Everyone has a favorite prayer—even those of us who don’t pray. My favorite prayer is four lines long, and it is in both the Rosh Hashanah and the Yom Kippur liturgy. To me it’s a writer’s prayer; it asks God for the ability to speak, to express oneself, to find words that have meanings.

I love finding it each year. Here it is, on the bottom of the page in the first image below.

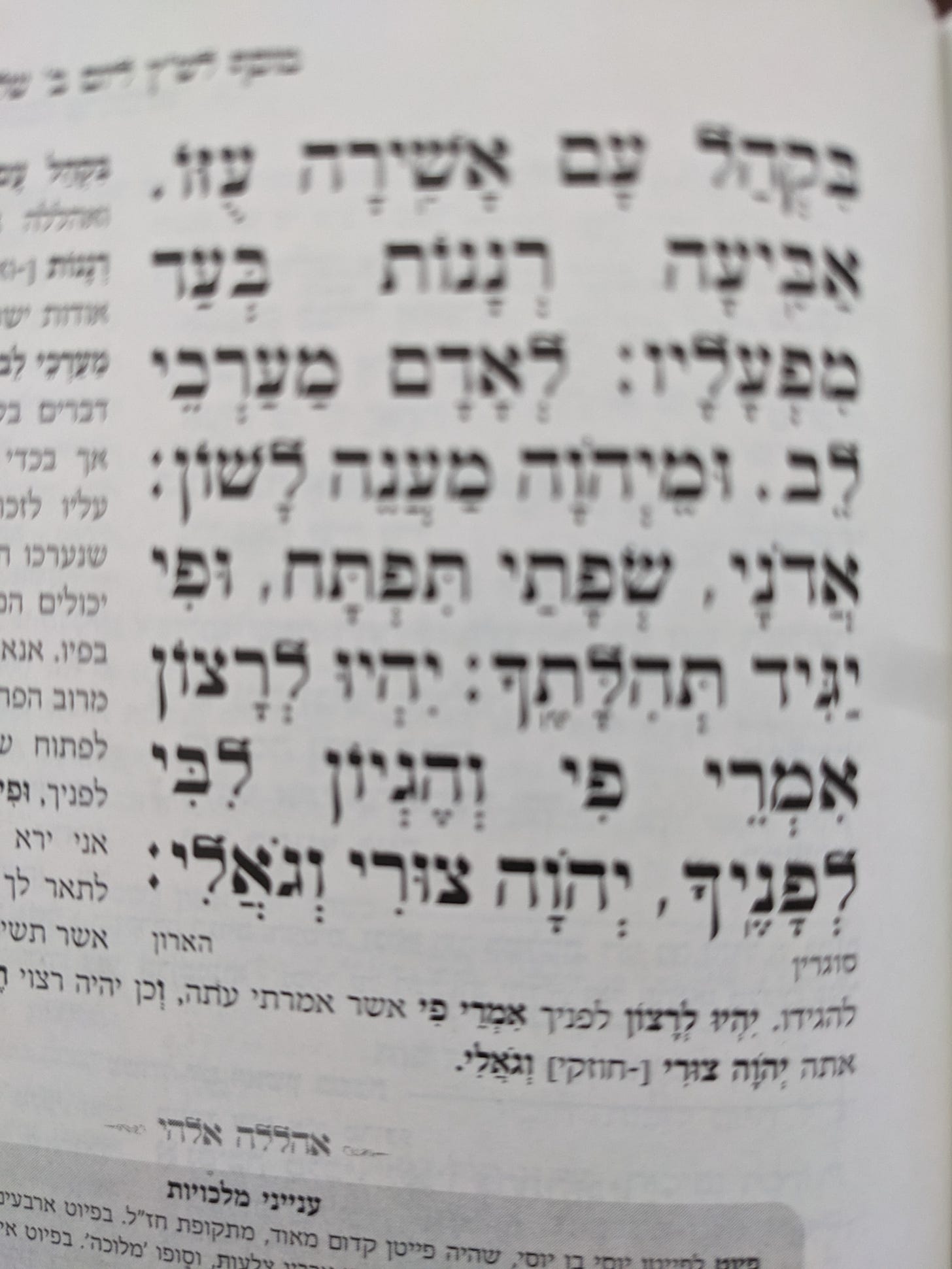

Even if you don’t read Hebrew you can see how the same letter—lamed—with its swirl upward and to the right, defines the first three words of the poem and gives it its music.

Ochila La’el appears at the bottom of the page. The last three bolded lines.

The rest of the poem, in bolded letters. Each verse ending is represented by a colon.

The problem with trying to translate אוחילה לאל --“Ochila la’el” -- is that what is beautiful about it in Hebrew is how it sounds—all those “l” sounds, those lamed sounds, in a row, threading throughout four lines. It is a poem that is sung, and it’s hard to separate the sound and the meaning.

But I think there are two solutions to this problem. And just so all of this is easier to follow, here it is in Hebrew, typed out. (Yes, this is a bilingual edition of the newsletter!):

אוֹחִילָה לָאֵל אֲחַלֶּה פָנָיו

אֶשְׁאֲלָה מִמֶּנּוּ מַעֲנֵה לָשׁוֹן

אֲשֶׁר בִּקְהַל עָם אָשִׁיר עֻזּוֹ

אַבִּיעָה רְנָנוֹת בְּעַד מִפְעָלָיו

Borrowing From the Rest of the Bible

First, this piyyut, like so many others, is constructed from quotations from other parts of the Torah, Neviim, and Ketuvim—from the Five Books of Moses, the Prophets, and the Writings. So it is possible to get a sense of its flavor by looking up multiple translations of the lines from the Proverbs, for instance, that the unknown poet—we don’t know his name—used.

For example, one verse in this prayer, which I especially love, is a complete lift from Proverbs 16: 1. Here is that verse in The Jewish Publication Society translation from 1985, which is a widely used translation:

“A man may arrange his thoughts, But what he says depends on the LORD.”

One problem with that is that it omits the tongue, which in Hebrew is both a body part and another word for language. In Robert Alter’s recent translation, Proverbs 16:1 reads:

Man’s is the ordering of thought,

But from the LORD is the tongue’s pronouncing.

Ahah. Including the tongue is an old strategy, and I can’t imagine a reader not knowing that the tongue is part of the verse. The King James translates it this way:

The preparations of the heart in man, and the answer of the tongue, is from the LORD.

I confess—I love “answer of the tongue” because it captures the Hebrew ma’aneh lashon.

Translations—in Words and in Music

There are a growing number of singers who have recorded this prayer, this song, this gorgeousness. As Rosh Hashanah approaches, I have been listening to their interpretations. Even if you don’t understand a word of Hebrew poetry, you can understand the clear and plaintive request to God.

But first, here is a translation of Ochila La’El from Rabbi Jonathan Sacks z”l, who was a beautiful writer, and who completed a translation of the entire High Holiday liturgy shortly before his death. In all honesty, I don’t know how I feel about the “shall” that Rabbi Sacks goes with. To me, this prayer feels more intimate. And the lineation here makes it feel longer than it does in Hebrew, but then, English is always longer than the Hebrew original.

I shall await the LORD, I shall entreat his favor,

I shall ask Him to grant my tongue eloquence.

In the midst of the congregated nation I shall sing of His strength;

I shall burst out in joyous melodies for his works.

The thoughts in man's heart are his to arrange,

but the tongue's eloquence comes from the Lord.

O LORD, open my lips, so that my mouth may declare Your praise

Further reading: For those who read Hebrew, the Wikipedia page for the prayer in Hebrew is pretty useful. https://he.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%90%D7%95%D7%97%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%94_%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%9C

And for those with some Hebrew, or a desire for commentary, Sefaria has a nice study sheet on Ochila La’El by Yaakov Ellis, which can help readers identify the sources of lines and find what the commentators had to say about those verses. I recommend it. https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/78972.7?lang=bi&with=all&lang2=en

Fascinating Recordings of the Prayer

Recently, Israeli singer Ishay Ribo sold out Madison Square Garden. He is a religious man, an Orthodox singer, and here is his rendition of Ochila La’el. You’ll notice that he doesn’t pronounce the name of God, though he would if he were actually praying in synagogue.

I found some of Ribo’s other pronunciation choices surprising. Usually, the word for “His face”—panav—is pronounced as phanav in this prayer, without the dot. (You can see it in the machzor images above.) But here Ribo goes with panav. To me, it was a bit jarring.

But this is a very relatable version, and it captures that essential sense of one person talking to God. Here is Ishay Ribo:

Another version I found of Ochila La’el has the more traditional phanav. It’s not as slick as Ishay Ribo, but it’s still interesting to listen to and it is deeply hearfelt, and it sounds like prayer. Like Ribo, these singers also do not pronounce the name of God, so it’s la-kel or “to God” instead of la-el, which also means “to God.” The singers are Yitzchak Meir and Uri Davidi, and the melody was composed by Rabbi Hillel Palei.

A third version felt the most Yiddish-inflected to me, and the closest to what I might hear from the Chassidishe neighbors in Monsey, where I grew up and where I will be for the holiday. It’s by Gilad Potolsky & Shalhevet Orchestra

But the version that most spoke to me was sung by a woman. I was surprised to find this—a religious woman singing. When I was growing up, I was not allowed to sing a solo in the choir because of the prohibition on a woman’s voice. And in synagogue, the only women singing out loud were always my mother and me.

Yifat Lerner’s Ohchila La’El showcases the beauty of a woman’s voice. Lerner is a nurse at a high-risk maternity unit in Israel; she is married and has three children. She is from a Moroccan family, and her father is a poet-singer. If you read Hebrew, you can read this article about her: https://www.inn.co.il/news/577106

Of all the recent recordings of this prayer, Yifat Lerner’s is my favorite. It sounds the closest to actual prayer.

My Favorite Way to Read This Prayer

As for me, my favorite way to encounter this poem is in one of the machzorim, or holiday prayer books, that my grandfather bought. Because he grew up in a Chassidic family, he used the Sephardi machzor. I also like hearing it sung by the chazzan, or cantor, in the synagogue I grew up in; he covers his head with a tallit, and I can say that I have never seen his face, but I know his voice in my bones.

The Rosh Hashanah chazzan’s mother was the assistant kindergarten teacher when I was in kindergarten. He moved away decades ago, but comes home each year, just for the chagim, to be the chazzan. He sings this poem with a certain amount of desperation, as if he is asking God for the ability to speak for the entire congregation. After the first line, he sings aaah-aaah-aah-AAAH-aah.

I should say that this chazzan---he is a lay person who just does this for a few days a year—has the most gorgeous rendition of hineni mi’maas, the chazzan’s prayer which begins the repetition of Mussaf. The most powerful part of it is how he uses silence. At the toughest parts, he is simply completely quiet.

My mother once spoke to him, and he said that he learned all his melodies from a very old chazzan who came from Europe. At the time, he was a teenager, and the old chazzan wanted his melodies to live.

The beauty of the old chazzan’s melodies is that a listener can understand every word. The emotion and the meaning are perfectly matched. During the pandemic, I found that I remembered all the liturgy for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, each and every melody that I grew up with. I think this is because of the old chazzan, and his then-teenage, now much older student, who has kept all his melodies going in this world. If I had to guess, the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur chazzan I have been listening to for my entire life is at least in his seventies now. But again, I have never seen him.

A machzor I purchased during the pandemic in Chicago, while missing my grandfather’s machzor.

After the experience of reading in my grandfather’s machzor while listening to the chazzan whose face I have never seen, my second-favorite is to read the commentaries by rabbis no one has heard of; every few years I buy another machzor with line-by-line commentary in Hebrew, and the effect is that I feel that the prayers are being introduced to me for the first time. During the pandemic, I bought extra machzors with energetic commentaries that no one else seems to have heard of from a little bookstore in Chicago. It is beautiful to know that there are new commentaries being written every year, and I recommend random machzor buying to everyone. Shana tova!

Hope you enjoyed this newsletter! Thank you for your support of writing with depth.

I too have been enjoying the many women's voices in prayer services now prevalent.

Thank you for this reflection and for compiling such a variety of versions. I too found Yifat Lerner's to be exquisite.