In this time of fear, I am grateful for Jewish poetry. I am returning to the Psalms, and to poets wrestling with the Psalms. I keep re-reading one of my favorite phrases, from Psalm 69:5—rabu mi’saarot roshi son’ai chinam—or “those who hate me for no reason are greater in number than the hairs on my head.” Or, as the widely used Jewish Publication Society translation of 1985 puts it: “More numerous than the hairs of my head/ are those who hate me without reason.”

In all the loudness of the headlines, and the loudness of fear, I am finding that I am drawn to poets who convey quiet on the page. One of my favorite living poets is Jennifer Barber, known to all as Jenny. She was the longtime editor of Salamander magazine and is the author of four exquisite collections; she lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.

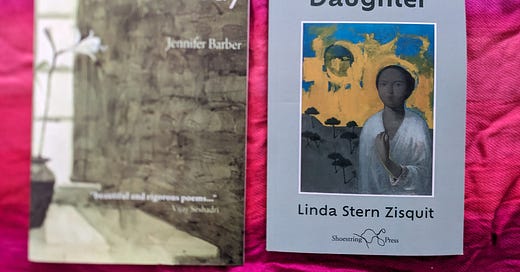

I want to highlight two of Jenny’s poems, both of which deal with flame—and their relatives, smoke and fire, along with two poems by Linda Stern Zisquit, whose recent work riffs off of the Psalms.

Making a Matchbox Into Poetry

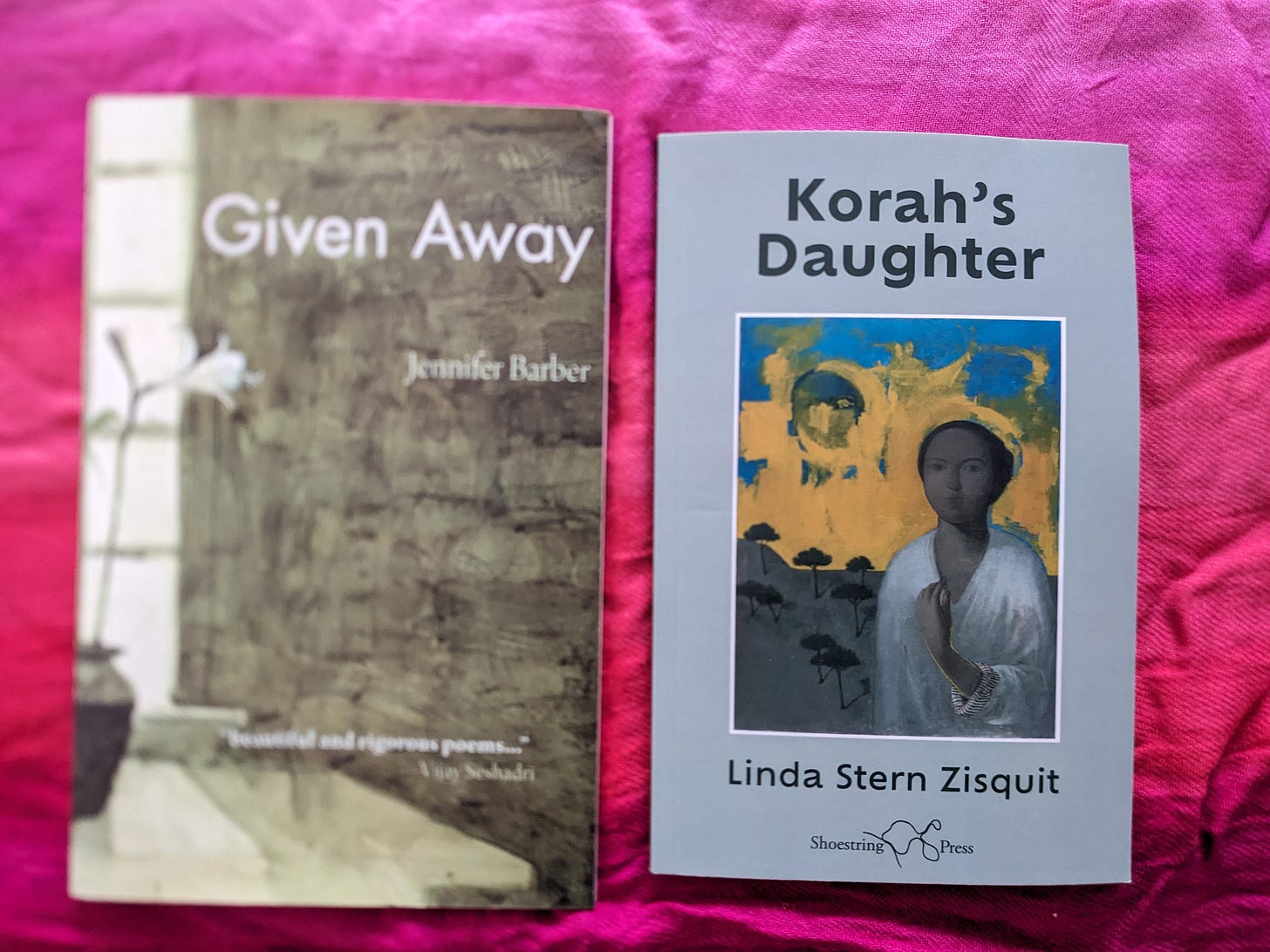

Only Jenny Barber could make a poem out of the common matchbox, with its 250 matches. Many of us cooking for Thanksgiving today are lighting a match, for a flame or a candle, preparing for guests and a kind of public space in our home. This is, for many of us, a year like no other, and our private thoughts may be far from what is on the menu.

The poem “250 Wooden Matches” begins with a closing of a door, and brings the reader into the poet’s private space. It delineates how fear and despair can mark us, but also, how we can still find a way to feel okay—we can find “a mood, a frame/ of mind to get through.”

Barber is a master of line-break and stanza break. Here, I love the stanza break between “hand” and “shaking”. I return again and again to “a fingerprint despair / intends to make on me.” Everything depends on that “intends”:

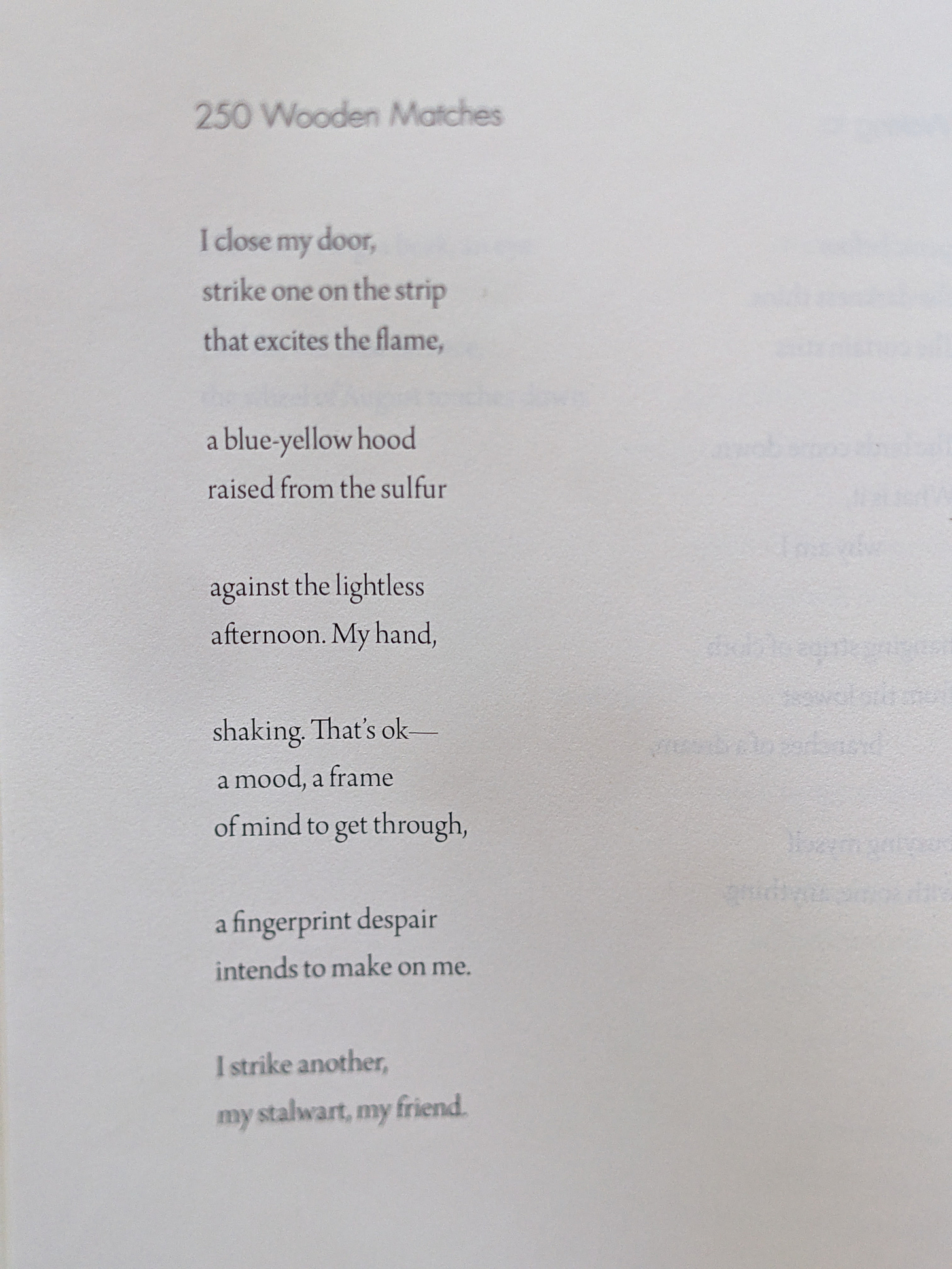

Jenny Barber’s poems can be both delicate and strong, and I love reading many of them, together. Barber’s poem “Scroll” feels to me like a prayer for this moment, even though the collection it appears in, Given Away, appeared in 2012. “In our fear,/ we are a shadow / on the grass” is so gently powerful. And somehow, the word “shadow” here reminds me of the Yom Kippur prayers, with the refrain of “man is like a passing shadow”.

Photo of Jennifer Barber by Joanna Eldredge Morrissey, 2017.

Reading Linda Zisquit’s Poems from Jerusalem

Jerusalem is home to many wonderful poets, writing in Hebrew, Arabic, English, Russian, Yiddish, and Amharic. The National Library of Israel, located in Jerusalem, runs a terrific poetry incubator program for poets writing in Hebrew and Arabic, who then translate each other. I often wish it would expand to other languages.

Linda Zisquit is the author of six poetry collections in English, and the translator of three volumes of Hebrew poetry into English. Born in Buffalo, NY, she has lived in Israel since 1978, where she runs Artspace, a gallery in Jerusalem representing local artists; I have been lucky enough to visit it. She also taught for many years at Bar Ilan University.

The first poem in Zisquit’s latest collection, Korah’s Daughter, is about a child’s survival. With children as Hamas hostages, the youngest just three, and news reports of more and more Gazan children killed in this war, the poem about the life of a child seemed apt. “I wish I wish there were some way to step outside time,” Zisquit writes, in one of the poem’s haunting lines.

Photo credit: Avigayil Schimmel

“In 2014 one of our children was diagnosed with cancer,” Zisquit writes for the Yetzirah Poets website. “Until that time my lucky life was interrupted only by the deaths of my beloved parents and occasional skirmishes with hidden desire. The psalms were no more than a familiar comfort I had read at difficult moments but when our daughter’s surgeon delivered troubling news, as war raged in Israel and the Palestinian territories, I found myself opening the Book of Psalms and started writing, choosing a line from the first psalm and free associating to it. I continued every day that summer as if I had assigned myself a way through our daughter’s recovery. Daily, I engaged the sacred and the profane, weaving together strands of personal and national trauma, completing one hundred and fifty “psalmwork” poems over the next many months.”

This poem takes Psalm 2:1 as its title. It’s also relevant for this moment, and the tradition of returning to the Psalms in times of trouble feels more and more present as these difficult weeks pass. Here, in this poem, too, there are hints of fear and its relatives in the second line, especially in “scare off/ the light?”

But what really moved me are the last four words—“the fiction of wisdom”.

This is a time when so many forms of wisdom seem like fiction. And yet, I hope we will see a wisdom that is truly wisdom, from our leaders, and from ourselves. In the meantime, there is poetry, ancient to present, with its wisdom of song.

********************************************************

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I am so grateful to see this work, with which I've not been familiar. Recently discovered and joined Yetzirah Poets, though, and finding this work, and my own, to be my spiritual home, more accessible and comfortable than the liturgy itself.