are too tired to do essential things in their lives. I read a piece in The Chronicle of Higher Education (free to read, as long as you register) titled “Higher Education Is Exhausted", about the large percentage of professors who feel extremely overworked and want to quit.

I have 76 students this term. And I know I am behind on this newsletter.

I have also been awake, late at night, watching mobs surrounding hostages who were held for nearly 500 days by Hamas or Islamic Jihad. For that entire time, I have been watching the Israeli news at night.

I recently wrote about the difference in English-language news coverage and Hebrew-language news in an essay for The Forward. It’s something I wanted to write for a while—and finally did. How the American media failed — and is still failing — in its coverage of Israel and Gaza

Today marks 500 days that the hostages are in captivity, 500 days since this horrible war began.

Still Life with Water

In a time like this, we all need poetry. I find myself craving it, and so I have been spending time with Tikva Hecht’s debut poetry collection, Tashlikh, which is both meditative and wild. It is divided into three sections—"Falling Bodies”; “Configurations of Worship”; and “Songs of Creation and Its Infidelities”. I think these three section titles give a good sense of the book, and of Hecht’s approach as a poet.

Poet Tikva Hecht. Photo Credit: David Waldman.

Tashlikh is an annual ritual that many perform on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, but that can be done until the last day of Sukkot. It involves casting pieces of bread into the water, to symbolize sins. As Hecht describes it in the notes, “crumbs are thrown into a body of water to symbolize the desire to discard sins as easily.”

Tashlikh was published by Ben Yehuda Press in 2024.

Many of these poems resemble a casting-out of bread on the water. They roam across the page, and they often symbolize something. For the uninitiated, the “Notes” at the back of the book can be helpful. For example, they will tell you that “I dream a dream and do not know its meaning” is from a prayer recited on Rosh Hashanah.

Tashlikh has been out in the world for just a few months. If you go to Tikva Hecht’s website, take a look at the bottom of each page: you’ll see the words said before the Amidah prayer. To me, this highlights how close to prayers many of her poems are.

Hecht earned her MFA in creative writing from UC Riverside. She also holds an MA in philosophy from the New School for Social Research, and a BA in Judaic studies from Yeshiva University, with a focus in Talmud. She currently serves as the editorial director at Aleph Beta, a nonprofit media company, where she produces the podcast A Book Like No Other. She lives in Toronto, Canada.

I can feel Hecht’s education in Talmud, philosophy, and creative writing in these poems. But I can also feel the sheer exhaustion many of us feel right now; maybe it can be called a spiritual exhaustion. The beautiful poem “Still Life with Water,” which to me echoes the title of the collection, acknowledges difficulty. But when I read it, the phrase mayim chayim—or living water, also echoes in my mind.

“These days are rough,” the poem begins.

Yes, they are.

I love the poem’s ending. There is the imperative, the command—”tempt me.” And also a tentative answer: “Maybe they will tempt me, maybe I will move.”

A Poem with a Long and Memorable Title

Many of Hecht’s poems are on the long side. But this one is very short—yet it has a beautiful long title. I love the idea of an “angel made of my thoughts.” Whatever you do, don’t skip over this title.

I keep thinking about the last three lines. ‘I know why/ you call it courage/ to be so afraid.” This is a time when we are all seeing portraits of fear and portraits of courage, and perhaps they are sometimes one and the same. I do wish I felt Hecht’s sense of knowing—for me, this has been a time of not-knowing.

I want to highlight one last poem.

Like so many of Hecht’s poems, it has a a gorgeous title. This time, it’s shorter, but still unusual: “Apology in the Form of Dissent.” It’s about the past and the present, and it’s about love—specifically, how it can be “embarrassing to love.”

I keep thinking about “in the sense/ it is decent to want/ less”, not just in a personal context, but in the context of a country, a community, a world. Should we want less?

I don’t think so.

I hope we continue to want. and I hope all of us can have the experience of living “untamed,” as the first line of this poem describes.

As always with Hecht’s poems, something turns at the end. In this case, she mixes thinking with feeling, which is another hallmark of this collection.

Special One-Time Class on Revision!

I am always revising—and I wish we would talk more about revision. I spent ten years on The Grammar of God, and far longer on WOLF LAMB BOMB. An essay I worked on for eleven years, titled “A Duck with One Leg,” was published by The Gettysburg Review and reprinted in Longreads; it was named a Notable Essay by Best American Essays. Working on that essay taught me a lot about how to revise—and how to stay hopeful while revising.

I wanted to share what I have learned with writers. This class will cover both prose and poetry, and I’ll bring in examples of each. You can register here: Register for Revision Strategies for the Exhausted.

And yes, it will be recorded. Luke Hankins at Orison Books, the publisher of my debut collection, WOLF LAMB BOMB, will collect any questions from those watching the recording after the class has ended. This class helps support the press and makes it possible for new collections to enter the world. If you have been working on something for a long time and need some help going forward—this is for you. Hope to see you there!

Next Salon in March—Chava Rosenfarb Spotlight

I have been wanting to give readers a special window into the amazing work of Chava Rosenfarb, the great Yiddish writer whose collected short stories were recently re-published in translation. I wrote about Chava Rosenfarb for The Forward in a piece titled Why This Is the Year to Celebrate Chava Rosenfarb and I also explored her work in this newsletter Love and Destruction: Reading Baldwin and Rosenfarb. But I still can’t stop thinking about it.

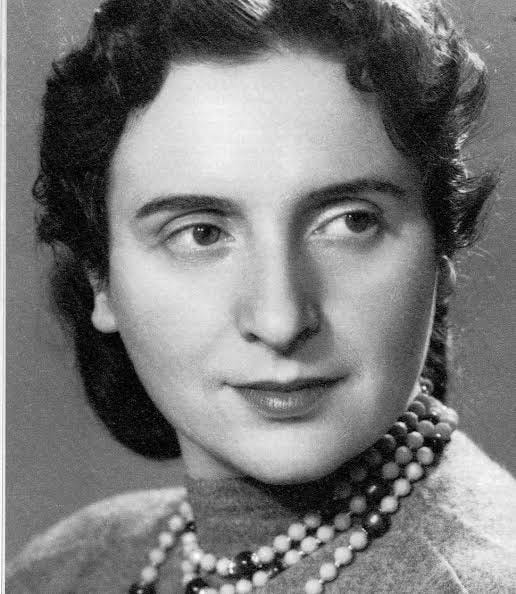

The great Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb

I have invited two very special guests—Goldie Morgentaler, Chava Rosenfarb’s daughter and the translator of these unforgettable stories, and the incredible Yiddish scholar, translator, and poet Kathryn Hellerstein to talk with us about an individual Rosenfarb story and update us on how Rosenfarb is being celebrated in her home city of Łódź, Poland, where she was born in 1923.

To me, the city of Łódź embracing Rosenfarb is one of the truly amazing developments in the world of Jewish literature.

A mural depicting the great Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb in Łódź, Poland, 2023. Photo credit: Kathryn Hellerstein.

Rosenfarb’s main subject was the Holocaust; she was a survivor of the Łódź ghetto, Auschwitz, and Bergen Belsen. But I think she is really a writer of survivors’ afterlives. There is no one like her.

Salons are a thank-you to paid subscribers, and highlight writers, thinkers, and translators who deserve more attention. Annual, monthly, and gift subscriptions are available, and include access to recordings of all past salons and archived issues of all past newsletters. Rosenfarb’s great work “Edgia’s Revenge” is worth the time away from today’s headlines, and will add meaning to your life.

Stay tuned for more details—and hope to see you soon!

***********************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.