More Thoughts on Prayer as Poetry

On one of the most beautiful and terrifying and poetic prayers.

As soon as I walked out of the airport and opened the door of the car, happy to come home for Rosh Hashanah, my father told me that he did not agree with my choice of favorite prayer. Instead, he made a case for his favorite prayer—which, to be fair, is also beyond beautiful.

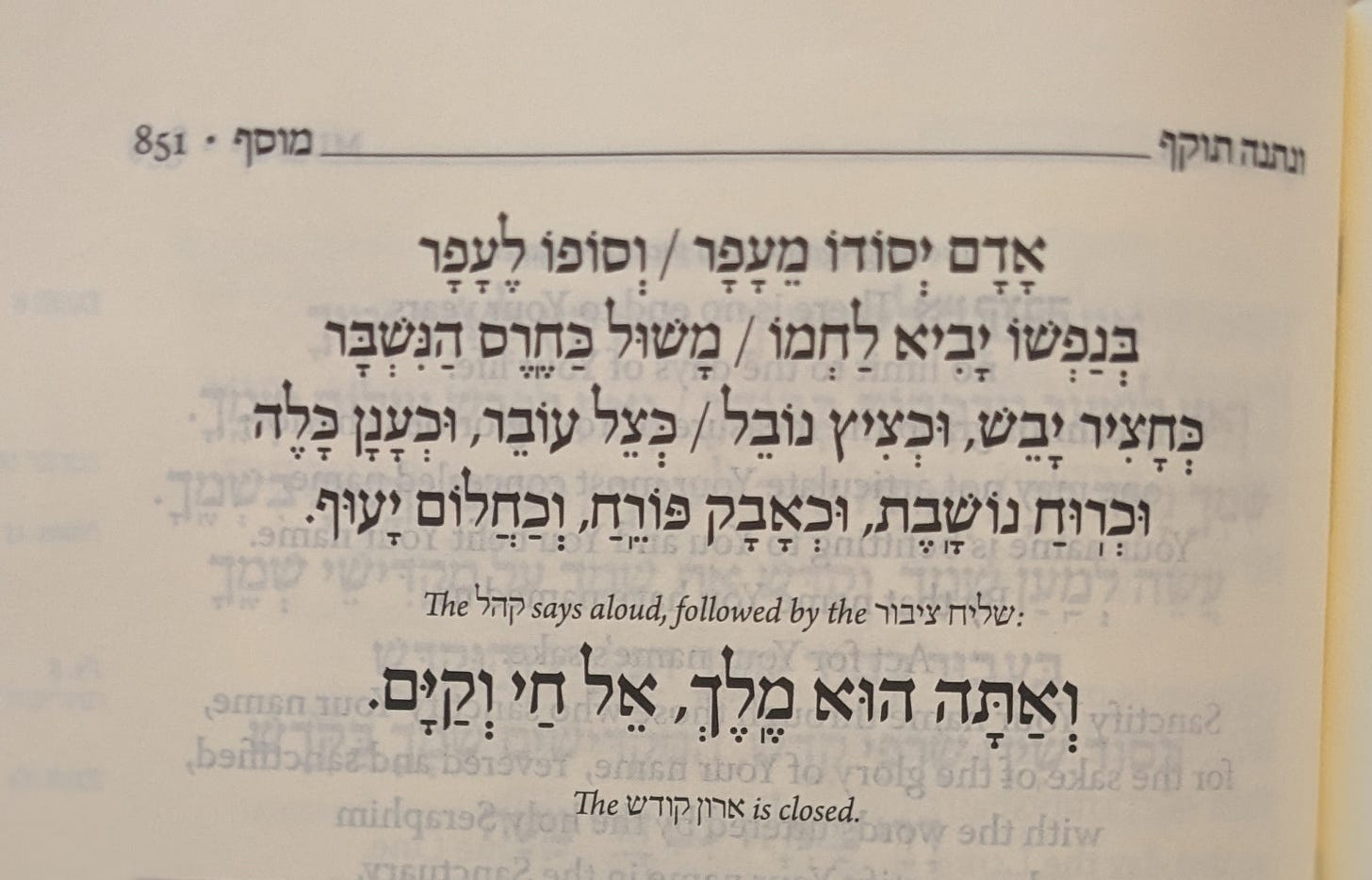

My father loves the end of u’netaneh tokef, which is arguably the centerpiece of both the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur prayers, and which directly addresses the harrowing subject of who will live and who will die. Here is the unforgettable end of the prayer, in Hebrew—you can see it is arranged as a poem:

The title of the prayer Unetaneh Tokef can be seen in the top right corner of the page.

How can anyone translate the title of this very old prayer? Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks z”l tries: “let us voice the power”.

Hmmm.

Haaretz, which must have some intrepid translators, bravely went with “let us recount the power of the holiness of this day.”

Every other translated machzor, or holiday prayer book, in my library just transliterates it, a choice I totally understand and empathize with.

What Is Man?

The lines my father loves—the four last lines, all of them poetry, and all of them sung in a haunting melody—are all about the ephemeral nature of man. In Hebrew, the first line is built around the “phay” letter, so it has the “ph” sound threaded through it. These lines describe man as a broken shard, a fleeting shadow, a dream that flies away. They break my heart every year.

Here are these famous lines in the translation of Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, z”l:

Man is founded in dust/ and ends in dust.

He lays down his soul to bring home bread./ He is like a broken shard,

like grass dried up, like a faded flower,

like a fleeting shadow, like a passing cloud,

like a breath of wind, like whirling dust, like a dream that slips away.

At the bottom of the page, Rabbi Sacks devotes twelve paragraphs of commentary to the line “Man is founded in dust and ends in dust.” He begins like this—“Life is God’s question. We are his answer.”

You can see why I was very happy to purchase his translation and commentary.

The machzor, translated by Rabbi Sacks z”l—with a commentary.

Though readers may be fasting as they read on Yom Kippur, Rabbi Sacks does not let the reader rest.

“We have only one life, and however long it is, it is a mere microsecond in the history of the universe. The greatest decision we will ever make is how to use our time, how to create something of beauty and meaning and love that was not there before,” he writes.

Responsibility and History

Like the prayers themselves, Rabbi Sacks often moves into the subject of personal responsibility.

“Something momentous is born every time a human being takes the decision not to rail against the evils of the world but instead to do something to alleviate them. This ethic of responsibility is Judaism’s great contribution to the world. No faith has asked more of its followers. None has taken so high a view of human possibility. We may be mortal but we are God’s partners in the world of creation, and that is as close to immortality as we will ever come,” Rabbi Sacks z”l writes.

This prayer was long attributed to Rabbi Amnon of Mainz, who lived in the eleventh century, and died a martyr’s death after his absolute refusal to convert to Christianity. I was taught a gruesome version of this story in school—that the prayer was first uttered by a man whose arms and legs were cut off and who was wheeled before the aron kodesh, the ark.

But when unetaneh tokef was found in the ancient manuscripts of the Cairo Geniza, it was clear that it was far older—maybe even from the sixth or seventh century. It’s incredible to consider just how old it is, and how moving it remains.

Who Is Speaking

Who exactly is speaking in unetaneh tokef, or in any prayer?

I was once obsessed with the same lines that my father loves and Rabbi Sacks clearly felt attached to, as I worked for years on a short story called “House” that never made it into the world, like so much of what I work on. (Writing, too, is ephemeral—a dream that flies away.)

The main character of that story, Chava Blau, whispers one of those lines into the ear of the matchmaker, whom she has begged to help her only daughter. “Man is like a fleeting shadow, like a passing cloud, like a breath of wind, like whirling dust, like a dream that slips away.” Who is speaking those lines? The woman? God? I used to spend so much time thinking about these, and now I don’t worry at all about who is speaking.

It is simply a truth that humans are like a dream that flies away. The speaker is almost irrelevant. Similarly, the earlier lines of u’netaneh tokef detail ways to die that may have seemed outlandish years ago, but now, seem very real, as my mother observed during our conversations on Rosh Hashanah. Plague—we got it. Floods, earthquakes—Libya, Morrocco. It’s all there, in our contemporary world.

The Ancient Meets the Contemporary

So much of the ancient remains contemporary. That is the power of very old prayers, whether or not you pray. The conversation with my father about which ancient prayer is the most beautiful, and more deeply, which best captures the relationship between man and God, reminded me of an ongoing conversation throughout Jewish history—or perhaps world history.

That conversation is about how to understand the story of Isaac, namely, the binding of Isaac and Abraham’s decisions during that episode.

What does that story say about man and God? About what Rabbi Sacks called the “ethic of responsibility”?

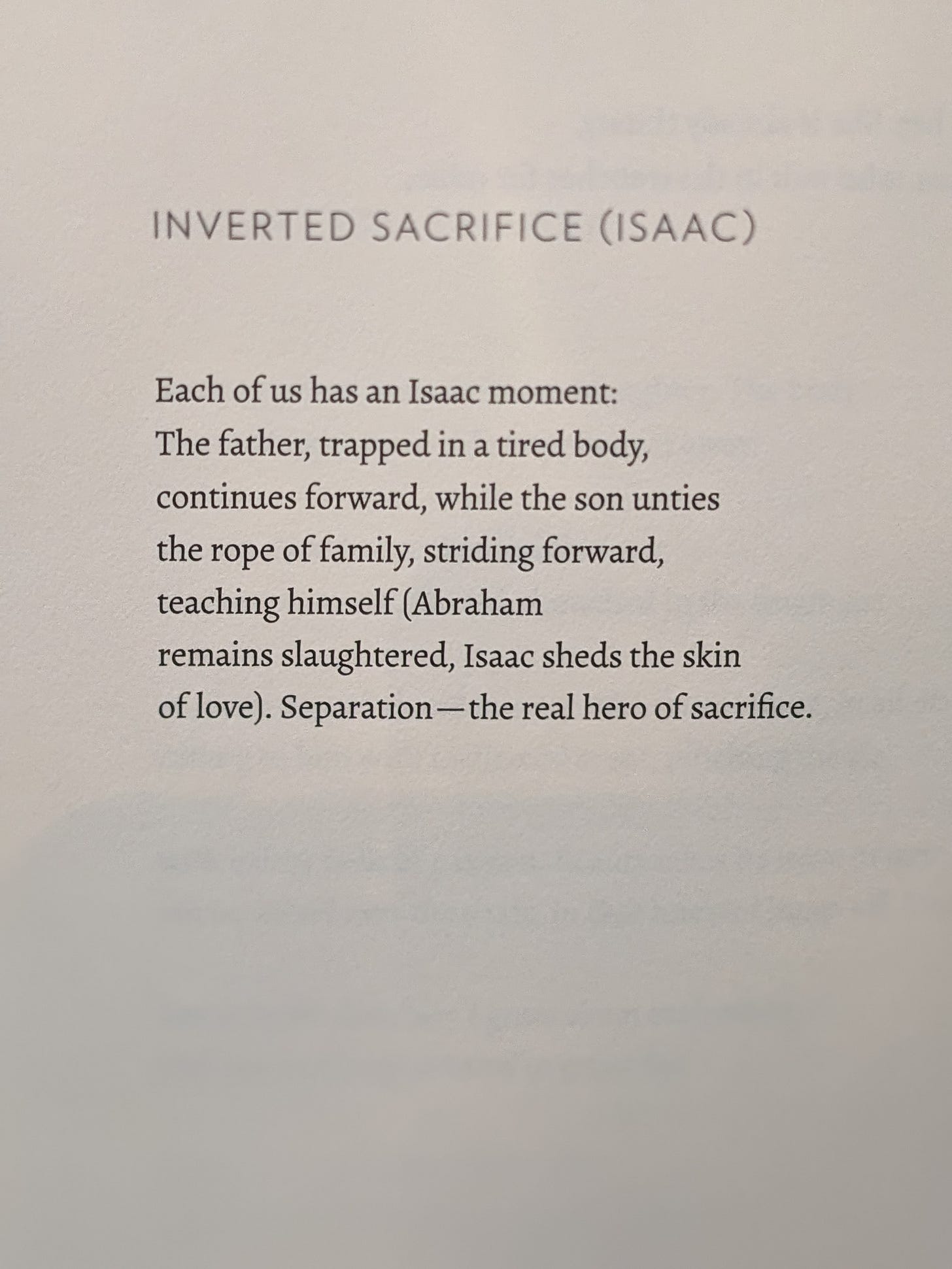

Here is a poem by the Israeli poet Yonatan Berg, from his collection Frayed Light, translated from the Hebrew by the wonderful translator Joanna Chen, that grapples with the power of a single moment and that re-imagines Isaac as contemporary.

At the Yetzirah Conference in Asheville, NC, this summer, I was blown away by this poem by Nan Cohen, written in English and published in Cohen’s collection Unfinished City (Gunpowder Press, 2017), that also considers Abraham and Isaac anew.

.

I think the beginning of the poem lives on the same terrain of the last lines of unetaneh tokef, which my father so loves. Here is “Abraham and Isaac: I” by Nan Cohen:

Abraham and Isaac: I

I have lived in tents and know how faint a trace

we leave behind us on the earth;

how, when the body fails, the soul folds

its light clothes and steals away.

But now a child sleeps in my tent;

I would raise a tower of stone to shield his head,

and yet the thought that any common stone

must outlast him provokes such rage in me

I wake all night, alarmed and furious,

seeing nothing in the dark but dark.

Somber Yom Kippur Reading

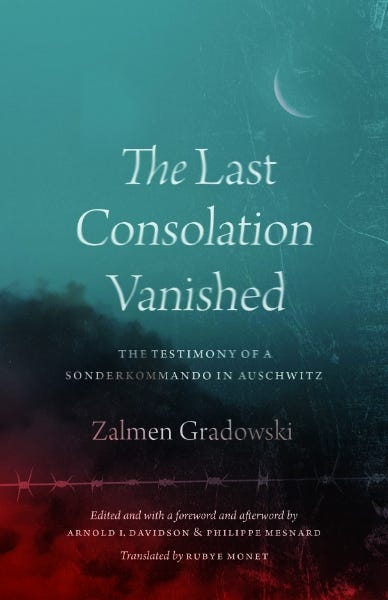

Speaking of “nothing in the dark but dark,” that beautiful phrase from poet Nan Cohen, I feel I must comment about the important publication, at long last, of a complete English translation of the memoirs of Zalmen Gradowski, who was a Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, translated from the Yiddish by Rubye Monet, and edited by Arnold I. Davidson and Philippe Mesnard, published by The University of Chicago Press.

.

Something my father likes to talk about is how the prayers never change; the Holocaust, for instance, has led to no change in the Yom Kippur prayers. My mother, on the other hand, is moved by the fact that her grandmother and great-grandmother said the same prayers. The description of Gradowski saying kaddish each day for the people whose bodies he was forced to burn in the crematoria might be something that could be added to the tefilot, by whoever makes these decisions, or something readers might add on their own.

“Gradowski was both a talented writer and a heroic warrior, whose name should be as well known in Jewish history as Bar Kokhba’s—not least because he and Bar Kokhba were equally doomed,” Dara Horn writes in The Jewish Review of Books, in a harrowing essay on The Last Consolation Vanished that everyone should find the strength to read. https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/holocaust/14402/come-here-to-me-you-fortunate-citizen-of-the-world/

“By 1942, he and his wife, Sonja, and most of their large extended families were deported to Auschwitz, where all but Gradowski were gassed and burned on arrival. Gradowski was instead forced into what the Nazis named the Sonderkommando (special force): Jewish prisoners tasked with escorting other Jewish prisoners into the gas chambers and then removing their bodies and incinerating them, work he did daily for almost two years,” Horn writes.

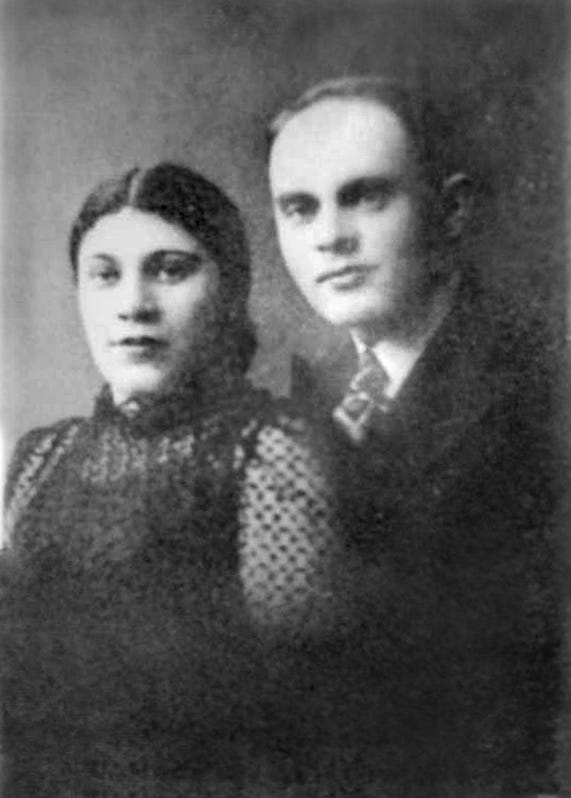

Zalmen Gradowski and his wife Sonja, circa 1934. He was murdered on October 7 1944, and she was murdered before that.

Gradowski eventually helped plan the only revolt at Auschwitz, in which he perished. He also courageously recorded what he saw and did each day, using paper and pens pilfered for him by other prisoners. His memoirs—his account of exactly how the bodies burned, and exactly what happened as women made their way into the gas chambers, and exactly what they said to their murderers and overseers—survived. As Horn points out, he writes about those who did not survive, not those who did.

His subject—the forms of death, and the fundamental ephemeral nature of man—is exactly what u’netaneh tokef directly addresses.

Here is his first paragraph:

“[Come] here to me, you fortunate citizen of the world who lives in a land where happiness, joy and pleasure still exist, and I will tell you of the abject criminals of today who took an entire people and turned their happiness to sadness, their joy into eternal sorrow—their pleasure forever destroyed. . . . Are you ready, dear friend, to begin the journey? Just one more condition I will set for you: bid farewell to your wife and child, for . . . you will no longer want to live in [a world] where such diabolical acts can be committed. Bid farewell to your friends and acquaintances, for you will certainly [after] looking at the horrible sadistic deeds from the supposedly cultured devil’s spawn, you will want to erase your name from the family of man and will regret the day that you were born.”

I was struck by that phrase—“the family of man”. Yom Kippur is about the family of man, but also, I think, about the smallness of man next to the power of God and the will of earth.

That is the subject of my father’s favorite lines in u’netaneh tokef, those four unforgettable poetic lines. It is the subject of much of Rabbi Sacks’s commentary. And I think it is also the subject of poets who are drawn, again and again, to the story of Avraham and Yitzchak, Abraham and Isaac. G’mar chatima tova.

*********************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

And on another separate note, I had the chance to sing the unetaneh tokef in the teen services when I was a kid (maybe 14?) and the melody itself, plus the performance of it, made me shake--but I also remember feeling the power of this prayer as poetry, and it’s truth that can’t be ignored or denied. I felt they had entrusted me with this ... thing ... and I was so nervous about messing it up. Afterwords I was in a kind of weird mood, very cloudy and heady, and didn’t get why people were complimenting me.

I truly welcomed this wonderful article on "the most beautiful and terrifying and poetic prayers." It has held power and my heart for so many years, grounding and centering my spiritual experience on Yom Kippur and days before and beyond....so much so that I included it as my main character's "turning" experience in Reeni's Turn, my MG novel in verse for 9-12 year olds. For her, and for me, it is the call to listen—and then perhaps take steps she (and I) have been afraid to take. "Then these words:/ The great shofar is sounded,/a still, small voice is heard./My body quiet/the words shivered into my brain, heart, arms and legs/the way music does/deep inside where it sings out,Dance!/But instead of that,/these words whispered to me/Listen!" I shiver with the impact of U'Netaneh Tokef each year, and am grateful for this beautiful post before Yom Kippur. Gemar Tov—