For a long time, I was embarrassed to admit how long I worked on pieces of writing. The Grammar of God took ten years, and WOLF LAMB BOMB took more than twice as long. And just because something isn’t a book doesn’t mean it can’t take me years, or more accurately, decades. But somehow, lately, I don’t feel as embarrassed as I used to feel about my slowness. Instead, I have embraced the idea of time as a character.

This is an idea I got from Francine Prose, the author of 22 books of fiction. In addition to books, she also manages to write many wonderful book reviews and essays. Years ago, I read and was deeply moved by her introduction to William Trevor’s Fools of Fortune, in the Penguin Classics series.

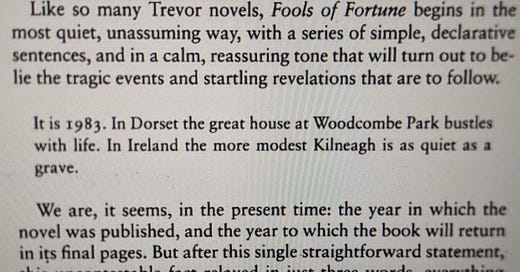

What is beautiful about the introduction is how Prose shows what time means in Trevor’s fiction:

Of course I loved this observation. I love how closely Prose reads the opening to Trevor’s novel, and I love how she sees parallels to Genesis. I spent years thinking about how to convey time as it is conveyed in Bereishit, sometimes translated as “Genesis,” when it’s a book title, and otherwise often translated as “in the beginning.”

I can’t say that I thought of Genesis when I read Trevor’s opening. Fools of Fortune. For starters, unlike Genesis, this novel begins with a precise date. A moment in time—as opposed to the beginning of all time.

But I understand Prose’s argument about contrasts, and I definitely understand her overarching idea—the importance of beginning with time.

“It is significant that the first statement in the book is a reference to time, and that the first chapter has so much to do with history and generations. For one of the most striking things about the book is the extent to which it takes time as its subject,” Prose writes.

Francine Prose, photographed by Stephanie Berger.

Time as the Most Interesting Subject

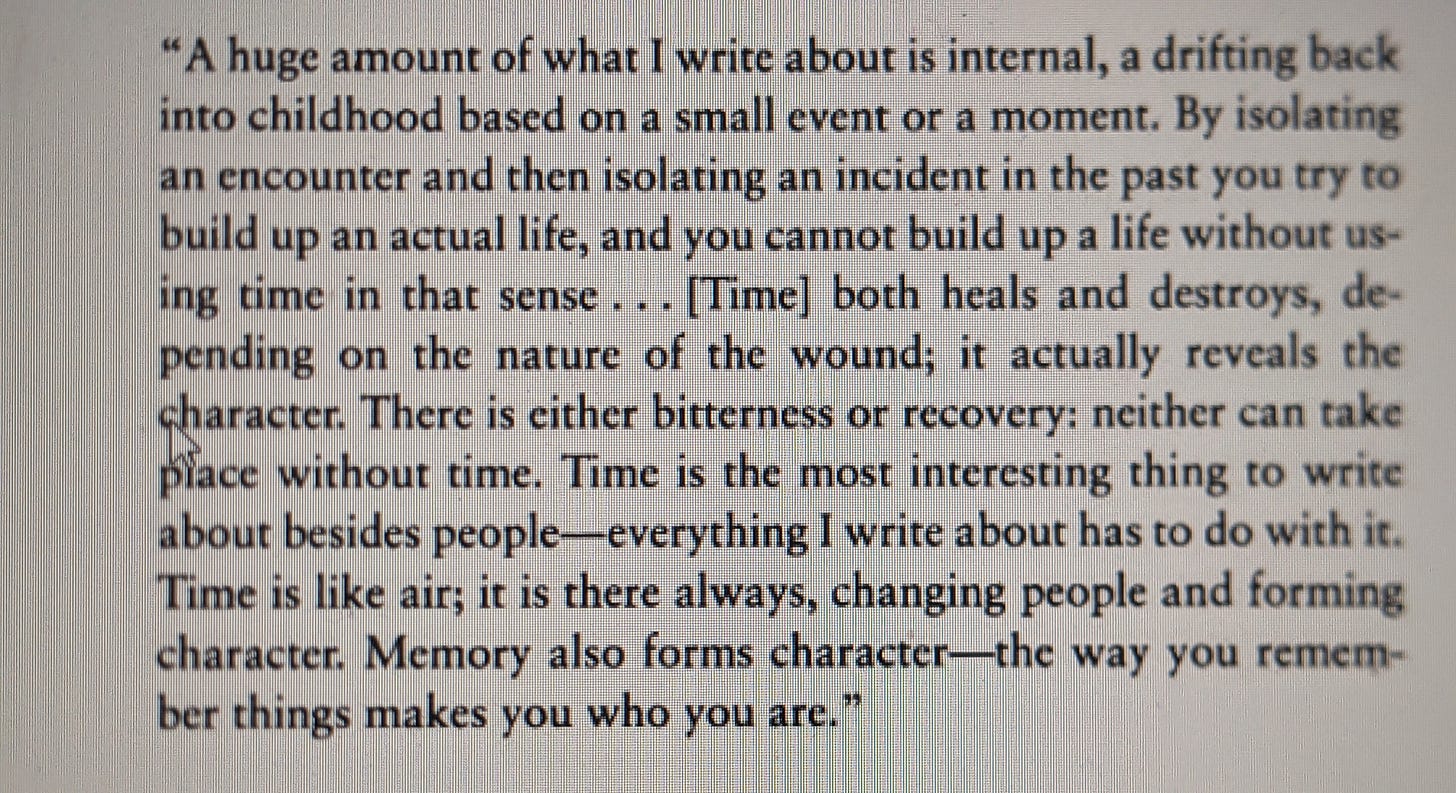

So is that time as subject? Somehow, in my mind, it morphed into “time as a character.” Maybe, to be fair, the idea of time as a hugely important force is Trevor’s idea, too. In an interview with The Paris Review in 1989, which Prose quotes in her introduction, Trevor said that time is “the most interesting thing to write about besides people.”

The whole passage is fascinating, but it gets especially fascinating at the end.

Ahah. It’s this quote that got me thinking that time is a character. “Time is like air; it is there always, changing people and forming character.”

Then Trevor points out that the other thing that matters is how we remember time—in other words, memory.

“Memory also forms character—the way you remember things makes you who you are.”

For further reading: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2442/the-art-of-fiction-no-108-william-trevor

The late, great Irish short-story writer, William Trevor.

Accepting That Time Was Required to Finish

I have been thinking about both Trevor and Prose, and both the fact of time and the memory of time, as I try and finish a few projects that all took many years but that (mercifully) seem to be ending now.

This week, The Southern Review published a 25-page essay of mine that I worked on—off and on—for twenty years. I started “Esther on the Eve of War” at about the time the Iraq War started, as I was watching American troops make their way across the Midwest. I never could have imagined that it would be published on the eve of another war.

I wrote this first page as a graduate student, new to Iowa:

The essay moves to Postville, Iowa, home of a kosher meatpacking plant, the lead-up to the war in Iraq, and the death of a friend of mine from smoke inhaled from the garbage pits outside Abu Ghraib. I didn’t know that friend when I started the essay; I also didn’t know that Iowa would suffer a great flood, that the Iowa City synagogue would relocate, and that America would change to a degree that I could not imagine.

In other words, what happened to this essay was time. But I was embarrssed to admit how much time it was. This is what I wrote ten years after I started:

“It is painful and embarrassing to continue to write about the war of being a woman within Judaism, because the war never seems to end. It is also deeply painful and embarrassing to realize that America is still in Iraq, ten years after I began working on these pages, thinking I would record a limited moment in time: the eve of war.”

By the time I was able to write that, I was also able to write—briefly—about all the time that had passed. William Trevor was right; it’s not just time but the memory of time.

“I could not imagine that America would spend the next decade with soldiers on the ground in the Middle East. I also could not imagine that an Iowa boy I did not know then, named Joshua, was at about that moment—at around the time that I was driving to Postville and back—enlisting in the military, and that ten years later his story would keep me up at night, and send me back to these pages—pages I had abandoned.”

But that wasn’t the end of it. Ten years after that, I returned to the essay. For those counting, that’s twenty years—a lot, even for me.

For further reading: This essay is available in print, but not online—unless you have institutional access, which will let you download a PDF through Project Muse: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/908387. You can purchase the issue here from The Southern Review: https://thesouthernreview.org/issues/detail/Autumn-2023/266/

Encouraging Slowness

Is slowness so bad?

As the headlines blare with a new war—and as, once again, as during the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, it is hard to think of anything else—I find that I am surrounded by quick takes. Numbers and statistics are immediately accepted as certainties, no matter what the source. A single quote is taken out of context, again and again.

A moment of anger is amplified, creating more anger. More burning.

I found myself taking a road trip to get away from the headlines, just as I did decades ago on the day I started writing “Esther on the Eve of War'“. And as I drove, I tried to focus on the beauty of the wide sky, and the gorgeousness of mile after mile of drying corn in late October.

When I started “Esther on the Eve of War,” there were no smartphones. No social media. There was just what I had now—a crackling car radio. As I edited, decades after I started, I left the passages about using an actual paper map on the road trip that sparked the piece. I threw out most of my paper maps, but I am still very fond of paper and slowness.

Slowness lets us look and listen more closely, more carefully, and for all those writers and readers out there who are feeling slow, I want to say that slow can be an important and in fact, essential, speed to operate on.

A note to Chicago readers: Mark your calendars for a poetry coffee at Edge of Sweetness at 6034 N. Broadway on Sunday, November 5th at 3 p.m.!

************************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Looking forward to your essay. I loved this reflection, and it reminds me to be less impatient with myself.