Celan's Masterpiece in Chapbook Form

A new chapbook offers rare glimpses into Celan's most famous and haunting poem.

Sometimes I really want to write about a book, but no matter how hard I try, it doesn’t happen. The books I cannot write about haunt me, like unopened mail, or unanswered phone calls. Occasionally the reason is that an editor, or several, said no to a review pitch—but most of the time it is because I simply do not have the hours. I am always writing, translating, and teaching, and sometimes the balance tips one way or another. I rarely get a second chance, because a book becomes “irrelevant” very quickly. Just a few months after publication, it can be impossible to place a piece, even if the writer is undeniably eternal, like Paul Celan.

Celan’s poetry is timeless at its very core. It is always looking back at us, and into us. Celan, to my ear, is in deep conversation with the prophets of the Tanach. I was so moved to come across a snippet of Isaiah in Celan’s own handwriting, in Hebrew, in the biography Paul Celan: Poet, Survivor, Jew by John Felstiner, who also translated Celan’s poems. It’s a book I re-read often.

There it is — kumi ori, or “arise, shine.”

The last two words on the page, seen here in Celan’s handwriting are from Isaiah 60:1. It’s moving to see Celan switch from German to Hebrew as he drafted a poem.

An Important Translation of Celan

Celan, himself a translator, had many translators of his work into many languages. Since the 1960s, Pierre Joris has been translating Celan’s poems into English, and his Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech: The Collected Earlier Poetry of Paul Celan, was a book I really wanted to write about.

Joris was born in France, raised in Luxembourg, and has moved between the US, Europe and North Africa for decades. He has published more than 50 books of poetry, essays, anthologies, plays and translations, and he has written extensively on Celan. I knew Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech was important, and I could get an editor to say yes, and yet the book sat on the vintage gold-and-glass bar cart in my entryway for months.

The truth is that I was so overwhelmed with getting my own poetry collection, WOLF LAMB BOMB, to the finish line that I was not able to give that big book of Celan the time and attention it deserved. In my mind, it became one of the missed books, the missed opportunities, that haunts me. I was sure I would never get another chance.

It turns out Pierre Joris also never thought he would get another chance to write about Celan and his long experience translating him. He, too, thought that was the end of a near-lifelong project. I am thrilled to report that a just-published chapbook—that small gift to readers—gave Joris another chance, and it gave me another chance to engage with Joris and his translations of Celan. I think this is another example of the outsize role that the tiny chapbook plays in the history of poetry—which of course, is also the history of poetry in translation.

This is also a story of the history of friendship in poetry. I want to thank poet, translator, and critic Tiffany Troy for writing me about this chapbook, Todesfugue/Deathfugue.

A new letterpress chapbook from Orange Editions. Just 200 copies are available. https://smallorangejournal.com/orangeeditions

This is a very special chapbook which is devoted to just one poem. It is unlike any other chapbook I have seen because it contains the translation drafts in the translator’s own handwriting—showing how a poem moves from one language to another. Just as there is something thrilling about seeing Celan’s handwriting, there is also something deeply moving about seeing Celan’s translator’s handwriting.

These sorts of documents are usually only available in a university library; and in fact, all Joris’s other early versions are now archived at the Lilly Library of Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana.

But by chance, Joris came across one last collection of handwritten drafts. He explains in his introduction how he found a sheaf of papers he had forgotten about.

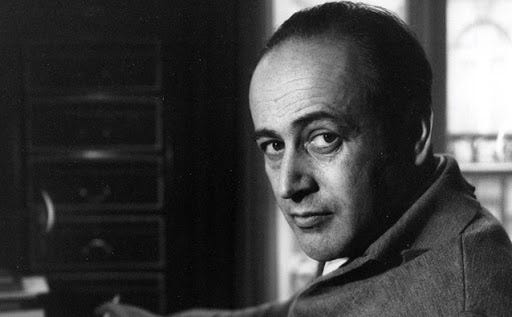

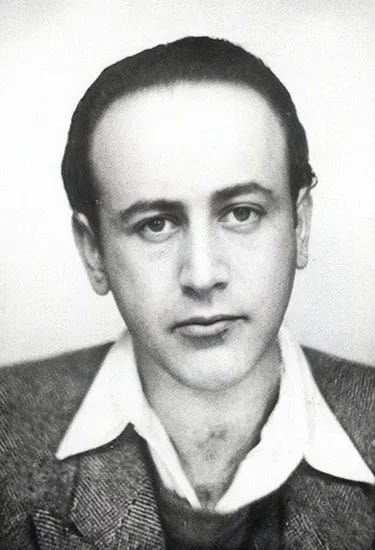

Translator Pierre Joris.

“I learned that an old friend, the Luxembourg poet Anise Koltz, had passed that very day, & I was asked by a friend to write an obit for Anise. As I set about to do this, I went to my bookshelves & pulled out an early 1960s anthology of post-war German poetry, knowing that the first poems by Koltz I had read were in that book. Opening this old paperback something fell out: a page from an old school-notebook on which I had handwritten a translation of… yes, “Todesfuge.” I had absolutely no memory of having done this, which must also have been my very first translation into English and must date from 1964 or 1965,” Joris writes.

And so, something wonderful this chapbook shows us a leading translator’s evolution over time. Amazingly, Joris writes that this particular Celan poem was the very first translation he ever attempted, in 1964 or 1965. It brought him into a life in poetry—and it so happened that that poem was Celan’s most famous poem is called Todesfugue in German, and “Deathfugue” in English. Its unforgettable opening lines, translated here by Pierre Joris, read:

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

Before going further, I recommend taking a few minutes to listen to Celan himself read this poem out loud in German. Even if you don’t understand a word of German, the experience of listening is powerful; here is Celan, on YouTube.

*

A Translator’s First Encounter with Celan’s Poetry

Joris first encountered this poem in high school, when his German-language teacher brought in a “peripatetic” actor to read Celan’s poem out loud. (It’s possible that listening to Celan is as close as we can get to this experience.)

“The poem went through me like a knife through butter, cut me open, laid me out, flayed. It may have been the one absolute epiphany I have experienced,” Joris writes in his beautiful introduction. “Reflecting on this experience over the years, I came to the conclusion that it was neither the beauty of the music, of the poem’s melodic fugal construction by itself, nor the obvious horror of the content — the exterminated bodies of the Jews going up in smoke to be buried in the air — that created this effect. No, it was the abyss opened by the paradoxical combination of those two elements into which I fell, it was the contradictory doubleness of that chiasmus that tore me apart.”

It’s clear that Joris has been thinking about Celan—and how to translate Celan—for decades. And that feels fitting, as Celan, too, thought deeply about translation, and translated many writers.

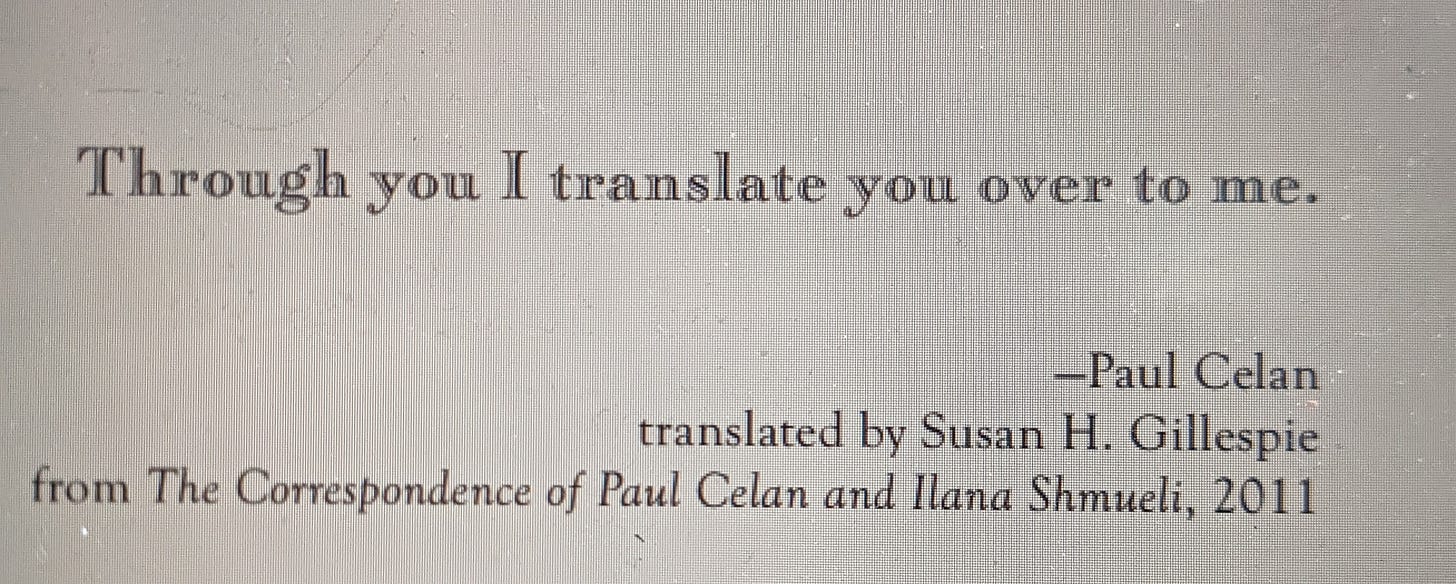

The epugraph to this chapbook.

A History of “Deathfugue”

Something that struck me this time, on this re-engagement with Celan, is just how young Celan was when he wrote this poem; he was born in 1920.

“Paul Celan completed “Todesfuge” at the latest in early 1945, and, more probably than not, in late 1944,” Joris writes in his introduction, titled “Notes on Todesfuge.” “This positions the poem squarely as one of the early “mature” poems of the young Celan, preceded only by the youthful poems — mainly love poems, though they already contain some of the darkness that became his hallmark. When he published it for the first time in 1947 in a Rumanian magazine and in Rumanian translation, the poem was still called “Tangoul mortii / Death Tango.”

“When he gathered it in his first volume, Der Sand aus den Urnen, in 1948, it appeared as the closing poem of that book — clearly a gesture to mark its special space, though not its chronological situation.”

In 1944, when Celan wrote “Todesfugue” / Deathfugue, he was just 24 years old.

Interestingly, Joris did not have a memory of translating this most famous poem. He recounts how he used Jerome Rothenberg’s translation of Celan in an anthology he edited. And one of the many intriguing “secrets” revealed by this chapbook is how the title of this poem in English changed over time in Joris’s process.

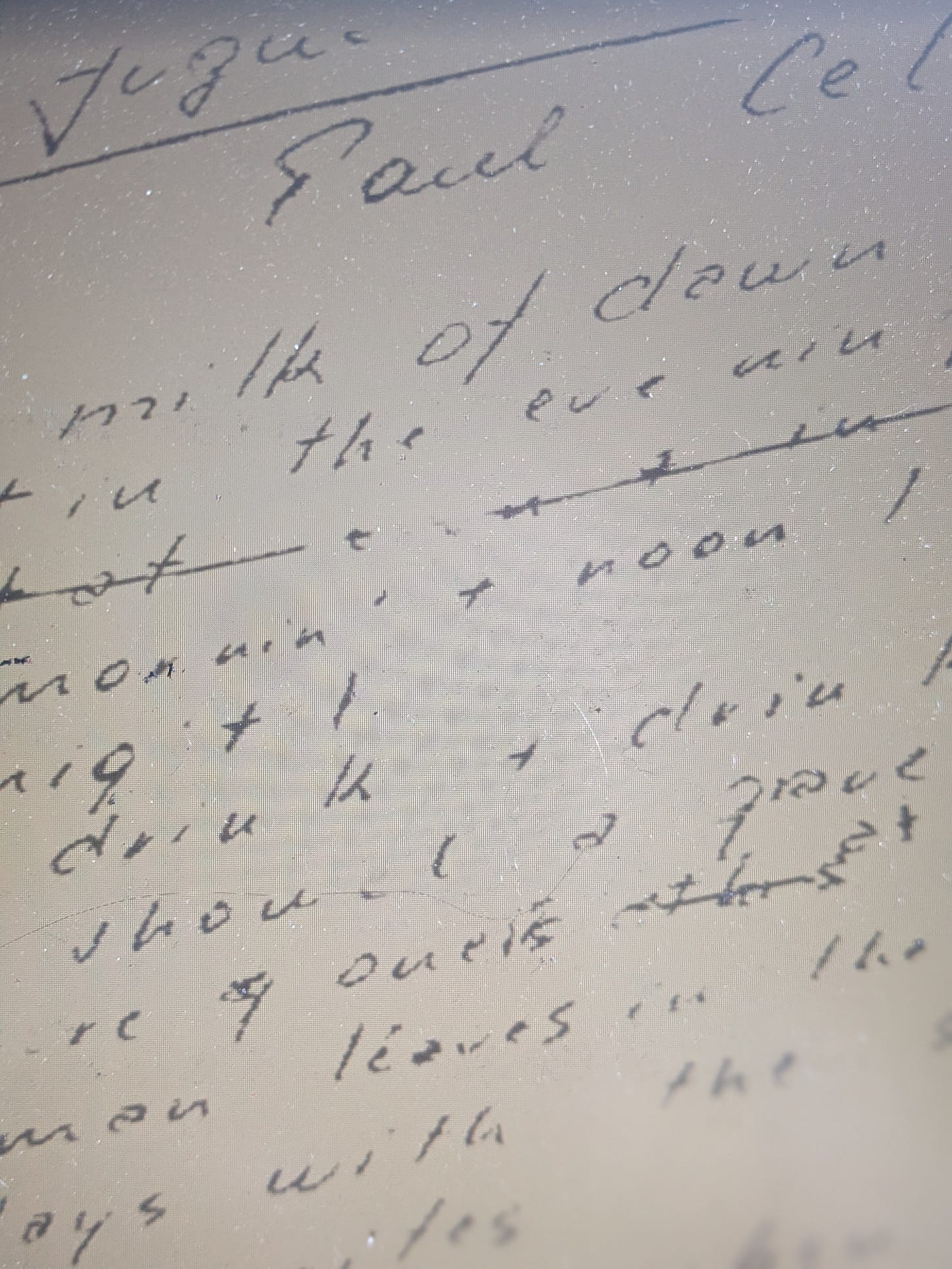

Take a look at the top line of the following drafts, to see the title transform.

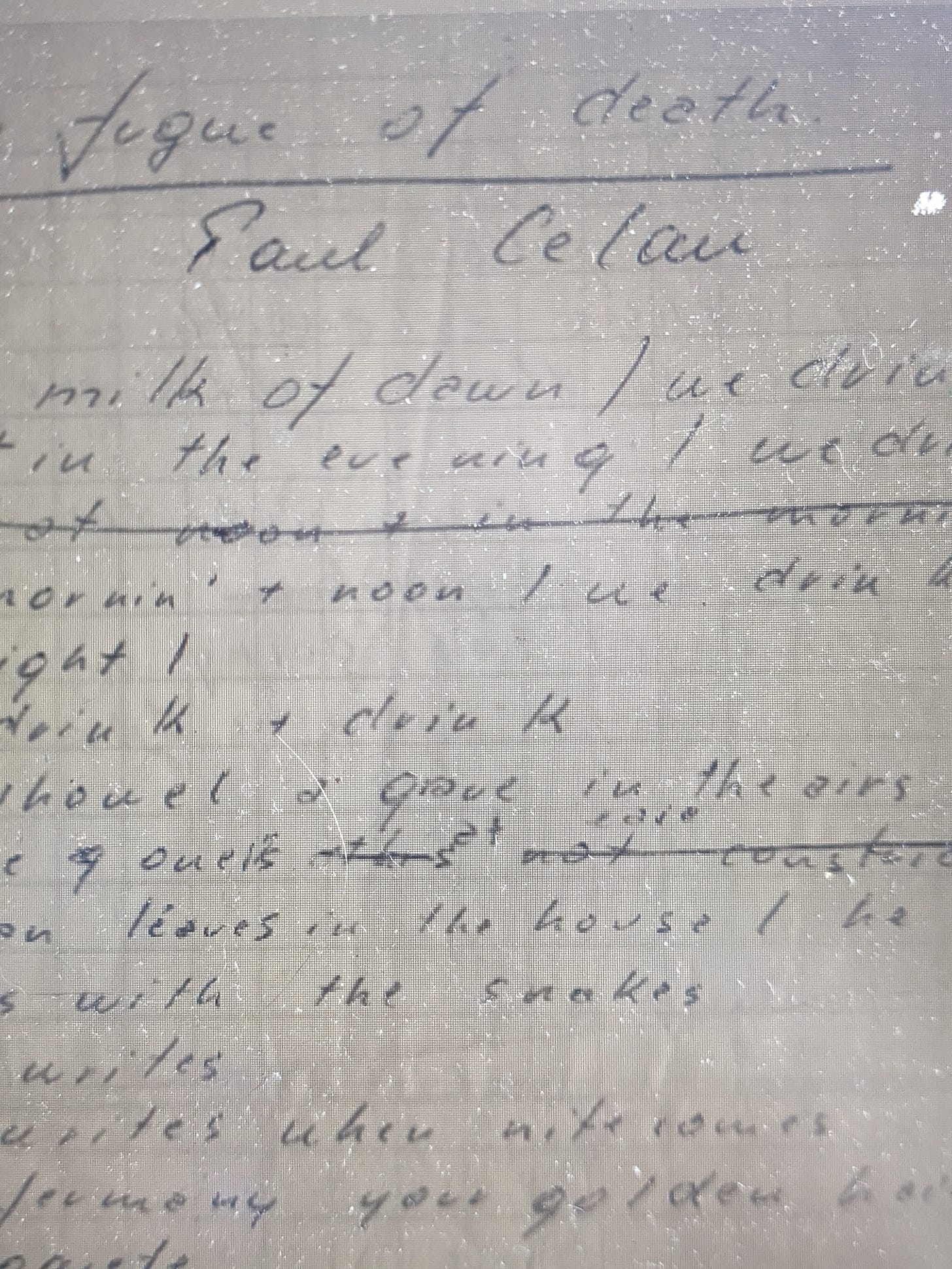

Translators sometimes change titles; here, the handwriting in Joris’s first, early, versions, shows a first title “Fugue” and then “Fugue of Death”.

A very early draft of Pierre Joris’s translation of “Deathfugue”. You can see that here, it is titled '“Fugue.”

In this draft, you can also see how “dawn” in the first line eventually became “morning”.

In another early draft, the title is now “Fugue of Death”.

Joris also shows how translators sometimes come across information that helps in the understanding of a poem. In this chapbook, he recounts how he was sure that the German word “Eisen” referred to a rod to hit someone with. Only later, after the big book of Celan translations was already in production, did he learn that “Eisen” was an abbreviation for a type of revolver.

Celan’s Relationship With His Most Famous Poem

Celan, for the uninitiated, had a troubled relationship with “Todesfuge” or “Deathfugue”. Then as now, there was a movement to minimize the Holocaust. And then as now, plagiarism accusations were making headlines and destroying reputations. Consider these astonishing sentences in Joris’s introduction:

“We know Celan’s later uneasy relationship to this poem: throughout the sixties he refused to have “Todesfugue” anthologized any further or to read it publicly. There are several reasons for this refusal: the most obvious one is that this poem, through its very “success,” had become endangered — in Germany it had become a pawn in the so-called “Uberwältigung-Prozess,” i.e., proof of the Germans having supposedly “overcome” their Nazi past. “

Not only is Celan’s poetry eternal—but many of the facts of his biography seem to be sadly relevant to our time, as Holocaust denial and atrocity minimization rises again. Here, Joris shows how Celan’s harrowing portrayal of the facts of the Khurbn—or the destruction, as it is called in Yiddish—was viewed as “pure fantasy”.

Joris, to his credit, names names. “Thus, for example, did the poet and critic Hans Egon Holthusen — who, it turned out, had been an enthusiastic SS before the fall of the Third Reich — claim in his essay “Five Young German Poets” (published in the very highly regarded and influential magazine Der Merkur) that Celan’s poem “escapes the bloody horror chamber of history” to “rise to the ethereal domain of pure poetry,” via a “dreamy,” “surreal” and “transcendent” language. “

“In other words, the claim was that Celan’s recounting of the historical facts of Khurbn were pure fantasy & unconnected with historical reality. This negation of the actual content of the poem was not a singular aberrance and happened with regularity throughout the fifties and sixties.”

Imagine accusing a Holocaust survivor of imagining slaughter. Celan himself was at a labor camp during the war, and not a death camp; but the poem likely reflects what he heard from other survivors.

Then imagine accusing Paul Celan of plagiarism. Who but Celan could come up with a transcendent—an eternal—last line like “count me among the almonds”?

Paul Celan.

Yet the idea of Celan the Plagiarist took root in the German press—and unsurprisingly, it deeply hurt Celan and played a role in his multiple mental health crises.

“Claire Goll, the widow of poet Ivan Goll with whom Celan had been close in the late 40s when he arrived in Paris, falsely accused Celan of plagiarism, and, shockingly, a range of German newspapers and reviews uncritically accepted and spread those false accusations,” Joris writes.

This 32-page chpbook is a chance to re-engage with Celan and with the translation of his work. It’s also a window into the life Joris has led, shaped by his passion for poetry, translation, and always, Celan. It’s a letterpress edition with just 200 copies printed. https://smallorangejournal.com/orangeeditions/todesfugedeathfugue-pierre-joris-paul

Chapbook aficionados tend to move fast, so if you would like to own a letterpress version of the drafts of “Deathfugue,” it’s $25. I also recommend asking your library to order a copy. (And after writing about OCTOBER, Louise Glück’s beautiful sold-out chapbook, I must note that chapbooks can sell out.)

Winter Sunday Salon on Celan

This deep re-engagement with Celan made me want to speak with the translator and editor who made it possible, and so I am thrilled to announce that the newsletter’s next Winter Sunday salon will be with translator Pierre Joris and editor Carlie Hoffman on February 25th at 12 ET/ 1 CST on Zoom.

We will discuss Celan, Pierre Joris's life in translation, the story of this chapbook, and the story of Celan's relationship with "Deathfugue" as well as Pierre's relationship to it. Carlie Hoffman will also talk about her vision for the chapbook and the press. (Mazal tov to Carlie, who just won The National Jewish Book Award for Poetry!)

Winter Sunday salons are for paid subscribers of On Being and Timelessness, in gratitude for their support. I do hope you will join us for this one-of-a-kind conversation.

And if you want to read more on Celan, I previously wrote about Celan’s letters to Nelly Sachs here: https://aviyakushner.substack.com/p/a-cure-for-writers-block-in-celans

Chapbook Panel & Chicago Reading

This post is part of a series of posts on chapbooks in advance of the AWP conference in Kansas City, where I will be moderating a panel on “Breaking the Rules on Chapbooks: New Approaches to an Old Form”. If you’re at AWP, do join us Friday, February 9, 2024 from 10:35 a.m. – 11:50 a.m. CT in Room 2101, Kansas City Convention Center, Street Level. I’ll also be signing books (and a chapbook) at the Yetzirah Poets table on Thursday from 3-4.

I will be reading with Peter Orner, one of the writers I most admire, on February 11th at 2 at the Chicago Loop Synagogue in Chicago. Our conversation will be titled: “Writing and the Art of Remembering: A Reading and Conversation with Writers Peter Orner and Aviya Kushner”. I will briefly recommend two of my favorite Peter Orner books—his debut, Esther Stories, and his sublime essay collection, Am I Alone Here?

Hope to see you online or in person soon! And as always, thank you for reading.

****************************************************************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

Thanks, Aviya! & Looking forward to the Sunday Salon!